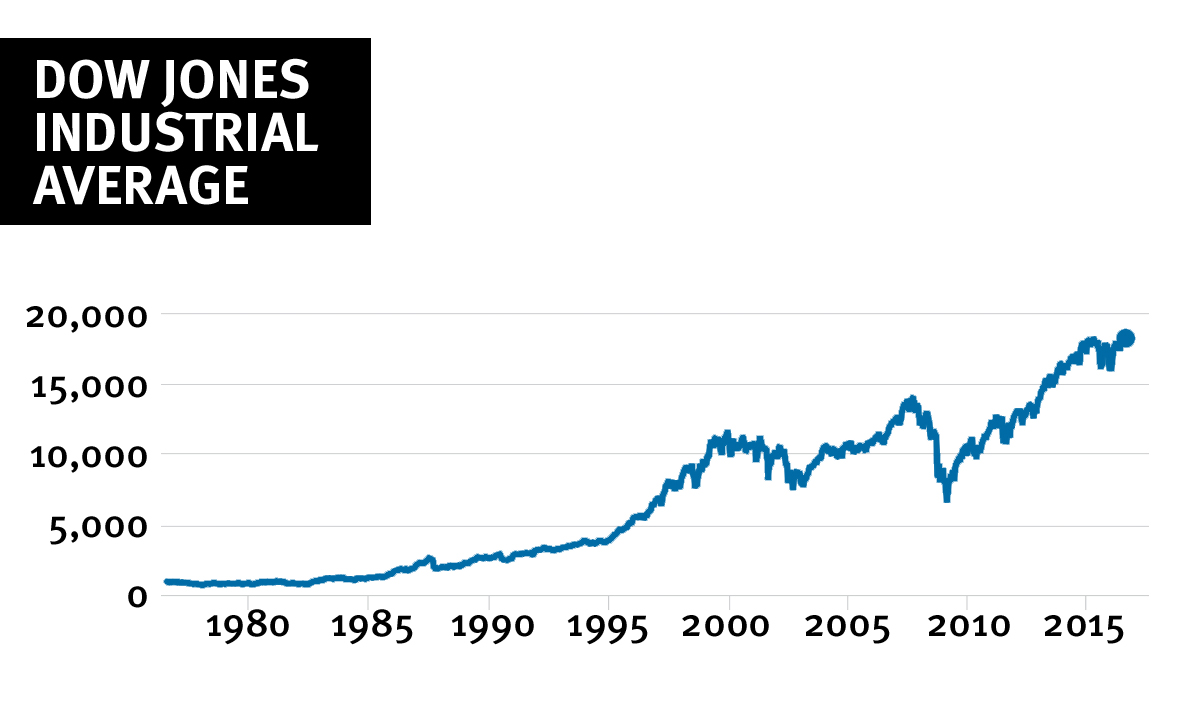

Gyrations on international stock markets, over fears that the US Federal Reserve Bank might soon raise interest rates, remind us that all is not well in the global economy.

The recent turbulence in equity prices comes after several months of share market recovery, following prices around the world dropping sharply earlier in the year. Just prior to the big drop on Wall Street on 9 September, the Dow Jones industrial average was up by 18 percent, the British FTSE 100 by 25 percent, the German DAX index by 22 percent, the Japanese Nikkei 225 by 13 percent, and even the nervy Shanghai index, which soared only to collapse in 2015, was up by 14 percent.

Despite the rise in share prices since February, there is anxiety among investors. While money is being pumped into stock markets, it is also pouring into bond markets. Investors are looking for a safe haven, even if the return on bonds is negligible or, in an increasing number of cases, negative. Another indication of wariness towards equities is the predominance of defensive (dividend-focused) stocks, such as telecoms, utilities and consumer staples.

The mood is underpinned by recognition that the real economy is not healthy. One reflection of this is the high price-to-earnings ratios for leading stocks: companies are not earning the kind of profits needed to justify their elevated share prices.

SOURCE: Google Finance

Why, then, have stock markets in several countries been charging ahead? On one hand, central banks are printing money in a desperate attempt to boost spending and lift inflation, so the funds for stock market speculation are freely available. On the other, equities are the best thing going; everything else is looking bad. Money in at-call or savings accounts is earning pitiful returns. Corporate bonds are less appealing due to high levels of company debt, rising defaults and disappointing profits. There are fewer opportunities for profitable investment in productive industry because of low rates of economic growth and stagnant world trade.

