Thirty years ago this month, Noongar activists set up a protest camp at Gooninup, the site of the derelict Old Swan Brewery on Perth’s foreshore. This marked the beginning of a four-year long struggle to secure recognition of an Aboriginal sacred site.

Aboriginal protesters and their supporters, including several WA unions, called for the demolition of the Old Swan Brewery and the creation of a park for all Perth residents to enjoy. The state government, mired in the corruption of the WA Inc scandal, was determined to allow WA’s biggest property developers to redevelop the site as an up-market bar and restaurant.

Gooninup, as it was known by the Whadjuk people of the Swan River plain, is a site of great Aboriginal significance. In Aboriginal Dreamtime, when the Waugul, an ancestral serpent that moved across the river plain, created the Swan River, Gooninup served as its resting place. It was used by Noongar people as a trading place and a site for rituals, camping and initiation.

Soon after British colonisers occupied the Swan River, a native institution was established, allegedly for their protection. However, Noongars were soon excluded from the site and it was turned into a flour mill, convict depot and tannery. In 1879, it was purchased by the Swan Brewery Company, the state’s major brewery, which occupied the site for a century.

Aboriginal people in Western Australia were forced off their lands; children were removed from their families and placed in state institutions. Between 1927 and 1954, under the notorious 1905 Act, Perth was declared a prohibited area to Aboriginal people. Much of Perth’s Swan River foreshore was off limits.

While the 1905 Act was repealed in 1963, stolen generations and stolen wages policies continued into the early 1970s, alongside discrimination and mass incarceration of Aboriginal people. Police unlawful detention and bashings of dozens of Aboriginal people at Laverton, in January 1975, and the police killing of 16-year-old John Pat in a Roebourne lockup in 1983, brought public attention to police brutality and Aboriginal deaths in custody, ultimately leading to a royal commission.

In this context, in the late 1970s, the Black Action Group was established in Perth, influenced by the politics of Black Power. Prominent in its leadership were Aboriginal Legal Service field officers Len Culbong and Rob Riley, and trade unionist Clarrie Isaacs. Culbong and Isaacs, also known as Yaluritja and Ishak Mohamad Haj, emerged as prominent leaders in the Swan Brewery dispute, alongside elders Ken Colbung and Robert Bropho, a leader of the Fringe Dweller community.

In 1978, the derelict and abandoned Old Swan Brewery was put up for sale; it was purchased in 1981 by property tycoon Alan Bond, as part of the Swan Brewery empire. Bond sold the brewery to Yossie Goldberg, who sold it to the WA Development Commission in a dodgy business deal later investigated by a royal commission.

Both Bond and Goldberg were caught up in the WA Inc scandal, each having donated generously to ALP coffers. Bond and his companies gave Labor premier Brian Burke and WA Labor more than $2 million in secret donations to facilitate his business ventures, while Goldberg donated $100,000 to a slush fund kept in cash in Burke’s office.

Redevelopment of the brewery was first mooted in 1986. Submitted proposals included a large tavern, restaurant, tearoom and multi-storey car park, much to the ire of local Noongar people. Opposition came from diverse quarters, including the Kings Park Board, the Brewery Action Group and even the state Liberal Party. In 1987, the government rezoned the site to allow development to proceed.

In 1988 – the bicentenary year – state planning minister Bob Pearce cynically proposed that the redeveloped site would become a “shrine to Aboriginal culture and heritage”, incorporating a museum to house “the best collection of Aboriginal art and artefacts in the world” and a performance space for Aboriginal groups alongside the tavern and restaurant originally proposed. However, no consultation took place with Aboriginal people, and the artefacts to be housed in the collection were sourced not from the local community but from the Northern Territory.

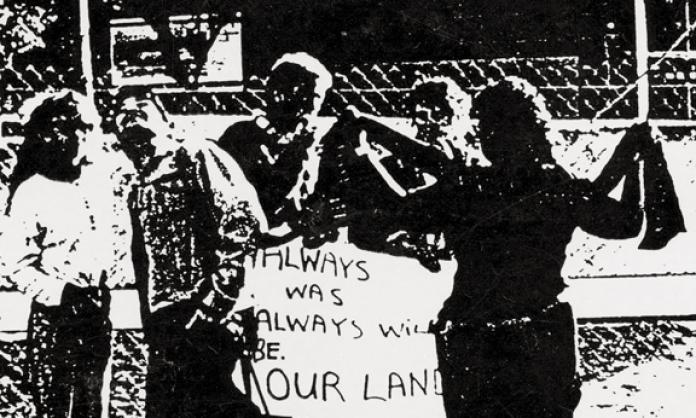

Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land

The Noongar community opposed the development from as early as 1978, when Ken Colbung called for the brewery to be demolished and replaced by riverside parklands. From 1986 onward, the Swan Valley Fringe Dwellers and other Indigenous groups appealed to state ministers for the brewery’s demolition and the preservation of the site as open space in acknowledgement of its Indigenous significance.

Legal actions followed. The courts ruled that the redevelopment plans were lawful: apparently the state government was not bound by its own Aboriginal heritage legislation. Aboriginal activists now turned to direct action.

On 3 January 1989, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people established a protest camp between Mounts Bay Road and Kings Park, opposite the brewery. Placards alerted motorists to the protest, declaring “Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land”. Like the Tent Embassy before it, the camp had its own mailbox and received a procession of visitors, including a delegation of Native Americans.

