“Today is an emotional day for all of us at Ford”, remarked Ford Australia president and CEO Graeme Wickman as the final Ford Falcon rolled off the assembly line at the Broadmeadows plant on 7 October. “We are saying goodbye to some of our proud and committed manufacturing employees and marking an end to 91 years of manufacturing in Australia.”

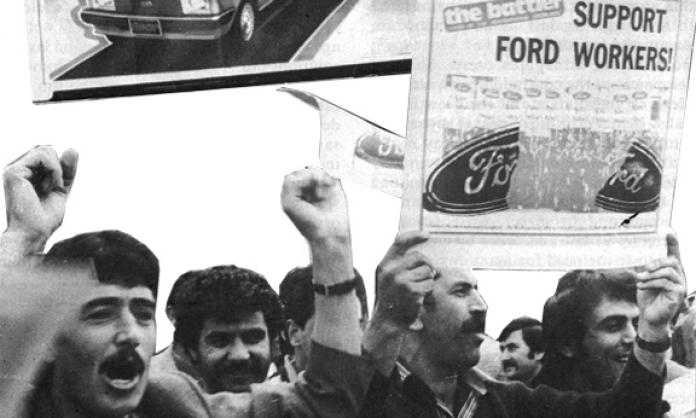

But in all the company’s tributes to these “proud” workers, no mention was made of the workplace militancy that once characterised the plant. At its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, Ford Broadmeadows was home to one of the best organised networks of union activists in manufacturing industry.

‘Incipient revolt’

The Broadmeadows complex was opened by Ford in 1959. Its aim was to expand production, which had been previously restricted to Geelong.

Compared to the Geelong facilities – where the pace of production was moderate and management-union relations docile – Broadmeadows would become the stage for major collisions between ruthless factory discipline and worker discontent.

A sprawling assembly line that extended for miles meant that workers’ movements were calculated and monitored down to a fraction of a second.

The largely migrant workforce was routinely harassed by management and foremen and regularly referred to as “wogs” and “dagos”. Workers were denied tea and toilet breaks, often forced to relieve themselves on the assembly line. Bonuses were awarded to those who arrived on time and kept up with production targets; enormous penalties were imposed on those who didn’t.

Yet these extensive assembly lines – dependent upon strict coordination – meant that small groups of workers could easily disrupt the entire production process. Amalgamated Engineering Union tradesmen, led by Communist Party militant Sol Marks, and Vehicle Building Employees’ Federation shop steward Ron Gent, quickly saw the potential for shop floor organising.

Several stoppages soon followed: about the supply of tools, demarcations between the trades, payment of “dirt money” (compensation for working in poor conditions) and the racist behaviour of managers and foremen. Work practices that had been grudgingly accepted by workers now became open for dispute.

These small stoppages culminated in a series of plant-wide strikes in the 1960s and 1970s. The idea that strikes and other militant action could improve working conditions became popular across the plant, and in each dispute workers learned lessons that they would apply to later struggles.

Joint action across different sections of the floor was understood to be decisive to success. Racism was seen as another bosses’ tool that pitted sections of the workforce against each other.

Organisationally, the formation of strike committees in each dispute led to the creation of an expansive activist network throughout the plant and across the car manufacturing industry. In many instances, these networks openly defied union leaders when it was thought they were not acting in the interests of workers.

But despite important victories, work conditions at Broadmeadows were still far from humane. After a sharp rise in demand for cars in 1973, Ford increased the pace of the assembly line and introduced new shifts. The extreme pressure of work – combined with widespread working class and student rebellion across Australia – led to what Sol Marks described as an atmosphere of “incipient revolt”.

The “incipient revolt” broke out in a riot during a nine-week 1973 strike after union leaders attempted to rig a vote declaring the strike over. A wall was pulled down, windows smashed, a fire hose turned on the company offices and police pelted with tomatoes and other fruit. Furious that workers were seen smiling as they stormed the factory, the Melbourne Herald editorial declared: “That Ford affair was not funny”.

Workers won a pay increase, the transformation of the bonus scheme into a straight over-award payment and significant improvements in relief and tea breaks. Racist behaviour amongst management and foremen became a relic of the past.“We showed the company that the people were not slaves”, an assembly-line worker remarked in an interview afterwards. “They started being afraid of the workers and the union.”

‘Consensus’ and ‘responsibility’

But a series of defeats suffered by workers in the early 1980s – combined with a protracted economic crisis – meant that these activist networks did not last.

The economic crisis hit manufacturing industry the hardest. Mass sackings were taking place across the car industry. Debates opened up about the appropriate response from unions.

The leadership of the manufacturing and metal unions blamed the crisis on a lack of tariff protection, and pinned their hopes on an ALP government protecting the industry.

Dissenting voices, led by Ford shop stewards, presented an alternative strategy. They formed an opposition ticket in the 1981 and 1982 Victorian branch elections and blamed the crisis on the drive to accrue profits by the companies. Their platform declared: “The bosses must pay for the crisis, not us!”

The opposition demanded an end to sackings in the industry, the introduction of a 35-hour week, a $50 catch-up wages claim, sit-ins to save jobs and nationalisation of companies under workers’ control if it proved necessary. They also demanded a full democratisation of the union, including full-time officials’ and stewards’ positions being made subject to instant recall.

The tickets, however, were defeated. While there was disillusionment with the leaders, they were able to cling to power because of widespread demoralisation and the job security fears of a majority of workers at other car plants.

The shop stewards – with their alternative strategy defeated – instead followed the orientation provided by the union leadership. In 1983, they accepted the notorious Prices and Incomes Accord between the Hawke government and the ACTU. The stewards pledged “to bring about economic recovery by consensus and through equal sharing across all groups of the community of economic responsibility”.

“Consensus” meant policing a “no strike” policy; the sharing of “economic responsibility” meant crafting a series of rescue plans for the industry. The role of unions was now to ensure the survival of the sector by making it more competitive internationally. This meant accepting job cuts and playing a role in restructuring industry.

The strategy proved disastrous. It allowed Ford to carry out large-scale redundancies without any opposition. The stewards promoted labour flexibility and increased productivity through a series of “participative management” schemes.

Rather than the industry being saved, it has now been restructured out of existence. The closure of the remaining Ford assembly plants in Broadmeadows and Geelong is testament to that legacy.

Part of that legacy, however, is also the alternative first argued for by the shop stewards. Rather than accommodation to the bosses’ demands, they preached confrontation. As one worker at Broadmeadows remarked in the 1970s: “If anyone was sacked here the place would stop at once, and they know it”. They put the bosses on notice that workers would fight – that to attack jobs would cost them.

And instead of relying on the empty promises of politicians – and those union leaders willing to compromise with them – the shop stewards understood that it was the initiative and efforts of workers themselves that pointed in a direction that could win.

In 1981, in the middle of the battle to reform the union leadership, Ford shop steward Frank Argondizzo wrote: “Time is on the workers’ side; the workers have learned to be patient”. Time eventually ran out for the Ford workers, but the lessons of their struggles remain as relevant as ever.