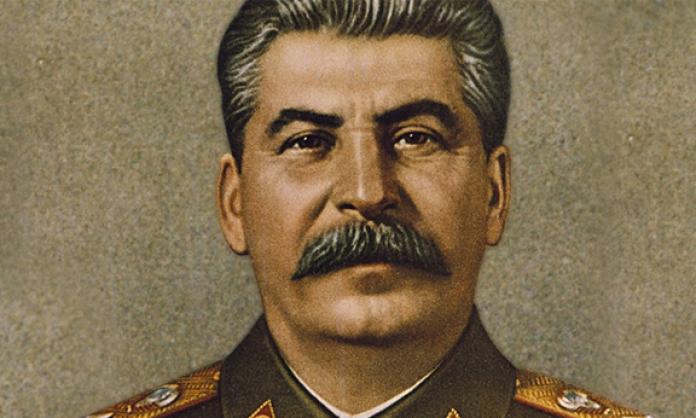

Stalinism is experiencing a small revival. For now, it is greatly exaggerated online, where many of the popular socialist meme pages are as devoted to praising gulags and North Korea’s nuclear missile program as they are to denouncing capitalism.

But as the imagery and politics of Stalinism are rehabilitated as an edgy alternative to liberalism, some real world would-be activists are falling for the old Stalinist orthodoxies as a political guide.

Stalinism, broadly defined, is the social system constructed in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s, the beliefs that justified it and the political parties that promoted it. It seemed to exhaust itself from 1989, when the Eastern Bloc collapsed and many of the Stalinist parties around the world dissolved or abandoned their pretence of socialist politics.

But now, with the distance of time, it can be easier for Stalinism to seem more attractive than it did in the immediate aftermath of its disintegration. Young Stalinists can now remember the attractive full-colour propaganda posters, the songs of the Red Army Choir and the McCarthyite red-baiting that seemed to confirm the subversive and radical characters of the pro-Stalin Communist parties.

It is little remembered that those Communist parties were often seen by most of the left and the workers’ movement as the most conservative, right wing and counter-revolutionary current in the broad left.

Ruling class politics

Stalin came to power after the defeat of the international revolutionary wave of 1917-23. As post-revolutionary Russia was besieged and encircled, the working class activists who had made the revolution vanished from the scene.

Many were killed by counter-revolutionary armies in the civil war; others starved or fled the cities in the famines that followed the blockade. With the working class in a state of political collapse, Soviet society was coordinated by an army of factory managers, bureaucrats and high state officials.

By the middle of the 1930s, the Russian Communist Party – which still claimed to be a revolutionary socialist party of the working class – was mostly made up of managers, army commanders and state bureaucrats. Stalin came to power as the leader of these managers and commanders. The Communist Party, in possession of state power, used its position to exploit and oppress the working class.

Under Stalin’s regime, workers were denied the right to bargain collectively. They required state permission to move from city to city. Workers who missed one day of work could be dismissed. Being dismissed, they could be evicted from their home. Resigning their job without permission left workers barred from future employment: if they worked in a military industry, they could be sent to prison for eight years. Strikes were described as “counter-revolutionary sabotage”, and strikers could face the death penalty.

Unsurprisingly, the Stalinist regime enforced gross inequality of the kind found in any capitalist society. Senior figures, like army marshals and high government officials, earned 100 times as much as the average worker (according to official Soviet figures).

Beneath the red flags and inspiring songs, society under Stalin became dominated by workplace managers and military commanders, with their needs enforced by police: a mirror of Western capitalism. The leaders of this society called it “actually existing socialism” and promoted their interests through the sympathising Communist parties around the world. Like any managers, they had much to fear from an international revolution.

Counter-revolution and fascism

Stalin, it is often said, defeated the Nazis in World War Two. The Nazis did inflict extraordinary destruction on the Russian population, before finally being defeated militarily. But during the decisive period in which Adolf Hitler came to power, the Stalin-affiliated German Communist Party was encouraged to do nothing, and to prevent the development of a unified working class anti-fascist movement. It is no exaggeration to say that the Stalinist influence on the German Communist Party allowed Hitler’s rise to power.