Stock markets have been rising because of pure momentum: rising prices are attracting buyers, pushing up share prices, attracting more buyers. Momentum can work as long as investors believe that share prices will keep rising. Once realisation sinks in that prices cannot be justified by future earnings growth – possibly when the Federal Reserve lifts interest rates again before the end of the year – all bets are off. In these circumstances, any dip in the markets, such as occurred in the last northern winter, can lead to a rout as investors sell in unison.

The real economy, where surplus value is created, is what matters. Here the situation is not good.

Sputtering on three cylinders

Of the major Western economies, the US has led the pack since the global financial crisis. Annual GDP growth has averaged 2 percent since 2010, and the unemployment rate has halved to 5 percent. Nonetheless, the recovery has been the slowest on record and is already wearing thin: investment and corporate profits have fallen for three successive quarters, and growth is now down to 1.1 percent. Manufacturing has suffered from the rise in the US dollar.

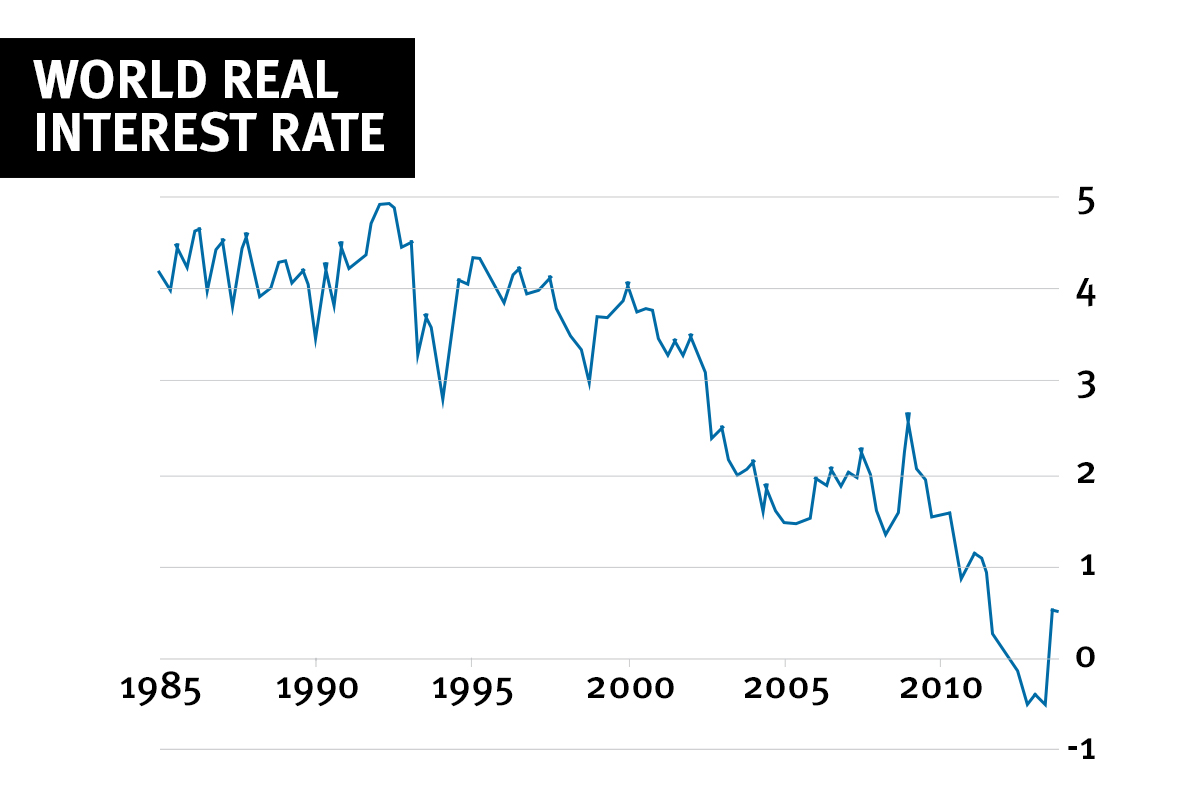

The listlessness is part of a longer term malaise: since 2000, US annual growth has averaged just 1.75 percent, half the level of the previous 50 years. Household incomes are no higher than they were at the turn of the century. Four predicted interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve Bank in 2016 were abandoned as it became clear that the economy was in no state to deal with a return to monetary policy “normality” – that is, the return of interest rates to historic levels.