The protest engaged in several strategies, including appeals to the courts and machinery of government, and direct action. The Aboriginal Legal Service assisted representations to various Western Australian courts and the High Court in Canberra.

In April 1989, the federal government intervened, granting protection to the site under federal legislation. However, this was a short-lived victory: a deal between federal and state Labor allowed redevelopment to go ahead provided the state government legislated to make itself subject to its own Aboriginal Heritage Act. Once again, Labor threw Aboriginal people under a bus to satisfy the interests of corporate developers.

During the nine-month occupation of the site, trade unions emerged as crucial allies in the struggle. Most consistent were the Construction, Mining and Energy Union and the Electrical Trades Union, both voting to ban work on the site. Isaacs, a former president of the Water Supply Union and a state councillor of the Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union, was instrumental in forging alliances with the union movement.

The Builders Labourers Federation, then led by Kevin Reynolds, a right wing Labor ally of disgraced premier Burke, played a more ambivalent role. While declaring the union would ban work on the site if police attacked protesters, the BLF later went over to the government side, saying that the development would offer much needed employment for its members. This amounted to a brazen about-face from the BLF’s long tradition of green bans to save sites of historical and cultural significance.

Just like Noonkanbah

In 1989, I lived in university accommodation nearby. On 9 October, I awoke to a news broadcast on my clock radio. The brewery protest camp was being raided by police. I sprang out of bed and sprinted nearly three kilometres to the camp.

When I arrived, all hell had broken loose. Mounts Bay Road had been closed to traffic, and 100 police had descended on the site. I noticed a manual for the police operation sitting on the dashboard of an inspector’s car, demonstrating all the hallmarks of a carefully orchestrated attack on the right to protest.

By this time, protest leaders including Bropho, Isaacs and Culbong had been arrested. One protester said, “It was just like Noonkanbah” – a reference to the police operation that smashed a blockade of an oil drilling site on Aboriginal land in the Kimberley a decade before.

Belongings were strewn everywhere as police chased protesters off the site and confiscated their belongings. Those sent in to dismantle the camp to prepare for work on the site were declared “scabs” by unionists. Despite the continual arrival of reinforcements of protesters, the camp was no more. Bail conditions prevented protest leaders from returning to the site (though Robert Bropho returned in defiance).

In late 1990, a picket line prevented work on the site, supported by WA construction unions. The ETU and CFMEU – whose members were the backbone of the picket line – were threatened with deregistration by the Industrial Relations Commission if they didn’t lift their bans. In a setback for the campaign, a CFMEU membership meeting narrowly voted in favour of lifting the bans, 278 to 243. But a community picket line was maintained despite losing official trade union support.

Over the following year, the struggle continued. A petition gathered 30,000 signatures. The state museum’s Aboriginal Cultural Materials Committee declared its opposition to redevelopment. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission called for the brewery’s demolition. Then the state’s Legislative Assembly voted likewise. Yet the state Labor government, now led by premier Carmen Lawrence, thumbed its nose at all of them.

In June 1992, the state government’s newly appointed Heritage Council gave permanent heritage protection to the brewery. The following month, Lawrence and Aboriginal Affairs minister Jim McGinty signed a contract with John Roberts, CEO of construction giant Multiplex and another key figure in the WA Inc scandal. Roberts, who had donated $600,000 to WA Labor in the 1980s, could redevelop the site while paying a peppercorn rental.

Three thousand protesters assembled at the brewery site after the announcement was made. A rally outside state parliament was told the Liberal Party would demolish the brewery if elected in the coming state election, a promise it promptly reneged on after taking office in February 1993.

The climax came on 26 August 1992. After a 500-strong picket the day before, police arrived in force to break the picket line. Protesters were dragged from the gates of the construction site as trucks entered. More protesters were dragged away as they lay down in front of trucks. Running battles with police ensued as police escorted scabs onto the site. In a classic divide and rule strategy, Multiplex and Kalgoorlie MLA Graeme Campbell bussed in paid Aboriginal counter-protesters from Kalgoorlie and other country towns.

The following year, Liberal premier Richard Court took office. Following in the footsteps of his father, former state premier Charlie Court, he forged close relationships with the state’s all-powerful mining lobby, riding roughshod over Aboriginal demands for land rights. Court threw his support behind Multiplex’s brewery redevelopment.

As historian Charlie Fox observed in the compilation Radical Perth, Militant Fremantle:

“Perth got a redeveloped Brewery, transformed into flash restaurants and million-dollar apartments, a standing monument to WA Inc. Aboriginal people got nothing. Probably the only winner was John Roberts and Multiplex, which stood to make buckets of money from the redevelopment.”

However, the Swan Brewery dispute marked a watershed moment in struggle for land rights in the Perth region. Bropho fought hard to establish a permanent site for the Swan Valley Noongar Community in 1994, after more than a decade of occupation of the Lockridge town camp. In 1996, Isaacs toured the country alongside socialist Reihana Mohideen as part of a “justice tour”, roundly condemning the racist scapegoating of migrants and Indigenous people by then prime minister John Howard and newly elected federal parliamentarian Pauline Hanson. Isaacs was a vocal opponent of the native title regime, recognising it as a sham for Aboriginal people.