The new UN agreement on climate change has been widely praised as a significant breakthrough in the effort to reduce carbon emissions and prevent catastrophic global warming. The adoption of the agreement at the conclusion of the UN climate conference in Paris was greeted by wild applause and “tears of joy” among the assembled delegates.

The response of major environment organisations has been similarly misty-eyed. The Nature Conservancy labelled the agreement “a historic moment” and “truly inspiring”. 350.org described it as “landmark” and “a signal … that the age of fossil fuels is over”. Similarly, the Australian Conservation Foundation said that it “signals the end of the fossil fuel age and will turbo charge the clean energy revolution already underway”.

The rhetoric

The text, negotiated and approved by all 196 countries in the world, certainly contains higher ambitions than previous agreements.

The agreement aims to limit warming to below 2 degrees Celsius – the scientifically-recognised “tipping point” beyond which catastrophic, runaway warming becomes more likely – and, if possible, keep it down to the 1.5 degrees that would give low-lying nations a fighting chance of not being swallowed by rising seas.

This goal is to be achieved via individual countries’ “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs) – voluntary pledges to reduce carbon emissions over the decade and a half to 2030. One hundred and eighty-five countries, contributing 94 percent of global emissions, have submitted their INDCs. The remaining countries are due to submit in the next year.

Under the agreement, these initial pledges will be subject to five-yearly review, with the first scheduled for 2018. Countries are expected to ramp up their commitments over time, with the aim of achieving zero net global emissions by 2050.

Finally, the agreement commits developed countries to establish a fund for assisting poorer nations to cope with the effects of climate change and to fund sustainable economic development. Starting from 2020, US$100 billion will be distributed annually, with the figure expected to increase over time.

The reality

If countries’ efforts to tackle global warming match the rhetoric of the agreement, then we could justifiably see the Paris conference as a turning point. Unfortunately, however, all signs point to this being just another case of fiddling while the world burns.

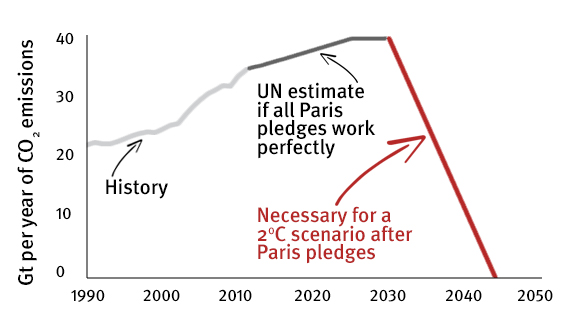

For a start, the 185 INDCs submitted are nowhere near sufficient to achieve the goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees. Even assuming that the pledges are actually kept (which, going on past experience and contemporary evidence is highly doubtful), the outcome, by 2030, would be an increase in global emissions to a record 40 gigatonnes (from around 36 gigatonnes today).

According to climate scientists, to have a reasonable chance of limiting warming to less than 2 degrees, the world has a “carbon budget” of just 1,000 gigatonnes from 2011. Were all pledges to be kept, approximately 723 gigatonnes of this would be used up by 2030. That would leave at most 14 more years for the world to reduce its emissions to zero – otherwise the carbon budget would be well and truly blown.

Given that the current, supposedly groundbreaking agreement will at best result in only a small slowdown in emissions growth, the idea that from 2030 we will be able to carry out such a sharp turn to deep emissions cuts is outlandish. By then, we will be living in a world even more reliant on fossil fuels than today. India, for example, plans to double coal output to 2020 and is expected to increase the proportion of its total energy supply produced from coal from 43 percent in 2014 to 51 percent by 2035.

According to the most optimistic assessments, the pledges made at the Paris conference put the world on course for an increase in average temperatures of 2.5 to 3 degrees. For the vast majority of humanity, that would be a disaster.

Sea-level rises will render entire countries uninhabitable. An increasing frequency of extreme weather events – heat waves, droughts, floods, cyclones and storms – will devastate lives and communities around the world. Reduced crop yields will drive the poorest to starvation and plunge millions more into extreme poverty.

SOURCE: climateparis.org

Not binding

The real kicker with the “inspiring” agreement is, however, that even the vastly inadequate pledges that have been made to date are, given the lack of any mechanism to seriously hold countries to account, likely to be turned into a dead-letter before long.

We need only look at the example of Australia to see how seriously governments are taking the “commitments” made in Paris. The Australian delegation, led by environment minister Greg Hunt, returned from the conference to the unanimous applause of the conservative press and the fossil fuel lobby.

Australia’s lack of ambition was made more or less explicit from the start. The government’s INDC commits us to “an economy-wide target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2030”. Sounds impressive – but shortly afterwards we come across the rather stark escape clause: “We will implement the 28 percent target should circumstances allow”.

By “circumstances”, we can only conclude that the government might mean things like the recently approved Carmichael coal mine in Queensland, a mine that once operational will be responsible for more carbon emissions than New Zealand. These are the kind of “facts on the ground” the Australian government will almost certainly use to reduce its commitment over time, rather than increase it as expected by the agreement.

No wonder that the Minerals Council of Australia has welcomed the Paris agreement as “an important step forward”. James Paterson from the extreme neoliberal, right wing think tank the Institute of Public Affairs put it most clearly in an interview with Sky News: “The truth is there is no legally binding mechanism to enforce the pledges that countries have made, and even the pledges that countries have made are going to go nowhere near what climate activists say we need … [and] that’s a good thing”.

What, then of the US$100 billion to help tackle climate change in poorer countries? The first thing to note is that it’s an absolute pittance compared to global subsidies for fossil fuels. As detailed in a recent report by the International Monetary Fund, incorporating the costs of environmental, health and other damages, alongside cash handouts to industry, these amount to US$5.3 trillion annually.

Second, even the US$100 billion is far from a firm commitment. As noted by John Vidal, writing in the Guardian, “The Paris agreement actually weakens the existing responsibility of rich countries to provide finance … Although the Kyoto agreement made it a legal responsibility for rich countries to help poor nations, that responsibility is now voluntary and shared between all countries”.

Greenwashing

The agreement was accurately and succinctly described by former NASA scientist and “father of climate change awareness” James Hansen as “a fraud … just worthless words”. In this context, attempts by some in the environment movement to present it as a significant breakthrough aren’t just delusional; they’re dangerous.

There’s nothing the fossil fuel industry would love more than to be given breathing space while the world waits in anticipation of a something that’s never going to materialise. While the likes of the ACF laud “the end of the fossil fuel age”, in reality the demand for cheap, dirty fuels like coal continues to rise at pace.

Capitalism isn’t run on wishful thinking. The heart and soul of the system is profit. While there’s still a buck (or, more accurately, trillions of bucks) to be made from digging up and burning fossil fuels, there will be no shortage of those willing to do it, and no shortage of governments willing to undertake the political and diplomatic contortions required to protect their interests.

To these people, the Paris agreement is no more than “worthless words”. The fate of island nations at risk of drowning under rising seas, or of the millions who face hunger and starvation in a warming world, matters not a jot. The immense wealth and power they stand to gain from continuing to trash the planet ensures that they will face few consequences.

Those who care about the future of the planet need more than words. We need a movement that can challenge the interests of the rich and powerful minority who own, operate and reap the lions’ share of the benefits from the fossil fuel dependent capitalist economy of today. The Paris agreement, far from giving us cause for any kind of celebration, only adds new urgency to this project.