There is general agreement that the inexorable rise in inequality, Scott Morrison’s denials notwithstanding, has something to do with government policies over the past quarter of a century. Everyone from the IMF’s Christine Lagarde to ALP leader Bill Shorten agrees on that.

But it’s more than just wrong government policies. The fact that inequality is now at its highest since World War Two is down to the ruling class as a whole, bosses and governments, waging a war against the working class and, crucially, the failure of the established leaders of the working class movement to fight back.

The source of inequality

Inequality is not an aberration in the capitalist system. It is a necessary condition for it. Capitalism requires that a minority own or control the means of production while the majority are denied any say over how these means of production – the factories, the offices, the wharves, the railways, the mines – are used and for whose benefit. How and why else would the working class turn up to work for a boss every day if the situation were any different?

But inequality doesn’t exist today because somehow, through thieving, sharp practice, inheritance or good luck, the bosses got their hands on the good things of life some centuries ago and just hung on to them. Inequality is constantly reproduced and exacerbated by the workings of the capitalist system, day in, day out. Capitalism is an inequality-generating machine.

At the heart of inequality lies the exploitation of labour. The working class never gets the full fruits of its labour. People work eight or 10 hours a day for the boss but get paid the equivalent of what they create in three or four hours – the rest goes into the hands of the capitalist class. If an individual worker objects, the boss can tell them: “You don’t like it, go and work somewhere else”. And, lo and behold, the same process operates there too. There’s no escape from exploitation so long as we have capitalism.

But there is no iron law that says whether the bosses will pay us the equivalent of three or four or five hours of our labour. It’s true that they need to pay us enough for us to reproduce ourselves – physically, psychologically, emotionally – otherwise they would quickly exhaust the pool of available labour. But beyond that basic minimum, there’s scope for variation. And that variation is determined by the class struggle.

Strikes and inequality

The fall and subsequent rise in the level of inequality in Australia over the past six decades is squarely down to the ebb and flow of class struggle over those years.

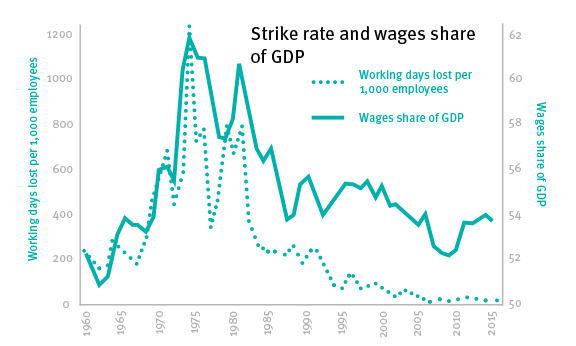

During the period from the 1950s to the early 1980s, inequality in Australia fell. One indication of this was the rising share of employee earnings as a proportion of national income; we call this the wages share.

While lots of factors contributed to the rising wages share – one was the fact that pretty much everyone who wanted a job could get one – it was working class struggle that really drove the process.

This was obvious from the mid-1960s, when workers went on the offensive for higher wages and better conditions. Between 1964 and 1974, the strike rate soared and, as it did, so too did the wages share of national income.

There was a brief relapse in the middle to late 1970s as the effects of the Whitlam sacking and mass redundancies associated with a sharp recession dented workers’ confidence. As the strike rate dropped, the wages share of income also fell.

But then workers went back on the offensive in 1979, and in 1981 the strike rate exploded once again. Workers smashed through attempts by the Arbitration Commission (the predecessor of the Fair Work Commission) and Fraser government to hold down wages.

The strike offensive from 1964 to 1981 had many other beneficial effects for the working class. For a start, it helped to build the union movement. Union membership grew from 1.8 million to 3 million between 1961 and 1981 as whole new layers of white collar workers, predominantly women, were drawn into the movement. For the first time, many of the workers who had traditionally regarded themselves as “a cut above” blue collar militancy, such as teachers, nurses and public servants, began to stop work to hit the streets.

Working class combativity also shifted the broader political climate to the left. In the 1960s, workers began to move into action around the Vietnam War, South African apartheid, Aboriginal rights, equal pay for women and a host of other issues. More than two dozen Victorian unions split from the right wing Trades Hall in 1967 and banded together for more effective action. And in 1972, the 23-year reign of the conservative parties was brought to an end. The incoming Whitlam government was pushed to adopt a more reforming agenda than Whitlam himself had wanted. It was forced to tack left under the impact of struggle by workers and by university students.