Britain, another supposed global financial crisis recovery story, is not faring any better. Growth is not expected to exceed 1.5 percent in 2016, and prospects for 2017 are very uncertain: investors are still sitting on the sidelines to see what steps the government will take in response to the Brexit vote. Median household income rose in 2014-15 but, having previously fallen for several successive years, is no higher now than at the onset of the global financial crisis.

SOURCE: McKinsey&Company

In the Eurozone, growth of only 1.6 percent is predicted for 2016, and unemployment, seven years after the worst of the global financial crisis, is still more than 10 percent. The debt crises in Ireland and Spain have attenuated, but several Italian banks are under serious stress. Greece is still in depression.

In Asia, Japan is faring the worst of the three big economic powers. Fiscal and monetary expansions have failed to lift growth beyond 0.7 percent in the past two years. The yen is seen as a safe haven currency and has been climbing steadily on the back of foreign investment; its rise, however, is jeopardising exports, which are already under pressure from a slowing Chinese economy. India, now the seventh largest economy in the world, is growing at 7 percent per year – faster than any other major economy. But a drop in growth in the second quarter demonstrates that not all is smooth sailing. Prime minister Narendra Modi’s neoliberal economic program is premised on a big influx of foreign investment, and yet FDI inflows into India have been sliding over the course of 2016.