The Communist Party of Germany had, over the previous 10 years, been systematically meddled with by Stalin’s bureaucracy, “unreliable” leaders being driven out and tame bureaucrats installed in leading positions. By the time of Hitler, this formerly revolutionary party was a real “Stalinist” party of the classic type: it could be relied on to follow instructions from Russia without dissent.

At the end of the 1920s and beginning of the 1930s, one of the key concerns of Stalin and his German supporters was to prevent any German Communists from collaborating politically with non-Stalinist workers: any political authority that rivalled Stalin’s was a threat to the political power of the Russian managerial class.

This priority was far more important to the Stalinists than fighting the rising Nazi movement. Between 1928 and 1930, the Nazis increased their vote from 800,000 to 6.5 million. They were on a potential path to power, and workers were crying out for united action against fascists. But united, militant working class action would threaten Stalinist bosses, as it would threaten every other boss: so instead of raising the alarm and taking the lead, the German Stalinists encouraged complacency.

“The only victor … is the Communist party”, declared one of the German Stalinist leaders after Hitler’s party made significant electoral gains. “We are not afraid of the Fascist gentlemen. They will shoot their bolt quicker than any other government”, he declared in parliament.

When the rival, non-revolutionary Social Democratic Party proposed united action of all socialists against the fascists, the Communist Party declared this to be “the most serious danger that confronts the Communist Party”. Just over a year later, Hitler was in power and the German socialist movement was smashed. The Stalinists had achieved their goal: no rival ideas had been encountered by their German adherents. The price was the coming to power of Hitler, the Holocaust and World War Two.

Three years later, the Stalinist revulsion at working class power again helped fascists to power: this time in Spain, when, during the revolutionary civil war against the fascist general Francisco Franco, the Communist Party took the lead in breaking up the revolutionary working class movement in Catalonia, abolishing its militias and crushing its general strike.

In both Germany and Spain, the Stalinist regime – always prioritising its own class interests – paralysed and crushed workers’ organisations, just as they were entering life-and-death struggles with surging fascist movements. Like any other exploiting, ruling class, the Russian Stalinists were more interested in dominating humanity than in fighting fascism.

Conservative parties

Franz Borkenau, an Austrian writer who travelled to Spain, wrote that there, Stalinism was not really part of the workers’ movement: rather, it was “the extreme right wing” of the Republican (liberal) coalition. The Stalinist parties’ fear of independent working class organisation meant that from the 1930s to the 1960s, they increasingly came to be known as right wing political groups with nothing to offer radicals .

The US Communists of the 1930s declared themselves adherents of “Americanism” and worked hard during and after a huge strike wave, which threatened to reshape US politics, to ensure that the energy of workers was redirected into the Democratic Party.

During World War Two, the US Stalinists broke strikes, persecuted trade union militants and celebrated workplace speed-ups and pay restraint. “You can’t strike against the government”, declared famed Stalinist union leader Harry Bridges. By the 1960s, US Stalinists were praising the warmongering Democrat John F. Kennedy, even as the movement against the Vietnam War emerged.

Partly, this conservatism suited Stalin’s foreign policy – while he was alive. But it also emerged from the logic of Stalinism itself, which was to collaborate with bosses against the working class in Russia and around the world.

Much of the rebellion of the 1960s was directed against the right wing Communist parties, whose conservatism led to betrayals that shocked radicalising youth. A generation of young militants never forgave the French Communist Party for its role in sabotaging the great general strike of 1968. Stalinists there systematically wound down the explosion of factory occupations, discouraging workers from linking up with one another and driving that outburst of struggle directly into a great defeat.

Similarly vile betrayals gradually disintegrated most European Communist parties. The Communist Party of Australia advocated that trade unions suspend strikes and instead just campaign for the ALP. Demoralised and directionless, they dissolved themselves at the start of the 1990s.

Most of these betrayals have now been forgotten. Online Stalinists enthusiastically defend slave labour, gulags and the extermination of political opponents – perhaps because they seem subversive. But these methods have nothing to do with Marx’s conception of communism as an emancipated, classless society; they are the methods of exploiters and oppressors, which is why they went hand in hand with the right wing, class-collaborationist liberalism that the Stalinists would rather forget.