One thing stands out from the United Nations Climate Conference in Paris: Australia has proven itself a true world leader in blocking any serious, binding, action on climate change.

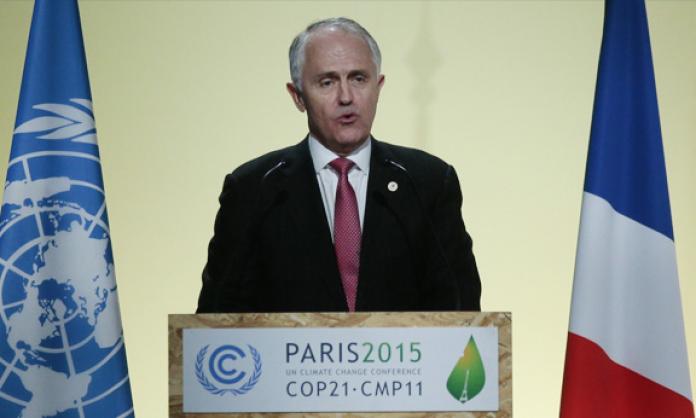

Whoever wrote Malcolm Turnbull’s speech for the conference should be given an award. Rarely has an empty void – the most accurate depiction of the government’s “commitment” to climate action – been dressed up into something appearing so earnest and substantial.

Australia, Turnbull announced, would ratify the second stage of the Kyoto Protocol – committing it to a 5 percent reduction in carbon emissions below 2000 levels by 2020. This is already a pathetic target, but behind the scenes Australian negotiators were lobbying hard to make it even more pathetic than it appears.

The point of contention was what could be counted as an emissions reduction. Australia’s achievement of a 5 percent reduction depends on the inclusion of a slowing in the rate of deforestation. You might think that a commitment to reduce emissions would involve, for example, things like planting more trees. But as far as the Australian government is concerned, it’s enough that we don’t chop down as many of them as we otherwise might.

Ever wondered what it means to do worse than nothing? In this area, Australia’s contribution to the world’s effort to tackle climate change is to continue to clear the land of forest, only at a slower rate.

The Australian negotiators’ furious efforts to forestall any attempt to close this loophole reflect its importance to the government’s climate policy. Researchers at the University of Melbourne found that, were a slowing in the rate of deforestation not counted as an emissions reduction, Australia would be on track for an 11 percent increase in emissions by 2020.

Another headline announcement in Turnbull’s speech was the allocation of an extra $800 million over five years to assist Pacific Island nations to deal with the impacts of climate change. In the small print, however, we find that the entire amount is to be redirected from the foreign aid budget.

So, for example, money that might previously have been spent on water sanitation projects in Papua New Guinea or the Solomon Islands will now be spent on “climate resilient” water sanitation projects. And given the almost $1 billion slated to be cut from the foreign aid budget in 2016, there will be a lot less of it than previously.

To be fair to the government, this could count as actually doing something about climate change. No doubt someone in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) spent a chunk of time making a new “climate funding” spreadsheet and transferring the numbers across from the sheet for foreign aid.

The third “big-ticket” item announced by Turnbull at the conference was a plan to double the government’s investment in clean energy research and development to around $200 million by 2020. At first glance this is all very commendable. But the $200 million pales in comparison to the more than $10 billion in subsidies that, according to an Environment Victoria analysis, the government gives to the fossil fuel industry each year.

This is a set-up that Turnbull and his diplomatic henchmen have proven themselves loath to give up on. Shortly before he strode onto the world stage to trumpet the values of clean energy innovation, he was on the phone with New Zealand government officials, informing them that Australia would not be signing on to a communique they had formulated on the phasing out of such subsidies.

Almost forty other countries signed on to the agreement – a small but important step. Meanwhile, in Australia, the likes of Gina Rinehart, Clive Palmer and other fossil fuel dinosaurs were rubbing their hands.

Australia’s role in Paris, of climate vandal in chief, should come as no surprise. Over the past few months there have been numerous indications of the government’s real agenda.

In October, environment minister Greg Hunt gave the final go-ahead to the construction of the Carmichael coal mine in Queensland. The mine will be Australia’s largest ever; once fully operational, it will produce more carbon pollution than New Zealand.

The government also signed off on the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a trade deal involving 12 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, which collectively produce more than 40 percent of global GDP. The deal is not a positive step for the environment. As 350.org policy director Jason Kowalski put it:

“The TPP is an act of climate denial. While the text is full of handouts to the fossil fuel industry, it doesn’t mention the words climate change once. The agreement would give fossil fuel companies the extraordinary ability to sue local governments that try and keep fossil fuels in the ground.”

In explaining the “benefits” of the agreement, the Australian government has singled out mining as a particular area of opportunity. According to DFAT, the TPP lays the basis for continued expansion of Australian coal and other fossil-fuel exports and creates “major new opportunities for Australian miners and oil and gas companies to find and develop reserves in the region”.

Malcolm Turnbull may present as a scientifically literate man of vision – a clear break from the dark days of Tony “coal is good for humanity” Abbott. But behind the carefully crafted rhetoric, it’s business as usual – throwing a bone to the popular sentiment for climate action, while fighting to protect the super-rich minority who profit from trashing the Earth.