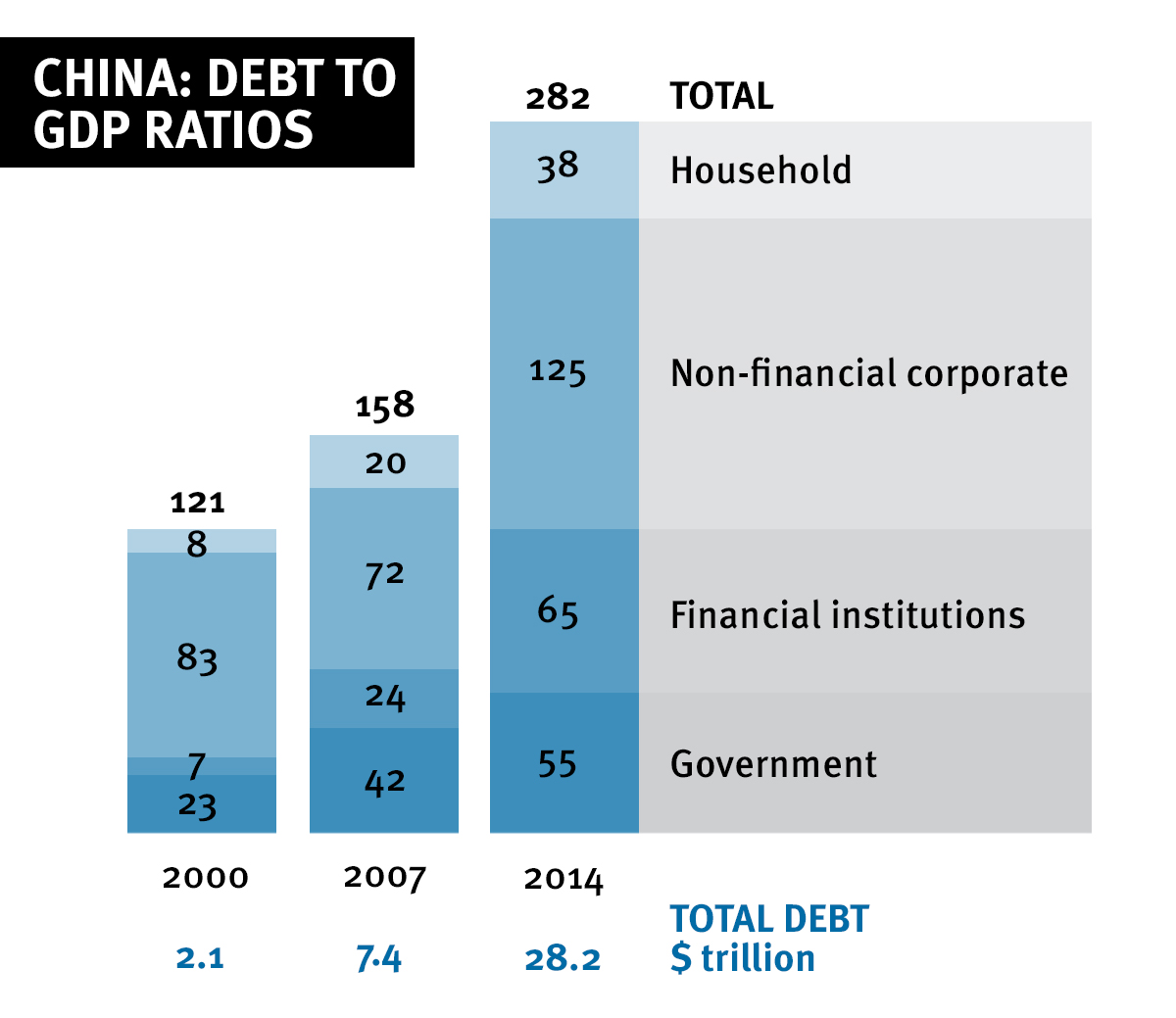

China’s growth rate has fallen from 12 percent in 2010 to 6.7 percent this year, the lowest in a quarter of a century. A revived government stimulus program over the northern winter helped the property market recover and, with it, steel production. But the fiscal splurge added to the massive accumulation of debt, which now stands at 260 percent of GDP. Corporate debt alone is valued at 160 percent of GDP, double the already high level of the US. Much of the country’s financial system relies upon on a highly opaque shadow banking sector that mimics in all its worst aspects the second and third tier US banks that flourished during the housing boom of 2002-07.

Further, a considerable amount of the borrowed money in China has been invested in industries that are becoming less effective at generating income. Indeed, the additional borrowing may result in an accumulation of losses, jeopardising the ability of corporate China to repay its loans and adding to the pressures on the country’s banking system.

China is also suffering capital flight as its billionaires try to escape the effects of the falling yuan and a vigorous anti-corruption purge by president Xi’s government. In 2015, approximately $1 trillion was taken out of the country, reducing its enormous foreign exchange reserves.

SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute

For the big primary commodity exporters, the last five years have been rough. The commodity bust has hit not just mature developed economies such as Canada and Australia but also, and with greater force, the big mineral and energy exporters: Russia, Brazil, Venezuela, South Africa, Nigeria, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states. Brazil and Venezuela are both suffering economic slumps, the South African economy is contracting, and the government revenues of oil-producing African and Middle Eastern countries have been smashed.

The so-called emerging market economies, once seen as a bulwark for the world economy against stagnation in the West, are now part of the broader malaise. The only bright spot for these countries has been the recovery of commodity prices since the start of the year, powered by rising Chinese steel production.

