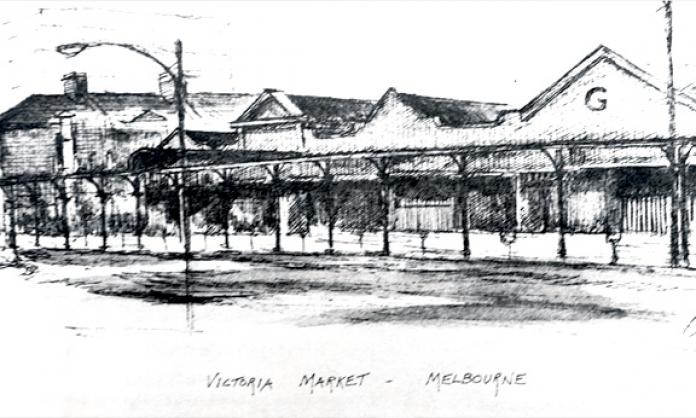

Melbourne’s iconic Queen Victoria Market is up for World Heritage listing. The city’s lord mayor, Liberal Party member Robert Doyle, is at the forefront of the campaign extolling the market’s virtues and its 138-year history.

What you won’t find anywhere in the lord mayor’s talking points is a word about the union that saved the market from the wreckers’ ball in the 1970s.

As a boy, Norm Gallagher had worked at the market and later, no longer on the tools, but secretary of the powerful Builders Labourers Federation, frequently shopped there. The stallholders and fellow shoppers knew him and knew the union, so when the council talked of closing down the market and turning the site into a hotel and office complex, they approached him for help.

The BLF stepped in, putting a ban on any demolition or redevelopment work. This, and the stallholders and community campaign, forced the council to back down.

“The union got its encouragement from the people. They, in turn, got encouragement from the union. So it was a team effort”, Norm said, later reflecting on the union’s green bans policy.

While the most famous of the union’s green bans were in NSW, the BLF’s first bans were in Victoria. Before 1970 there were a few, including the preservation of a park at Caulfield Tech, but the first notable ban was over abandoned railway land in North Carlton.

Local residents, campaigning to have the area developed as a public park, had already won a number of battles in 1969 and 1970 to retain public housing and restrict a school takeover. Then in 1970, they faced a developer wanting to build a warehouse in the middle of what was to be their parkland.

After their appeals, legal action and the like led nowhere, they turned to more direct action. One of their council supporters, Labor’s Fred Hardy, declared, “Opponents of this plan will use every means possible to see that this warehouse is never built – even if it means taking direct industrial action”.

More than 20 unions agreed to ban the development, but the builder was having none of it and started construction in late October using scab labour. By November, Norm Gallagher had been arrested and jailed for attempting to stop the work. It was then that the campaign took off. City building jobs were closed and protesters rallied outside Pentridge Prison calling on the state to “Free Norm”.

And they won! In early 1971, the developer withdrew from what he called “Carlton’s rubbish dump”, though it wasn’t until 1992 – and after many, many meetings – that the fully planned Hardy-Gallagher Park was established.

The union went on to save a number of significant sites around Australia. In Melbourne, among many, these include the City Baths, Regent and Princess Theatres and the Windsor Hotel. The bans also stopped the construction of a car park and all-night restaurant in the Botanic Gardens.

Writing about the politics of the bans, Gallagher said that the union wanted progress – the best of what is new – alongside preservation – the best of what is old. The protection of public and low-rent housing, the need for parks and open spaces, historic buildings, the needs of the community, were among the criteria the union used to assess each site.

Above all, there needed to be an active community group, prepared to fight for their cause, and it had to be the union members themselves voting for or against the bans. If they were going to win, “Mass struggle is the key word”, according to Norm.

The ruling class hated the green bans. They were incensed that workers dared to have an opinion on architecture, urban planning, aesthetics or history. When Justice Smithers deregistered the NSW BLF in 1974, he cited the green bans as a factor. “It is as though the [union] converts the expression ‘Have gun will travel’ to ‘Have power will ban’”, he said in his decision.

But it was through actions like these that the BLF earned its reputation as one of the country’s leading unions, the union that “dared to struggle, dared to win!”