On paper, this was the most consequential federal election since 1993. Unlike what we have come to expect – each party claiming the “fiscally conservative” mantle and fighting it out over refugees and migrants – this poll was fought much more on economic terrain. The difference between the Coalition and Labor was somewhere between $250 billion and $380 billion. That’s the ten-year difference in government revenues, based on their stated policies.

The ALP had a plan to hit high income earners and pump tens of billions into dental and child care, universal preschool for three- and four-year-olds, cancer treatment, technical education fee waivers and wage subsidies for childcare workers. Modelling by the Australian National University’s Centre for Social Research and Methods estimated that the top 10 percent of households would have been almost $12,000 worse off per year under Labor (compared with the Coalition) – a hit of 4.7 percent of their disposable income. The top 20 percent would have paid for 70 percent of the ALP’s plan.

“Only the naive believe the battle between the classes ever ended, but in this election it’s more in-your-face than any time since the days of Labor’s Arthur Calwell”, Sydney Morning Herald economics editor Ross Gittins wrote, with a little exaggeration, three days out from the poll. “Bill Shorten and Chris Bowen plan to use both sides of the budget to affect the biggest redistribution of income from high income-earners to low and middle income-earners we’ve seen in ages.”

At times, this was a breath of fresh air in an otherwise low energy campaign. On paper, it should have been a winner. Melbourne-based think tank Per Capita, in its 2018 Tax Survey, found that two-thirds of people believe high income earners don’t pay enough tax and that almost three-quarters want the government to spend more on public services. The 21st ANU poll of social attitudes, conducted in 2016, found, consistent with previous polling, that about 55 percent of people prefer more spending on social services rather than tax cuts. “Asked if the government had to choose between higher taxes or lower spending on social services, 54 per cent of those polled favoured higher taxes”, the report further noted.

Yet the Labor Party’s primary vote in current counting is the second lowest since 1934 (when former New South Wales Labor premier Jack Lang had split from the party and took one-third of the vote with him). Against a divided government with no coherent narrative limping from one idiotic scheme to the next – a mean, reactionary organisation filled with bigoted culture warriors, anti-union hatchets and climate change deniers only tepidly backed by an unenthused bourgeoisie – the ALP fell flat. How do we explain this? While it is too early to assess all the specific factors, some things stand out.

**********

For all its talk about challenging “the big end of town”, the ALP was not poised to launch an assault on capital had it won office. It opposed the government’s proposed tax cuts for big companies but, overwhelmingly, Labor’s program hit the upper middle classes and a section of better-off workers. While its policies were progressive and supportable, they ended up being a shackle rather than an inspired call to arms.

For example, the Per Capita survey found that tackling corporate tax avoidance is by far the most popular option to pay for better services. Labor’s other measures enjoyed far less support and required more economic literacy to understand. By primarily going after middle class tax concessions to fund its spending promises, Labor was in a battle to cut through with its messaging: it’s likely much harder to mobilise sentiment against “franking credit cash refunds for SMSFs”, which no-one really knows the what fors, than to galvanise people behind a full assault on bank super-profits and the corporate retailers ripping us off on gas and electricity bills. In this way, Labor’s reluctance to pick a fight with big capital arguably (and ironically, given the perpetual line that we all have to be moderate to win) left the party more, rather than less vulnerable.

It also made the ALP more susceptible to the Liberal scare campaign that mobilised wealthy retirees and small property investors who collectively milk the public purse to the tune of billions each year. While the Murdoch press acted as a megaphone for every gathering of disgruntled investors, Labor never really hit back at these entitled brats either, leaving its campaign feeling lacklustre. “I’ve never seen an electorate which is quite so disengaged with the whole process”, veteran ABC analyst Antony Green told News Breakfast three days out from the poll.