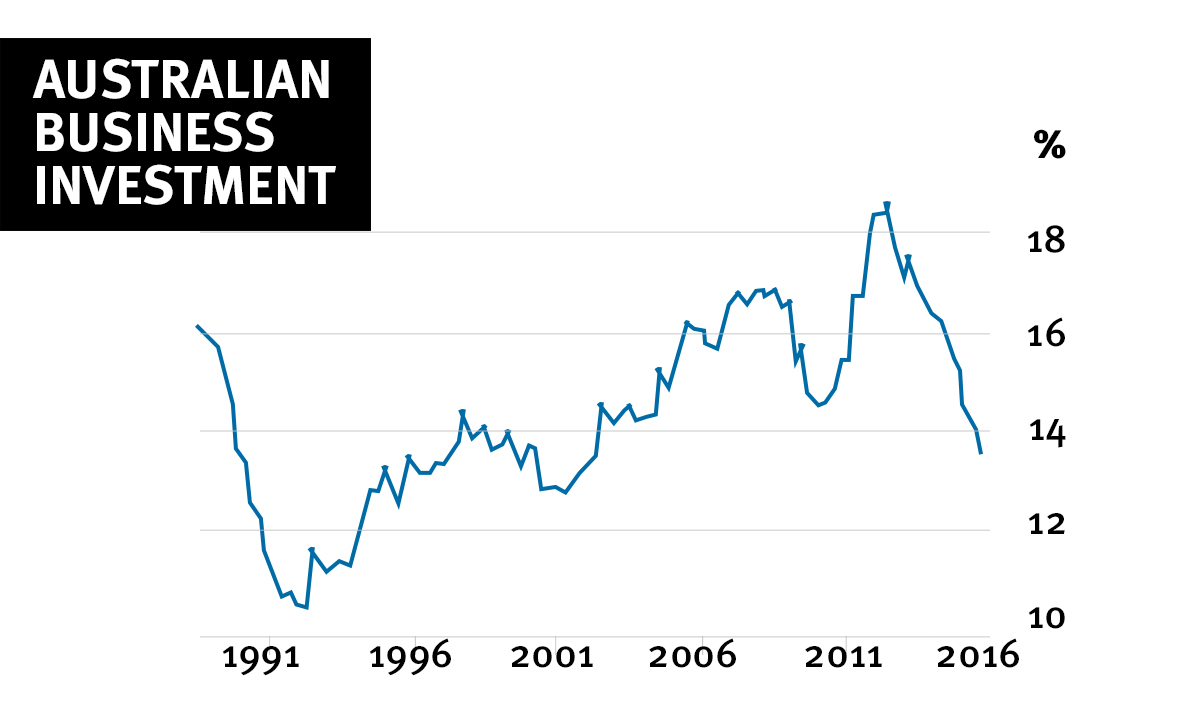

In Australia, the transition from the mining investment boom has gone more smoothly than might have been expected five years ago, when commodity prices started to fall. Economic growth at 3.3 percent in 2015-16 is more than double the G7 average. After some years of stagnation and decline, real net national disposable income is now recovering as commodity prices rise. Consumer spending has held up, and coal and iron ore export volumes have increased. Outside mining and manufacturing, corporate profits have grown.

The real estate boom centred on Sydney and Melbourne has been the focus of growth in Australia, pulling up residential construction and services related to real estate, including the banks. Growth has been uneven, with Victoria and New South Wales leading, although the former is now beginning to slow. Western Australia and Queensland have lagged. Real unit labour costs have fallen over the past 12 months, as wages rise at the slowest rate on record. Unemployment has remained relatively low, and the labour force participation rate among 16-64 year olds has been climbing.

SOURCE: Reserve Bank of Australia

But there are evident problems for the bosses in Australia: forecasts vary, but apartment construction appears to be heading towards a glut – construction of units has grown by 28 percent over the past year – and the flood of new product coming onto the market may drag down prices, impairing the balance sheets of banks heavily engaged in property lending.

Investment may have grown outside mining and manufacturing but not by nearly enough to compensate for the collapse of investment within those two sectors – overall capital expenditure is down by a third from its peak in mid-2012 and is forecast to fall further. Economic growth may be better than in many other countries, but has been trending downwards since 2003. The participation rate may be growing, but almost all of the jobs growth since 2015 has been in part time work, resulting in only very meagre growth in hours worked. Finally, household debt continues to climb and now stands at 180 percent of GDP, raising risks for the banking and financial sector.

In short, although the situation varies from country to country, the world economy as a whole is sputtering along on three cylinders and has failed to recover fully from the crash of 2008-09.

SOURCE: Mervyn King “Measuring the World Real Interest Rate”

With low interest rates failing to revive industry, the economic and financial authorities are engaging in the kind of stimulus packages used to revive economies at the height of the global financial crisis. For some years, the US government has been pressuring the EU to wind back the austerity regime favoured by the German government. The introduction of the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing program in 2013, involving the purchase of bonds from European banks, combined with cuts to its deposit rate to minus 0.4 percent, represent significant steps away from German economic rectitude, much to the annoyance of German banking chiefs.

Since then, some governments have relaxed their fiscal policies. The IMF is urging member governments to borrow in order to invest in infrastructure. Central banks are also seriously considering “helicopter money”, by which they will buy government bonds, allowing governments to inject the money directly into the pockets of households and businesses.

Fiscal relaxation and unorthodox monetary policies, however, are a direct challenge to the economic orthodoxy of the past three decades, and there is no guarantee that they will be fully implemented. Opponents can point to the fact that government indebtedness is already far higher than at the time of the first round of stimulus packages in 2008-09, and that these failed to provide the basis for any sustained recovery. Why should it be any different this time around?

From neoliberal recovery to depression

Marxist economist Michael Roberts, in his new book The long depression, argues that the weakness of the post-GFC recovery and the failure of investment to respond to low interest rates are indications that the advanced economies are mired in a depression. I think that’s right.

Just to be clear what is meant by this: a depression is not restricted to periods of deep slumps in output, investment and employment, and skyrocketing unemployment that we associate with the Great Depression of 1929-32. Roberts uses the term to describe a situation in which economies are growing well below their previous rate and below their long term average; when investment and employment are well below the previous peaks and below long term averages; and, above all, when the profitability of the capitalist system remains, by and large, lower than levels that existed prior to the start of the depression.

