Most public housing in Australia is a monument to a different era, a time when governments built houses, just as they would schools and hospitals. Inconceivable to anyone born in the last 40 years, there was a period when the government was hungry for land to build things people could live in, not just drive on.

In Melbourne, dozens of beige concrete tower blocks erected on land acquired across the inner city are the most recognisable markers of this period – still known as commission flats, after the long defunct Housing Commission that had the job of building them. Less quintessential but more numerous are the low rise brick villages known as “walk up” estates. And there are houses, about 25,000 of them, often grouped in small pockets around the suburbs and in some regional towns.

All told, Victoria’s public housing stock numbers about 65,000. Today, it is ageing (60 percent is more than 30 years old) and often in poor condition (“seriously deteriorating” according to the Victorian auditor-general). Victoria is easily winning the race to the bottom on housing, with public housing making up a miserly 2.7 percent of all dwellings here, far less than the national average of 3.6 percent (which itself is at a 35-year low). This proportion has shrunk just about every year since the early ’80s. The reasons for this are as easy to see as the cranes climbing all over Melbourne’s skyline.

In the most recent decade past, between 2006 and 2016, Victoria’s population grew by 1.1 million people, or 22 percent. Most of these people found homes in its capital city, which is bulging with new residential construction. From the apartment blocks in the CBD to the expanding suburban fringe, Melbourne is one of the centres of what the Housing Industry Association describes as “the longest new home building cycle in [Australia’s] modern history”. Conspicuously absent from the building bonanza though is the government, which ended 2016 with around 581 fewer dwellings on its books than it started 2006 with.

It is difficult to overstate the degree to which neglect and inaction, for decades, have characterised the management of a social infrastructure that is key to providing for a need shared by every human, every day – the need for shelter. While successive governments have sat on their hands, property developers continue to swallow up land and choke on profits as Melbourne sinks deeper into a housing affordability crisis.

The statistics are well known; less than a half of one percent of private rental properties are affordable for a single person on a pension, and around 35,000 people are on the public housing waiting list. While they wait, these tens of thousands languish on couches, on the streets and in cheap motel rooms; they eke out their survival in houses they can’t afford, which are overcrowded or not fit for habitation. The government itself estimates that at least 70,000, and perhaps as many as 100,000, poor households are in fact eligible to be on the public housing waiting list.

In this context, a proposal to demolish multiple public housing estates across the city and give the land to property developers would surely be unfathomable to all but the most rabid of free market cranks. Well, it isn’t unfathomable to the Victorian Labor Party; it is policy – perversely named the Public Housing Renewal Program.

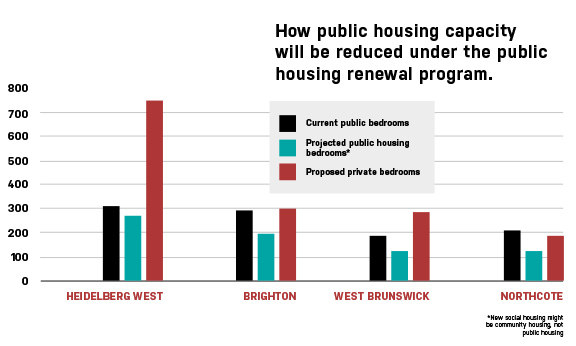

The “renewal program” is targeting an initial tranche of nine “walk up” estates in inner city suburbs like Northcote, Clifton Hill, North Melbourne, West Brunswick and Brighton. Under the plan, the existing public housing dwellings on the estates – about 1,000 of them – will be knocked down and the land cleared, at the government’s expense. The bulk of the land, wholly public and acquired specifically for public housing, will be sold on the cheap to developers who will build and sell thousands of private apartments on the estates – likely around 5,000. In “exchange” for getting a hold of the public land, the developers will be paid by the government to rebuild a fraction of the estates as social housing.

The Andrews government, of course, is not the first to have clocked that there are significant profits to be “unlocked” through the sale of public assets, including such a scarce resource as public housing. Similar privatisation plans have already been carried out controversially on estates in Kensington and Carlton. However, if successful, this government’s program would top them all as the biggest single sell-off of public housing in the state’s history. And it’s probably only the start.

The government wants to move quickly. Thousands of tenants living on the estates are now on the countdown to a mass eviction. Already, and while opposition mounts, the government is doorknocking houses to give residents relocation “agreements” that are being presented as a strictly no choice affair. It has budgeted $16 million (enough to build 53 new public housing dwellings) for staffing and other costs associated with the job of clearing public housing estates of public housing tenants.

Residents are being promised that they will be the first ones returning to their estates after the developers are done. The likelihood of this is slim indeed. The government knows this, and the developers are banking on it. For, while many thousands of new houses will be built on these estates (in some cases doubling or tripling the total number of dwellings), the majority of these will be privately owned.

Public tenants will find that the proportion of the estate that is social housing has shrunk significantly and will accommodate fewer people than before. On many estates, the loss of social housing capacity will be as much as a third. Across the first four estates for which planning documents have been made public, the number of three-bedroom homes fit for families will drop in number from 182 to 25 – a loss of 471 bedrooms. While the housing minister is pledging a “right of return” for displaced tenants, the question that no one in government can answer is: where will they go?

the government is also giving no guarantees that what remains of the social housing after the developers carve up the estates, will in fact be public housing. Instead, it appears most likely that these houses will be handed over to the community housing industry. The effect of this transfer, a politically palatable form of privatisation, is a loss of security and rights for any public tenant who can beat the odds to get back on their estate.

The Public Housing Renewal Program is shocking evidence of the lengths to which governments will go to avoid one of the obvious fixes for the deep and persistent housing affordability crisis – a large-scale mass public housing construction program. Around 3,500 new public housing dwellings every year for the next 20 years would need to be built just to bring Victoria close to the national average, to say nothing of what is needed to put a serious dent in the housing waiting list. But while the coffers for spending on police, roads and prisons are always full to the brim, hardly a penny can be found for housing, and 35,000 Victorians are paying the cost.

Steph is a member of the Public Housing Defence Network