Opposition is growing to the Victorian state government’s audacious plan to demolish up to 11 public housing estates and sell the land to developers. More than 150 public tenants and supporters gathered in a park at the base of the Flemington high rise estates on 15 October to celebrate and defend public housing. The rally was organised by the Public Housing Defence Network, a new group formed to oppose the sell-off of public housing.

Neville, a 30-year resident of Gronn Place, a West Brunswick estate targeted in the government’s plans, opened the rally with an inspiring call to resist. He vowed to chain himself to his house if the government tries forcibly to move people off the estates. The Gronn Place estate is a closely knit community that is home to around 90 children, many of whom have never lived anywhere else. Along with thousands of other public tenants, they are on a time line to eviction, if the government gets its way.

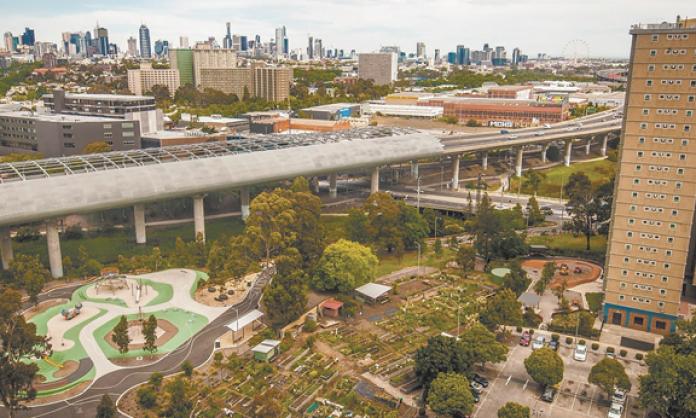

The misnamed Public Housing Renewal Program is a state Labor initiative designed to open up pockets of valuable inner city land for high density private development. More than 1,000 low rise public housing units will be knocked down and the land cleared to make way for Docklands-style apartment towers. The government has budgeted $185 million for the plans, which will net Victoria no additional public housing but will result in 5,000 new private apartments being crammed onto the estates. Any “social housing” built on the estates will be given to non-government housing associations.

Public tenants are being promised they will be able to return to their estates after the developers are finished. They are not being told that none of the new homes will be public housing. Many tenants have also been shocked to discover by reading the fine print that only a minuscule fraction of any new “social housing” will be big enough for families. The new buildings will be almost exclusively filled with one- and two-bedroom units. Most families moved off the estates will be permanently displaced.

At the rally, Egal, a resident of the Abbotsford Street estate in North Melbourne, gave a powerful speech about what the estate means to his family. “I’ve got an anaphylactic child; he goes to the school around the corner and the children’s hospital is also around the corner. I’m not interested in a mansion in Toorak, I’m interested in my little area where I feel comfortable.”

Egal and Neville were just a few of the public tenants who spoke proudly about the bonds formed between tenants on the estates. With the government’s rhetoric about the need to build “new vibrant communities” implying that public housing communities are a problem, it is important that these stories be told.

Victorians don’t have to look far to get a glimpse of what happens when governments and developers “create communities” on public housing estates. After a large estate in Carlton was handed over to developers in 2005, public tenants were locked out of most of their own estate.

Dividing walls, separate entrances, car parks and private gardens built for the private apartment owners have made a mockery of claims that the developers would build integrated communities. A recently published study of the Carlton example, by Melbourne University academics Kate Shaw and Abdullahi Jama, found that the “social-mix approach to inner-city estate redevelopments in Australia is driven more by the imperative to capitalise on the sale of public land than it is to assist public tenants”. On the Carlton estate alone, developers have already taken in at least $300 million.

This government’s current plans are much more ambitious than anything tried in the past. There is the potential for many different groups to join together to fight back. Already, the Greens have publicly opposed the plans and helped to organise the Flemington rally. A number of local councils have passed motions against the redevelopment program. The next protest will be on Saturday, 4 November, at 1pm on the Walker Street estate in Northcote.