Capitalism has experienced three such depressions: the first in the late 19th century (from 1873 to 1897); the second in the 1930s, ended only by World War Two; and the third, the current conjuncture. Each started with significant financial crashes (in 1873, 1929 and 2008 respectively), but at the heart of every depression is profit. The key to understanding the current depression is the fact that the rate of profit is too low to stimulate the surge in investment necessary to underpin a new round of economic expansion.

That profits are too low to stimulate the real economy might seem counter-intuitive. It’s true that the mass of corporate profits has rebounded strongly since the global financial crisis and the share of profits in global GDP has recently been close to postwar highs. However, the global non-financial rate of profit – and it is the rate of profit that counts – has been declining on a secular basis since the late 1990s. Understanding the significance of this requires a brief review of recent economic history.

Following the economic crises of the 1970s and early 1980s, the rate of profit in the US and other advanced economies began to recover. Several factors were responsible. The most important was the increasing rate of exploitation of the working class, which involved mass sackings, union busting, wage cuts, speed-ups and cuts to the social wage. From the 1990s, these methods were supplemented by the entry of China as a major manufacturing centre. China’s industrial take-off allowed Western companies to reduce the cost of labour power by offshoring or outsourcing to China (or threatening to do so) and reduce the socially necessary labour time required to reproduce labour power in the West by the mass import of cheap consumer goods.

The second factor responsible for the recovery in the rate of profit was the destruction of constant capital through the shutting down of large industrial centres, such as the steel industry of the US mid-west, along with bankruptcies and waves of mergers. The third factor was the cheapening of constant capital associated with the widespread application of information technology to productive and service industries. These factors together ensured that profitability increased. However, the rate of profit never regained the levels enjoyed by the capitalists during the long postwar boom in the 1950s and 1960s. As a consequence, growth rates and investment shares were lower.

In the US, the profitability revival lasted until 1997, at which point it again began to decline; US capitalists searched out other outlets for their money – betting on the stock exchange or buying various other financial instruments. The result was the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, in which the stock market valuation of supposedly “hot” IT companies exceeded their revenues by many multiples. The bubble burst in 2000 and was followed, after a short, sharp recession in 2000-01, by a massive housing bubble.

The housing bubble was accompanied by the expansion of household borrowing, as workers used the rising value of their homes to borrow more from the banks, sometimes even to buy an investment property, kicking the property market along. Off the back of the housing bubble grew the whole industry of derivatives and other exotic financial instruments.

In 2007, the housing bubble burst in the US. Home owners able to walk away did so, forcing the banks to bear most of the loss. Those who couldn’t either had to sell up and take a big loss or endured years of negative equity. Working and middle class living standards fell. The result was a drop in home lending and household spending and the rapid deterioration of bank balance sheets.

Despite the ups and downs of the housing market, the underlying problem was that the rate of profit in productive industry was too low to attract investment. Therefore, the production of real value, as opposed to the paper value of inflated property markets, was held back. The growing preponderance of fictitious capital – speculative increases in the value of real estate and highly geared financial derivatives – yielded higher profits for a period, but also meant that any bust in the housing markets or the stock market would expose the shaky foundations of the recovery.

So, while the global financial crisis initially took the form of the sub-prime crisis – the financial sector is often where crises start – low profitability in the productive sector was the underlying cause. Starting in early 2006, the mass of profits began to fall, alongside a fall in the rate of profit, causing a rapid decline in investment that in turn fed into the economic bust of 2008-09.

The global financial crisis began to abate with massive government rescue programs for the banks and, in some countries, stimulus spending that reflated household and business spending. Profits started to improve in 2009, prompting a recovery in investment, which then brought about a turnaround in GDP in 2010. In the following years, the mass of profits and the profit share of GDP rose strongly. However, since 2015, both have begun to turn down, and the rate of profit, not just in the US but in all the major economies, is still below its pre-crisis level and well below the neoliberal peak of 1997.

