The latest opinion polls show record levels of support for minor parties and independent candidates – almost 30 per cent in the House of Representatives and undoubtedly considerably more in the Senate. This is but one reflection of the widespread disillusionment with both major parties, most notably with the ALP, whose primary vote stagnates in the low 30s.

Labor still has a chance of winning the elections, but that more reflects anti-Liberal sentiment and growing cynicism about Turnbull than a positive endorsement of Labor. Despite running a relatively left wing campaign, Bill Shorten has been unable to inspire enthusiastic crowds of workers and young people in the way Jeremy Corbyn has in Britain or Bernie Sanders has in the US.

None of this should come as any great surprise. A few pro-worker promises – opposition to company tax cuts, rolling back of negative gearing, defence of Medicare and so on – were never likely to be sufficient to overcome the legacy of 40 years of Labor cosying up to the big end of town and screwing over its working class supporters.

Labor has never been a genuinely socialist party. Throughout its 125-year history, it has always played by the rules of the capitalist game in an attempt to stay on side with the rich and powerful who dominate the Australian economy.

At times, Labor has legislated reforms. But they were in response to mass upheavals from below that forced concessions from the ruling class or in periods of sustained economic expansion and booming profits, when the bosses were prepared to hand out a few crumbs to maintain social peace.

However, when the economy faltered and profits were under pressure, Labor proved its loyalty to the ruling class by disciplining its working class supporters to accept sacrifices in the supposed national interest.

This was graphically illustrated in the case of the Whitlam government – the last genuinely reforming ALP government. Whitlam came to office in December 1972 at the tail end of the long postwar economic boom.

An increasingly confident working class was demanding its share of prosperity. Militant workplace-based shop steward networks forced individual employers to grant higher wages and improved conditions.

In 1969, a general strike smashed the anti-union penal powers and forced the release of jailed Tramways Union secretary Clarrie O’Shea. In the aftermath, strike levels skyrocketed. This massive upsurge in working class struggle intersected with and reinforced the worldwide political radicalisation centred on opposition to the Vietnam War. The university campuses were rocked by wave after wave of occupations and confrontational protests.

For the previous two decades, the press had denounced Labor as being in bed with the communists. But in the face of this mass radicalisation, some sections of the ruling class, notably including Rupert Murdoch, began to view favourably the prospect of a Labor government.

They hoped that Labor, under Whitlam’s reliably moderate middle class leadership, would be able to blunt working class militancy by granting some long overdue reforms and coopt sections of the radical left and the array of protest movements that had sprung up in the late 1960s.

Considerable numbers of one time student radicals did fall into line behind Whitlam as some of the heat went out of street protests with the withdrawal of Australian troops from Vietnam. Labor was also highly successful in coopting leading figures from the women’s, migrant and environmental movements via a series of token measures and a swathe of bureaucratic appointments.

It was an entirely different matter when it came to the workers’ movement. There was no ebb on the strike front. Indeed, workers surged forward with explosive outbreaks such as the 1973 riot and nine-week strike at Ford’s Broadmeadows factory in defiance of union leaders.

By 1974, strike levels were double what they had been before Whitlam came to office, and workers were winning major wage rises. The ruling class became increasingly uneasy. Their fears were compounded by the onset of a recession in mid-1974, which heralded the end of the postwar boom.

Sensing that the good times were over, the bosses jagged sharply to the right and turned on the Whitlam government. They demanded cutback after cutback. It was the beginning of the neoliberal age of austerity.

Whitlam fell into line. Workers striking for higher wages were stridently denounced. “One man’s pay rise is another man’s job” was the new Labor mantra. “Unreliable” left wing ministers like Jim Cairns and Clyde Cameron were sacked, and a new treasurer, Bill Hayden, was installed with the sole mission of taking a knife to government spending.

However, it was not enough to satisfy the howling wolves of the big end of town. They rallied behind new Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser in preparation for a frontal assault on all the gains workers had made over the previous decade.

The press unleashed a no-holds-barred campaign against the Labor government, preparing the ground for governor-general John Kerr to launch a coup to remove Whitlam from office and install Fraser as prime minister. Even the pretence of democracy was trampled underfoot in defence of the “greater good” – corporate profits.

Workers were outraged. As word of the coup spread, workers immediately walked off the job. Militant protests took over the streets. Liberal Party headquarters in Melbourne was stoned, and Murdoch’s offices in Sydney were besieged and his papers burnt.

Rank and file pressure was building up for a general strike. In Melbourne the leaders of the left unions were forced to call a one day stoppage. But the old reliables, the top trade union officials, rushed to the rescue of the ruling class.