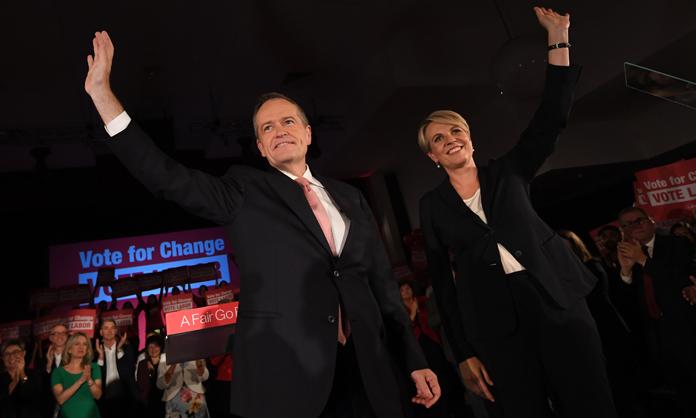

But the lack of support was not all about the ALP’s targets. Outside of the real and welcome boost to the “social wage” – the promised increased spending on social services – Labor was not proposing a major lift in working class living standards. The ANU modelling showed that the great “redistribution” would have lowered the disposable income of the poorest 40 percent of households by up to $246 a year. Those in the middle income brackets would have been hit between $500 and $1,200 per year. True, party leader Bill Shorten promised to reintroduce penalty rates for 700,000 workers. And the social wage gains and personal income tax cuts may well have more than compensated for other hits. But had Labor articulated a more radical program to lift living standards and create jobs, it might have won back and energised some of its historic base. On this front again, the problem wasn’t being too bold, but not bold enough.

**********

The long term decomposition of the ALP underpins this dramatic electoral failure and helps to explain the party’s inability to pull behind it more than about 40 percent of working class voters. Those opining that Labor frightened the horses and now needs to moderate its messaging are ignoring that “moderate Labor” – the politics of Liberal-lite – has been a dismal failure.

The suffocating technocratic consensus-building model embraced by a leadership that rejects struggle and conflict has strangled the only thing that can keep a membership party alive: a spirited rank and file. In truth, the ALP is a shell of its former self. Its membership as a proportion of the population is half that of 50 years ago. It struggles to staff polling booths on election day, many volunteers helping out as a favour to a friend alongside ageing true believers and students intent on a career in the apparatus.

And while the party bureaucracy speaks dewy-eyed about Chifley’s light on the hill, you will encounter few workers proselytising about Labor’s “great objective”. That’s because the experience of Labor in government, since treasurer Bill Hayden’s “horror budget” in the final moments of the Whitlam administration, has been corporatism. The leadership and ranks seem unaware that the vehicle they inhabit feels like a limousine passing us by rather than a bus carrying us all up the road.

While this electoral defeat is one for the ages, Labor’s primary vote has been in secular decline since Bob Hawke took over the leadership in 1983. It now seems fitting that today’s leadership engages in hagiography of the past leader. They describe Hawke as a working class hero. But many will never forget that he was an architect of one of the greatest transfers of wealth from workers to bosses in Australian history and played a leading hand in destroying rank and file unionism. Lauded by the party and the Murdoch press today, he was wildly unpopular by the end of his prime ministership (a satisfaction rating of just 27 percent, according to Newspoll).

On the other hand, many don’t remember that history or are unaware of it. And there may well be a layer of the working class who are the true children of Hawke: less class conscious, more individually aspirational and more inclined to be moved by visions of a “stakeholder society” in which each can rise above their lot than by appeals to solidarity. I wouldn’t try to quantify such a layer, but it would be truly ironic if the ALP’s stated successes in “modernising” Australia and being a “party of government” have contributed to undermining social democracy and therefore its own electoral prospects in this way.

Either way, the legacies of successive Labor leaders, Keating, Rudd and Gillard, have alienated wide layers of workers, many of whom have dabbled with other electoral dead ends led by people with a desire to lift, not the working class, but only themselves. And while the rusted-on Labor voter remains, a generational gap has opened. Young people today are far less committed to any single party than their grandparents are. As those elders pass, perhaps we can expect more volatility and one-term wonders.

An organisation anchored by the trade union bureaucracy does not drift quietly into the night. But Labor needs at least the perception of a major break from its past to live down its appalling legacy. Shorten was the opposite of that. No doubt the party will be back with a shiny New Leader™, but a social radicalisation and upturn in working class struggle is the only thing that could revive it for more than a year or two.

For the time being, we need not cry for the party. We have to organise against this rotten government. For all its triumphalism, on current counting the Coalition has registered its worst primary vote result since 1946, the first year Robert Menzies’ new party contested the federal election. It starts its third term as it ended its second: incredibly mean, but weak, divided and lacking much authority. There are wells of disaffection, which the ALP only half-heartedly was prepared to connect with. The task for the rest of us is to keep building an alternative prepared to stand up and start swinging.