Twenty-two years after the fall of apartheid, and South Africa is still a country highly polarised between the haves and have-nots.

I could cite the Gini coefficient, which measures inequality between rich and poor, which tells us that South Africa is in a hot contest with Brazil and China for the title of most unequal society in the world. I could point to the fact that the top South African bosses commonly earn 200 times the average wage of their employees.

But a better way to understand the sheer barbarism that is capitalism in South Africa is to take a simple 45-minute drive from Johannesburg to the township of Tembisa, which I did on May Day.

The freeway out of Johannesburg heading north to Tshwane (Pretoria) is a top-quality road lined on both sides by beautiful parks and grand houses. Twenty minutes out of town, the houses give way to expansive air-conditioned shopping malls, smart office parks and warehouses.

All the big international brands are here. Cranes dot the skylines. The cars on the road are late model and the drivers speed along unhindered at 120 kilometres an hour. Although the drivers are for the most part white, a minority are Black, some of the 4 million or so who have broken through the class barrier since the fall of apartheid. Their numbers have doubled in the past decade.

Turning off the freeway about half an hour short of Tshwane, you enter a different world. You’ve encountered the first “informal settlement”. Here you witness life as it is for millions of South Africans and migrants from elsewhere across the continent, living in shacks put together from corrugated iron sheets.

Now, the main means of transport is on foot along dusty, broken-up roads, with large pools of fetid water, uncollected garbage and piles of burning rubbish on each side. The air-conditioned malls are replaced by “spaza shops”, run out of people’s homes where people with a few rand try to make a go by selling cheap goods to their impoverished neighbours.

Further along, into Tembisa, the informal settlement gives way to the township proper. Here you may find a few privately-owned brick houses mortgaged to the banks, a KFC and a string of more modern-looking shops.

But these are outnumbered by the tiny four-room apartheid era “matchbox” houses – two bedrooms, one kitchen, one living room, shower and toilet outdoors – and the so-called RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme) houses, little more than tiny cabins, which have been built in large numbers since 1994. Try as you might, you won’t see more than one or two white faces in Tembisa, the region’s largest township.

On the drive back to Johannesburg we were stuck in traffic as the minibus taxis, packed tight with passengers and held together with gaffer tape and fencing wire, jostled for space on the road with pedestrians going home – little wonder that 100 pedestrians are killed each week on the roads of South Africa.

But alongside the narrow road was another road, half built, the beginning of an extra two lanes to aid the flow of traffic. This has been under construction for five years, testimony to the shocking waste and corruption caused by the ANC’s decision to outsource public construction of roads and houses to the private sector.

Outsourcing has been a gold mine for the new layer of grasping “tenderpreneurs”, sometimes beneficiaries of “black economic empowerment”, who grease the palms of ANC politicians to win the contract knowing that they can recoup the money once the paperwork has been signed. As for the road itself, well that can wait until they’ve spent the money.

None of this is new. Anyone with eyes to see has noticed for years the slow progress to end the yawning gap inherited from apartheid. The 1994 settlement has brought emancipation to a few. But for the majority of Blacks, not much has changed – 10 million live in extreme poverty and household incomes are one-sixth of those of whites.

And with the economy staggering under the impact of the mining bust, hundreds of thousands of workers are threatened with retrenchment, adding to the millions already unemployed. Meanwhile, those who dominate ownership and control of the big mining companies, banks and industrial corporations remain lily-white for the most part.

What is new, however, is that things are stirring politically. The ANC government is deeply factionalised, with two wings at war with each other over the spoils of office. Divisions at the top are creating space for movement below.

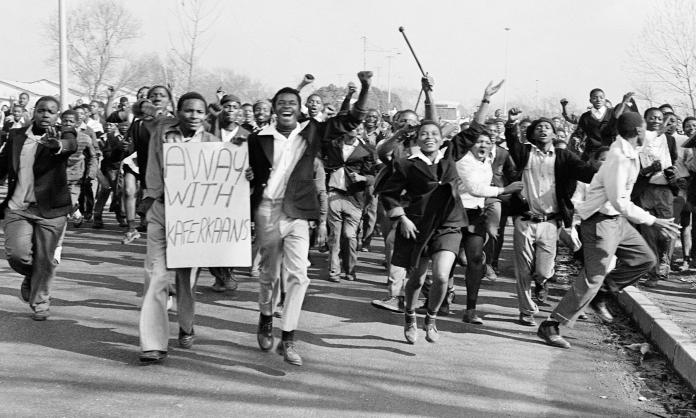

The police shooting dead 34 striking platinum miners at Marikana in August 2012, on the orders of senior figures in the ANC government, marked the start of a new period in South African politics. Unions are breaking from the grip of the ANC.

On the campuses, there is every reason to expect that last year’s wave of student protest will not be the last. In a context where the results of majority rule have fallen far short of the high hopes of 1994, workers and students are now getting back on their feet, organising and demanding their rights.