The neoliberal model that has dominated mainstream politics and economics for decades is in crisis.

Popular discontent with the austerity and inequality that have resulted from the imposition of neoliberal policies has become a major question in world politics, with Brexit, Sanders, Trump and Corbyn each in their own way undermining the neoliberal consensus. Mass dissatisfaction has joined with the growing realisation by the managers of the capitalist system that neoliberal policies are incapable of dragging the world economy out of the rut in which it now finds itself 10 years after the onset of the global financial crisis.

The neoliberal revolution

The beginnings of the neoliberal project in the advanced countries can be dated to its last systemic crisis in the 1970s. The economic policies that had dominated in the postwar decades – Keynesian demand management to stabilise economic growth and profits, the promotion of “mixed economies” with a market sector buttressed by state ownership of core industries and an international trade system dominated by the US-centred fixed exchange rate regime – no longer seemed to work for the ruling class.

The most obvious indication of the crisis was the onset of chronic unemployment, inflation and slow growth. Alongside these, structural changes were eroding the foundations of the postwar set-up. These included rapid expansion of international trade, production, finance and banking alongside the growth of monopolies tied to international markets. Big companies once sheltered by state mechanisms and national markets now demanded from their governments tax cuts and the stripping away of regulations, to allow them to compete against their rivals based in other states. On top of these factors went falling profitability on capitalist investments – the bosses were no longer making money hand over fist.

Thatcherism and Reaganism, what would later be called neoliberalism, emerged in response to this crisis of the postwar order. They involved a wholesale attack on the working class: mass redundancies, work intensification, repression of trade unions and imposition of aggressive private sector corporate managerialism in the public sector; cutting minimum wages and lowering social assistance and social welfare; a greater emphasis on user pays in the provision of public services, education and health care; and a switch from progressive and direct taxation to regressive and indirect taxation.

As well as driving down the cost of labour, the neoliberal project also involved shifting capital out of sectors where it was only marginally profitable to areas where more money could be made – making capitalism leaner and meaner through privatisations, restructuring, slashing state subsidies to some sectors (while significantly expanding them for others), deregulating industries like the airlines, banks and telecommunications to allow the strong to gobble up the weak, and reducing restrictions on international trade and finance. The advent of advanced computers and information technology helped these processes by cheapening machinery and allowing the bosses to coordinate ever more extended divisions of labour across national borders.

By driving down the cost of labour and purging capital, the British and US governments were able to revive the rate of profit for the capitalist class. Western bosses got a further fillip with the arrival of China as an economic power, cheapening the cost of imported goods, depressing wages and providing new markets.

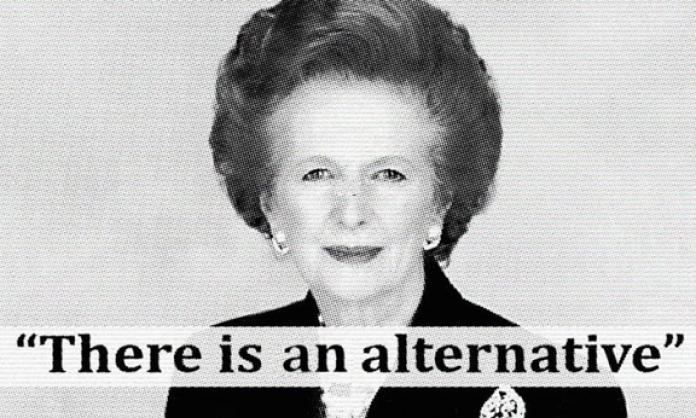

Thatcher and Reagan were quickly followed by governments across the OECD. The fall of the Berlin Wall transplanted neoliberalism wholesale into Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. India and South Africa also opened up their economies and sold off state industries. Governments of the left and right outbid each other in their enthusiasm for economic deregulation. Here in Australia, it was the Hawke and Keating Labor governments that led the way. In Britain, the Blair government simply took Thatcherism and gave it a new coat of paint. Across politics, the universities and the public service, Thatcher’s mantra “There is no alternative” (TINA) was embraced. Free market economics ruled triumphant. Politics was reduced to discussion of trivial points of product differentiation. The public, offered a suffocating political consensus by the major parties, switched off, and election participation sank to historic lows.

While there were differences from country to country, neoliberalism produced the same broad features across the board: the accumulation of massive fortunes in the hands of the few alongside, at best, only modest improvements in wages, at worst impoverishment and degradation. Hammer blows by governments and bosses pulverised trade unions, coverage rates falling to historic lows and strikes collapsing. Inequality, which had been on the decline for many decades, now shot up.

This agenda did not go unchallenged. From repeated general strikes in France to township protests in South Africa, from the anti-capitalist protests at Seattle and Genoa to the “pink tide” in Latin America, many people fought back on the streets and at the ballot box in the 1990s and 2000s. Governments responded by ramping up state repression and imposing ever tighter restrictions on the democratic voice. They also rallied to the defence of neoliberalism, urging their citizens to accept its even more intensive application.

While neoliberalism revived the rate of profit on investments, it did not make the system any less unstable. Ranging from Central and Latin America to Russia, to east and south-east Asia, right across to Wall Street, financial crises regularly ripped through the system, destroying livelihoods. Economic growth was slower in the 1990s and 2000s than it had been in the 1970s, while investment in productive industry stagnated. But fortunes were being made, and the ruling classes of the world appeared to be able to patch up the system when banks went bust and stock markets fell.

The global financial crisis

The global financial crisis of 2008 changed all of this. For a while it appeared as if the entire international financial order was on the brink of failure. International trade plummeted, and stock markets plunged. Rapid government intervention held off complete collapse, but neoliberal ideology was hit hard.