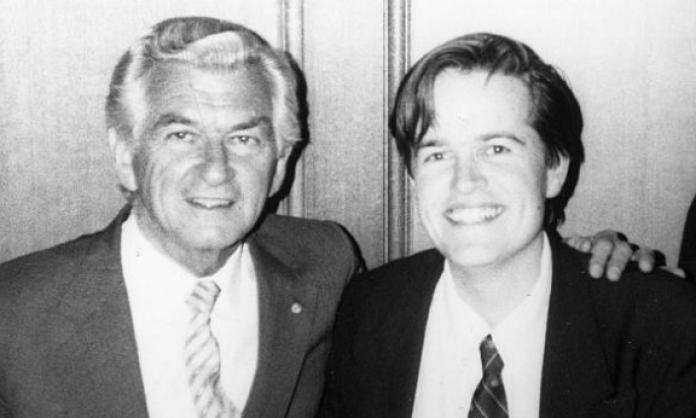

Bob Hawke, who was then ACTU secretary, used all his influence to limit strike action. He was backed by Whitlam, who called on workers to “maintain your rage” – but only by voting. The left officials, such as communists John Halfpenny and Laurie Carmichael, had a strong following among militant shop stewards. They were key to containing the situation.

Once the strikes against the Kerr coup had petered out, the ruling class was able to go back on the offensive, and Fraser triumphed at the election.

But it was a reviled Fraser government that took office. In the face of dogged working class resistance, it was incapable of ticking all the boxes on the ruling class’ wish list. Indeed, a mining boom at the end of the 1970s enabled workers to win important wage gains via renewed strike action.

Meanwhile, the marked shift to the right by the ALP had been consolidated. The conclusion that the Labor left and right drew from the experience of the Whitlam years was that they had gone “too far too fast”. Even moderate Keynesian-style reforms were now entirely off the table. We all had to learn to live within our means. Cutbacks and sacrifice were to be the unanimous message of both Labor and the Liberals.

This sharp swing to the right was not confined to the ALP leadership. Both left and right wing union officials fell into line, as did the Communist Party and much of the broader left. Reactionary ideas triumphed across the board. The once radical street movements retreated and turned in on themselves; on the campuses, the scene was set for the rise of obscurantist fads like post-modernism.

In the unions, the Communists and Labor left officials in previously militant unions like the metalworkers led the charge to the right. They drew up plans for a Prices and Incomes Accord between the unions and a future Labor government.

By 1983, the ruling class was prepared to give the Accord the green light. Fraser had singularly failed to break the back of the unions and push down wages. So Labor, now under the leadership of Bob Hawke, was to be handed the baton.

From the ruling class’ standpoint, the Accord was spectacularly successful. Under the Hawke/Keating government in the 1980s, Australian workers suffered their greatest ever reduction in real wages.

The ACTU leaders acted as a police force for the Labor government, rigorously disciplining workers who stood up for their rights and smashing unions like the Builders Labourers Federation and the Australian Federation of Air Pilots that defied the Accord.

All of that was bad enough – but it wasn’t simply that the Accord cut wages and savaged working conditions. It also sharply undermined workplace-based union organisation and set the scene for the subsequent collapse in strike action and union membership.

The Hawke/Keating governments were not content with forcing down wages and destroying union organisation. They forced through a wave of privatisations of everything from the Commonwealth Bank to Qantas, rolled back key reforms of the Whitlam era such as free university education, enthusiastically backed George H.W. Bush’s 1991 war on Iraq and introduced mandatory detention for refugees. This set the pattern for every subsequent Labor state and federal government.

Labor’s betrayals and demobilisation of its working class supporters laid the basis for subsequent Liberal governments to go further on the attack. Hawke and Keating prepared the ground for the horrid Howard years. In Victoria, Joan Kirner’s ALP Socialist Left government softened workers up for a brutal onslaught by Jeff Kennett in the early 1990s.

By 2007, the absolute pits had been reached with Kevin Rudd boasting his “economic conservative” credentials. The Rudd/Gillard years were sorry ones indeed, with the supposedly left wing Julia Gillard competing with Tony Abbott in a relentless race to the bottom to prove who could be the most brutal to refugees, opposing even basic reforms like same sex marriage and cutting university funding. No wonder Labor can’t inspire enthusiasm.

In an attempt to shore up support in its disillusioned working class voting base, Labor’s rhetoric has shifted to the left in this election campaign. Shorten and Co. have also sensed the leftish mood internationally with the growth in support for Corbyn, Sanders, Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain.

But left rhetoric is cheap. The capitalist class clearly recognise this. They are not alarmed at the prospect of a Shorten government.

Sure, they would prefer to see Malcolm Turnbull triumph on 2 July. However, if Labor manages to scrape over the line, the business establishment know full well that their fundamental interests will not be threatened. Labor has a proven track record of sacrificing the interests of its supporters to maintain business profits and capitalist stability.

That’s why, whoever wins on 2 July, we need to rely on our own strength. The only way that we will win genuine reforms is by a sustained fight in the workplaces, on the streets and on the campuses. And to lead those struggles, we need to build a fighting socialist left that breaks with the pro-capitalist consensus endorsed by Labor, the Liberals and the Greens.