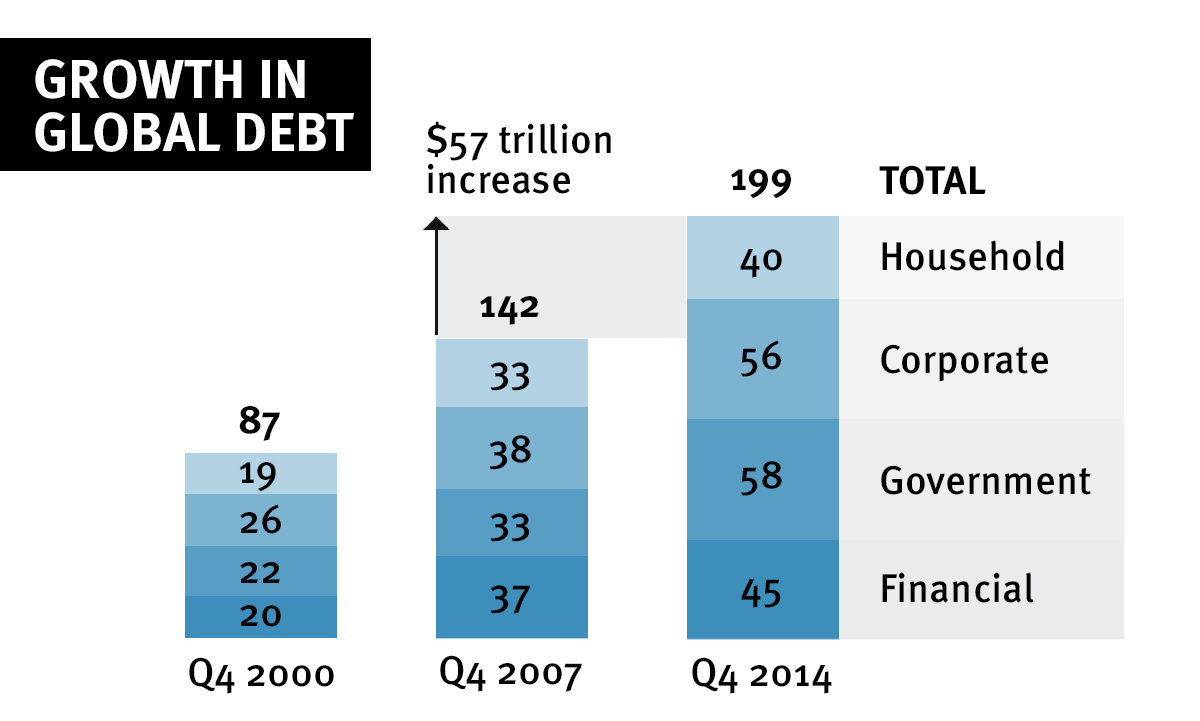

While profitability still lags, corporate, government and household debt has grown enormously since the 1990s. Corporate debt in the advanced economies now stands at 113 percent of GDP, government debt at 104 percent and household debt at 90 percent.

The lower rate of profit and the high levels of corporate debt, combined with recent declines in the mass of profits and the share of profits in GDP, are reducing the dynamism of the system. With investment low, labour productivity growth, the basis for long term economic revival, is sluggish. These factors explain the depressed conditions in the advanced capitalist economies and the nervous mood in the stock markets.

A way out?

Capitalist crises have in the past sown the seeds of recovery by creating the conditions for big cuts to the value of labour power (by forcing down wages), intensifying the labour process and devaluing constant capital (through bankruptcies and fire sales or the physical destruction of machinery and equipment that is left to rust).

In the current depression, the cheapening of labour power and destruction of fixed capital haven’t occurred to the degree required to give the system a new shot of energy. One problem is that individual capitals are now so big, so intertwined with each other and so enmeshed in the state that governments often jump in to prop them up to prevent a broader economic collapse that would take down otherwise viable companies. While such interventions may prevent a collapse, they nonetheless delay the purge of capital that is required to clean out the system.

It is conceivable that states will allow some big companies to fail – during the global financial crisis, for example, the US government oversaw rationalisation at General Motors and allowed several big banks and insurance companies to go to the wall. Corporate defaults in the US are now at the highest rate since the global financial crisis, with oil and gas companies top of the list. However, there is no sign of broad capital wipe-out.

In the US and the UK, some bank and household debt has been written down, because banks have shrunk and many homeowners have defaulted on their mortgages. In the EU and Japan, by contrast, bank and household debts have increased since the global financial crisis. In Italy large swathes of the banking system are unstable, and in Germany the books of Deutsche Bank, the country’s financial behemoth, are weighed down with risky loans. But even in the US and UK, debt reduction has not been sufficient. In the non-financial corporate sector in the US, deleveraging has been even less apparent. Partly because of large debts, companies are not engaging in big new investments or new hiring.

