A new study published by the University of New South Wales highlights widespread wage theft and exploitation of migrant workers in Australia.

According to the report, Wage Theft in Silence, almost a third of temporary migrants earn $12 per hour or less – roughly half the legal minimum for casuals.

Senior law lecturers Bassina Farbenblum and Laurie Berg surveyed 4,322 migrants from 107 different countries. More than half the participants, or 2,250 workers, reported having been underpaid while working on a temporary visa in Australia.

Contrary to the assumption that migrant workers are unwilling to take action, the survey found that “well over half (54 percent) of underpaid survey participants had either already tried to recover wages (9 percent) or indicated they might try in the future (45 percent)”.

Unsurprisingly, “among those who had been a member of a trade union in Australia at some point, 28 percent of underpaid participants had tried or were planning to recover their wages, compared with 10 percent of underpaid participants who had never been a member of a trade union”.

The survey also dispelled the myth that migrants are ignorant about their entitlements. The vast majority receiving $15 or less per hour knew that the legal minimum wage was higher. The study also found that Asian participants were the most likely to want to recover stolen wages.

Nevertheless, only a small number – less than one in ten – had taken action to recover stolen wages.

Some of the most common reasons for this, according to the survey, involved the fear of being fired and/or potentially jeopardising their visas and risking deportation. And many migrants don’t believe they will recover wages, so it is not worth the risk.

The report found that this pessimism is justified: 3 percent of participants subject to wage theft contacted the Fair Work Ombudsman to recover their wages. Of those, only one-third received any reimbursement.

These findings were confirmed by Rizky, an Indonesian worker on a bridging visa who spoke to Red Flag about his experience picking fruit in Victoria.

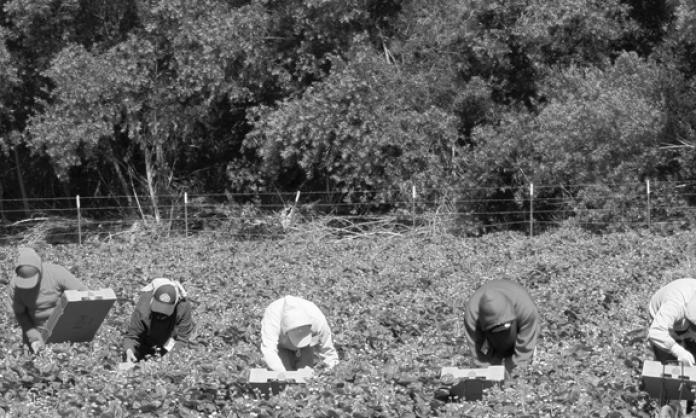

According to Rizky, fruit pickers endure 10-hour shifts exposed to blistering heat, sun, dust and wind. Rizky remembers picking tomatoes with particular displeasure:

“Because you have to crouch so low to the ground you will get back pain. The work was so hard that I could only do it for two or three days a week”.

None of the farms Rizky worked on provided basic amenities like water, toilets or break rooms. “If you need to go to the toilet, you find an empty row with no one else around and use that.”

These appalling conditions are accompanied by shockingly low wages. Working in the packing sheds or picking nectarines pays $15 to $17 per hour – $5 to $9 less than the legal minimum.

Other picking, however, is paid by the piece. Rizky struggled to make $150 from 10 hours picking cherries, and only $70 picking tomatoes.

Often it’s even less – one employer deducted a 15 percent “tax” from his pay, and others charge workers $10 per day for the drive to and from the farms.

Workers are also exposed to abuse and discrimination from supervisors, who “treat the European pickers differently from the Asian pickers. They would shout at us and abuse us, but not the Europeans”.

According to Rizky, farms even discriminate between nationalities. Workers on bridging visas (predominantly Asian) are paid lower piece rates than those on working holiday visas (predominantly European).

Tim Nelthorpe, a farmworker organiser for the National Union of Workers, estimates that 80 percent of horticultural workers are paid below the minimum wage.

“They use sham contractors to underpay a predominantly migrant workforce”, Tim told Red Flag. “The award is very weak, and most workers work for piece rates. I’ve seen wages of $5 to $15 per hour on a regular basis.”

According to Tim, “It’s not just small cash contractors that exploit their workers; the big employers do it as well. The vast majority of the industry is built around supplying to Coles and Woolworths, as well as export”.

Over the last three years, the union has made a serious effort to organise the horticultural industry in Victoria and South Australia. Previously there was no active union in the sector.

Although the insecure visa status and language barriers of farm workers have presented a challenge, Tim insists that “the techniques for organising are not new”.

“We’ve used tactics developed by the Wobblies [the Industrial Workers of the World] and others. We’ve had a real focus on activist development, and we’ve put in real time to develop workplace and community leaders.”

These efforts have begun to bear fruit. The union claims to have won hundreds of thousands of dollars in back pay for members, as well as pay rises of $10 per hour at several work sites.

The union has also eliminated cash contracting from some of the large vegetable farms and tomato glasshouses in the south-east of Melbourne and the northern suburbs of Adelaide.

Perhaps more importantly, union membership in the horticultural industry has doubled in the last year. More than 200 farm workers marched in last month’s Change the Rules rally in Melbourne, by far the largest National Union of Workers contingent.

“Workers in very precarious positions have been able to come together and fight for better pay and conditions”, says Tim. “They’ve had to fight against racial hierarchies, unsafe workplaces, sexual harassment and brutal anti-union activity, and all in an industry where they’ve had no support until recently.

“In this industry people assume that migrant workers and casual workers won’t stand up and that it’s impossible for them to organise. But if unions have patience and put the time into developing leaders and doing the hard work, then any industry is organisable.”

Rizky, who has a history of union organising in Indonesia, agrees. He first attended a union meeting in Shepparton last year, and joined the union soon after.

“The union helped me very much. You can’t fight by yourself, you have to organise to fight.”