Everything that the politicians, professors and journalists had told their populations for two decades about the superiority of free markets turned out to be false. Free markets, it became clear, were responsible for the devastation of the world economy. The “experts” had failed to diagnose and treat the massive financial imbalances that had brought the system to its knees. What’s more, the bankers were all crooks. Former champions of neoliberalism issued mea culpas in the leading newspapers of the world.

But the ruling classes were able to salvage neoliberalism. Despite some heroic struggles – including the Arab revolutions of 2011, repeated general strikes and student protests against austerity in many European countries, along with the Occupy encampment in the heart of Wall Street – the working class and the left were not able to destroy neoliberalism from below.

Nor was neoliberalism destroyed from above. If the Great Depression of the 1930s created the conditions for Keynesianism and the crisis of the 1970s the conditions for neoliberalism, the global financial crisis produced no similar ideological revolution in the ranks of the ruling classes. After a sickening crunch in 2008, stock markets began to rally in 2009. Central banks drove down interest rates, pumped billions into the system, and the bank balances of the rich soared once again. The bosses breathed a big sigh of relief. Why worry about the long term future of the system if we’re still making money? Let the working class pay for the cost of dealing with the crisis – and so wave after wave of harsh austerity was unleashed by governments across the world, and living standards for the majority of the population sank.

The crisis deepens

Today, however, the chickens have come home to roost for neoliberalism. The Western liberal capitalist order has been severely shaken as dissatisfaction with neoliberalism has broken through in two of the centres of world politics, the US and UK.

The strong showing by both Sanders and Trump in the US presidential primaries last year was one sign that neoliberalism was in for a reckoning. Then in June, the Brexit referendum in Britain returned a shock result. Less than five months later, Trump won the US presidency, and in June this year, the success of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party repudiated the arguments of his opponents who said that a social democratic agenda could not win mass electoral support after decades of neoliberalism.

These are very different phenomena, but each in its own way was driven by widespread hostility to the neoliberal project. US writer Nancy Fraser has described the theme common to them all: “In every case, voters are saying ‘No!’ to the lethal combination of austerity, free trade, predatory debt and precarious, ill-paid work that characterize financialized capitalism today”. Inequality has become the lightning rod for popular discontent around the world.

With the credibility of the centre parties most identified with neoliberalism in tatters, stocks have risen for parties and individuals on both the left and the right. The far right has so far been the main beneficiary. This is obvious with Trump and his far right supporters, but their ilk have also done well in polls in Europe, scoring millions of votes and coming within centimetres of winning presidencies. In many cases parties of the centre have hung on only by stealing their opponents’ policies – racism in particular. The big far right demonstration in Poland in November was an indication of the right’s ability to get people out onto the streets. But the success of Sanders and Corbyn demonstrates the space for a left wing alternative as well. Even in Australia, which has escaped the worst of the economic crisis, there are distant echoes of this phenomenon, with the popular rejection of the Abbott government’s savage 2014 budget and the ALP’s decision to run hard on inequality.

It’s not just that the people are saying “Enough!”. While Wall Street may be at record highs, the more astute capitalists and those who oversee the system’s affairs – the central bankers, the OECD, the IMF etc. – are very aware how weak is the recovery in national output, investment and international trade. They know that they are living on borrowed time and that the next financial crash is not far away.

In the United States, this awareness of the fragility of the economic situation is combined with alarm about the country’s relative decline as the world’s only superpower. Challenges are arising on many fronts, but China represents an existential threat: a peer rival of similar economic clout, growing military capacity and an ideological framework very much at odds with that promoted by the US.

Trump’s economic nationalist project is one response to this problem: to rebuild the country’s manufacturing base using protectionism and government subsidies, along with a big boost to military orders. The architects of this project scorn the free trade agenda promoted by Hillary Clinton in 2016. In their view, neoliberalism only destroyed US industry and allowed China to come up on the inside lane.

Their solution is to intensify one element of neoliberalism – attacks on the working class and slashing environmental protections – while threatening another: the international trading system superintended for decades by the United States. Trump’s decision to walk away from the Trans Pacific Partnership – a multilateral trade agreement drafted by the Obama administration and a dozen US allies in the Asia-Pacific – is the clearest signal yet that it is no longer business as usual. Trump’s bellicose tweets attacking his opponents at home and abroad only reinforce the sense that the liberal capitalist order is being rocked from the top.

The future

If blows to neoliberalism are only too apparent, it is also important to point to underlying continuities. These include not just Trump’s enthusiasm for “soak the poor” tax “reform” but also the push back he has received from within the US state apparatus and Wall Street against some of his pledges to rip up existing US trade agreements. Many other ruling classes are also keen to prop up the system of international trade and finance from which they have benefited in recent decades, even if the Trump administration has gotten cold feet. The EU was shaken by the Brexit referendum but the project of closer European economic ties is still on track.

Much is uncertain. It is possible that neoliberalism can stagger on for years to come; it will not disappear of its own accord. Its future depends on the class forces at play, not just within the White House and broader administration, not just in the battles between rival ruling classes, but also in the struggle between the capitalists and the working class.

In the absence of successful resistance by the exploited, our rulers may come up with some modifications to the neoliberal project or even adopt a quite different one. But whichever path they follow, those who rule can prosper only at our expense. We can expect nothing from them other than the continuation of all the assaults we have endured in recent decades. Whether in the hands of the neoliberal centre or their far right opponents, we can also expect the same scapegoating of refugees, migrants and Muslims that have been used to divert our attention from their common agenda of austerity. It is up to our side to build an alternative to their common plans, and that means a fight on two fronts: a physical fight in the form of strikes and demonstrations to cripple the workings of their system; and an ideological struggle to advance the agenda of the left, which is the only basis on which the fight for a different world based on human need, not profit, can be waged.