Further, the decrease in private debt in the US and UK has been outweighed by the growth of public debt. The global financial crisis resulted in a sharp drop in tax receipts and increased spending on welfare and social security as unemployment soared. Bank bailouts also contributed to the build-up of public debt. The result is that overall debt to GDP ratios across the OECD are at record levels and, as noted above, higher still in China, which is now a much more significant element of the world economy than at the onset of the global financial crisis.

As for the cheapening of labour power, employer initiatives, austerity budgets and all-out attacks on trade unions and the minimum wage have been effective in forcing down the cost of labour both in the weaker economies like Ireland and Greece, but also in Germany and Britain. McKinsey consultants recently reported that two-thirds of households in 25 high income countries had stagnant or falling incomes between 2005 and 2014.

Nonetheless, the reductions that have been carried through are not enough to restore profit margins to the degree necessary to get the capitalists to invest significantly. Without the necessary purge of capital and cheapening of labour power, there is a limit on the economic recovery. That’s why it has been the weakest on record.

This is not to say that an economic slump is imminent. With various government stimulus programs now under away, GDP might be propped up for longer. Earnings reports to Wall Street in the northern summer were better than forecast. Chinese growth is running higher than anticipated. Brexit has not led to economic collapse in the UK. US interest rates will be lifted only cautiously. But the world economy is no closer to rude health than it was in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. In the event of another slump, the tools used to mitigate the 2008-09 crisis will be less potent next time because of the greater levels of government debt and because monetary loosening has gone as far as it can.

The only way that the capitalists have out of this is to increase attacks on the working class. Hence the IMF’s recent call for further “structural reform”, that is, more redistribution of wealth to the capitalists. This will remain the dominant feature of class relations around the world. The more far-sighted figures in the ruling class can see the dangers of economic inequality and the political polarisation to which it gives rise, but the crisis pushes them to maintain the offensive. More and more we can expect to see curtailment of democratic expression as a result.

Imperialist rivalry

The depressions in the late 19th century and the 1930s increased tensions between the great powers, both established and emerging. The situation is no different this time as each government tries to force upon another the cost of economic adjustment. Protectionist measures increasingly are applied. So far, they are modest in scale, mostly comprising anti-dumping measures initiated by steel companies trying to protect their home markets. But greater application would be a real threat to the more internationally integrated capitalists. And their numbers are growing – one-half of the revenues of the US’s biggest 500 companies now comes from overseas, a radical departure from the situation in the postwar decades, when US capitalism was focused mainly on its home base.

Even if a turn to full-blown protectionism on the lines of the 1930s is unlikely, the ongoing crisis has stymied moves towards the removal of barriers to international trade and investment embodied in yet-to-be-ratified multilateral trade agreements such as the 12-member Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the 28-member EU-US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

In the US, both presidential candidates now say they are against the TPP. And there is serious opposition to the TTIP among senior government figures in the EU. The French trade minister complained in August: “There is no political support in France for these negotiations. The Americans give us nothing, or just crumbs”. Business leaders, the financial media and the IMF are growing increasingly anxious that political support for globalisation is crumbling.

Other indications of imperialist gridlock include the failure of the Doha round of the WTO and the tensions on display at the September G20 summit in Hangzhou in China, at which the hosts were targeted by their Western rivals as disrupters of international trade. Hangzhou demonstrates that the unanimity of purpose displayed at the first G20 summits in Washington and London at the height of the global financial crisis is now long gone and that the G20 as an instrument of international coordination is dramatically weakened.

The impact of Brexit on the integrity of the EU is also unknown. From the perspective of European advocates of “ever closer union”, the situation is going from bad to worse, with the potential for wholesale disruption to the architecture of European integration built up over the past six decades. Such an outcome would be a blow not only to ruling classes across the EU but also to the US establishment, which has overseen and encouraged the EU project since its inception in the 1950s.

Inter-state tensions also take a military form. Over the past couple of years, tensions have escalated between the US and its allies, including Australia, and China over rival claims in the South China Sea. Even if the US’s planned “pivot to Asia” has not proceeded as quickly as first envisaged because of intractable problems in the Middle East, the US and China are both clear that the Asia-Pacific is going to be a region of much greater military contestation in coming years and are preparing accordingly.