From boom to bust

So what changed? In 1983, the union leaders turned their backs on the idea of class struggle. They struck a deal with the Hawke Labor government, called the Prices and Incomes Accord, which started the rot. Under the Accord, the union leaders agreed to abandon striking in return for having wages indexed by the Arbitration Commission and promises by the Labor government of a few social reforms.

The effect was disastrous. With strikes in a tailspin, real wages fell and the wages share began its long decline. The Accord ended in 1996, when the Keating government was defeated by the Coalition under John Howard. The new government went much more openly onto the offensive against the union movement. But the unions were not just bystanders. They had the capacity to push back, but didn’t.

There were two major episodes when our side could really have turned the tide – the 1998 waterfront dispute at Patrick Stevedores and the 2005-07 union struggle against the Howard government’s union-busting WorkChoices industrial laws. But in both cases, the unions pulled their punches, and the campaigns ended up falling far short of what could have been won.

Since that time, the resources of the union movement – money and staffing – have been poured into electioneering. Not just at election times but for years beforehand: the ACTU is already gearing up for the next federal election campaign two years before the elections are due.

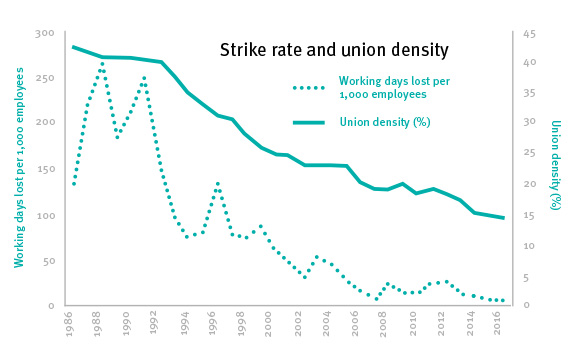

With few exceptions, strikes have been pushed aside: in 1974, at the height of the strike wave, the average worker was on strike for 10 hours a year; in 2016 the figure was just four minutes.

Abandoning strikes has led to a retreat across the board. Union coverage has collapsed. Union membership is just one in seven workers, down from one in two in the early 1980s. The crisis is the worst in the union movement’s history.

Workers in retreat, bosses on the offensive

The collapse in strikes and union coverage is what lies behind today’s rampant inequality. Fewer and fewer workers have their wages and conditions protected by union agreements. Real wages are falling, particularly in the private sector and for the young, who are disproportionately in low-paid and vulnerable jobs.

In non-union enterprises, wage theft is rampant, workers are robbed of their superannuation, and basic entitlements such as penalty rates are often withheld.

With unions weak and for the most part industrially ineffectual, the Fair Work Commission has had a free hand to launch savage attacks, including cuts to penalty rates and miserly increases to the minimum wage, pushing it down to historic lows when compared to the median wage.

The employers have had a free hand to push workers around. So-called “restrictive work practices”, which limited management’s assumed prerogatives to direct workers on the job – deciding what breaks are taken, what safety provisions are observed, how workers can be sacked or disciplined, what employment contracts workers are under (direct employment, labour hire, independent contractor) – have been whittled away in many industries, degrading skilled labour and pushing up the intensity of work.

And, finally, the lack of combativity in the working class has allowed successive governments to strip away social security entitlements by reducing their real value, restricting eligibility to increasingly narrow sections of the population and introducing more and more onerous “mutual obligation” requirements.

The decline in working class struggle has also had an important ideological effect. Trade unions are the basic combat organisations of the working class, and strikes are the equivalent of warfare. Their absence from so many industries dilutes a basic sense of working class identity and encourages individualism, with all of the toxic effects that go with that – crawling to the boss, doing down your workmates and so forth. Fracturing solidarity at the workplace also opens the door in society more widely – in the parliamentary, media and educational spheres – to the far right.

There’s been a lot of talk in the union movement in recent months about the need to “change the rules”, to fight for an overhaul of the Fair Work system of industrial laws designed by Bill Shorten when he was a minister in the Gillard government. And ACTU secretary Sally McManus has said that unions have the right to break unjust laws.

But, so far, this has all been at the level of speeches and rhetoric. This rhetoric has to be backed up by action. That means a return to the struggles that put a serious dent in inequality last time around in the 1960s. It means a fighting union movement with a strategy to push back against right wing attacks, no matter who is in government. And it means a struggle within the union movement against the dead weight of the strategies that have dominated for more than three decades.