Ian “Jammo” Jamieson lived and worked in the mining town of Rosebery on the west coast of Tasmania in the 1980s. It was a town in which workers were well organised, and had bosses and governments alike running scared. He spoke to Red Flag’s Alexis Vassiley. Transcription by Rebecca Hynek.

Can you describe the Rosebery mine?

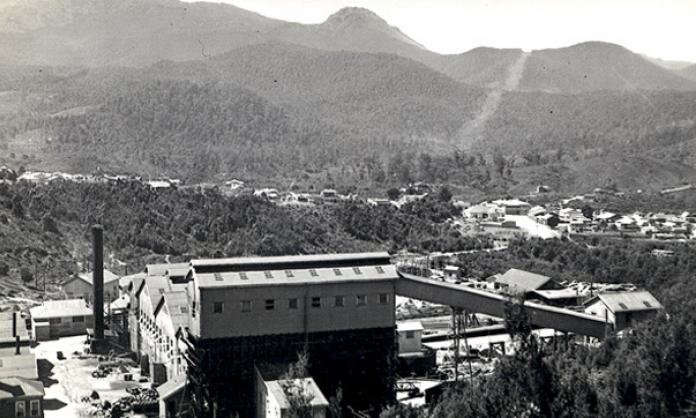

The Rosebery silver, lead, zinc and gold mine is an underground mine, one of a number on the west coast. During the 1980s, mining accounted for around 40 percent of Tasmania’s wealth. The west coast’s population was around 8,500, and more than 2,500 lived in Rosebery. Nearly 1,000 people worked in the mine and the mill.

The mine I worked in was very deep and old. They’ve evolved more modern techniques now. We used “panthers” – air-driven drills. When we took on the state government, a cartoon in the Hobart Mercury had a miner using the panther to get into the cabinet room.

How were you organised?

I was in the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU). It represented not only the miners but also the workers in the mill. We were the strongest union there, but with the Combined Union Council (CUC), we made sure that the AWU didn’t dominate. The CUC consisted of two formal elected delegates from each union. But then anyone who was involved, whether they were delegates on the job or just in a union – people could come along to meetings and participate.

What issues did you campaign about?

The basic issues that unions everywhere face – wages and conditions. At that time there was a bonus for miners; if they worked harder and faster, they could get a little bit more. We managed to get a bonus system that was of benefit to everyone, including the ground support crew.

Before our campaign, miners were the cream of the crop, and people who worked in the mills got the leftovers. Everyone agreed we had to make sure that everyone gets an equal crack at it. We also managed to get a shorter working week, 36 hours with one day off a fortnight.

What action did you take to change the bonus system and win the shorter hours?

By the time I got there, they were very strong and had won a big battle in 1983. In 1983, Rosebery miners organised a picket for 24 hours a day, seven hours away from home in the middle of winter, when it was snowing, and the boss really felt it.

The Socialist Workers Party comrades had established a very good union apparatus. When I first got there, there was a strike on in support of the nearby Que River miners. People were getting exhausted, so we had to make a decision to give them solidarity but to get back to work ourselves. So we made a levy to support them staying out on the grass.

There were a lot of strikes or go-slows and a whole range of different things we used to put the pressure on the company.

When the Liberal state government of Robin Gray tried to attack workers’ compensation, we organised a mass protest inside state parliament. At five or six o’clock one night we found out it was going to be debated first thing the next morning. We did a ring-around of people in Rosebery, sweating over whether enough people would turn up the next morning. And they did – about 100 people turned up. They drove for hours, overnight in winter. We all sat in a gallery of parliament house and it just frightened the shit out of the Legislative Council. And they voted against the government’s recommendations on workers’ compensation. So we won that issue.

Tell me about the AWU grassroots leadership.

I was on the union executive; we had a president, secretary and treasurer. We had nicknames. Lenny Blair, a big solid sort of guy, was the Enforcer. I was named the Tactician and the other guy was named the Priest [laughs].

And you worked out tactics for the strikes and campaigns?

Yeah – things like what we should be doing underground with the bonus campaign. How we should take on the Trades and Labour Council when they really hated us kicking up a stink about the workers’ compensation issue for instance. How to handle the various union officials that kept trying to muscle their way in. The hospital campaign [see below]. All those sorts of things.

Who had more power, you or the boss?

In the end the boss was always in control, but we certainly stopped them getting away with certain things. Safety was a big issue that we pushed very hard. Mining is a notoriously bad industry. I’ve seen terrible accidents. And people that because of the isolation committed suicide. After I left, there were a couple of mates of mine who were killed. One was a diamond driller on the surface boring down trying to find out where the ore body was extending but the pump blew up in his face and took his face off.

Which is why the workers’ compensation is so important ...

Extremely important. There were horrific accidents there that we would have suffered from if we didn’t fight hard against the workers’ compensation changes that Gray introduced.

How did you get on with the officials in the AWU?

In essence we didn’t. There was always ill feeling between the rank and file miners in Rosebery and the officials. My first big clash was over the Workers’ Compensation Act. The officials really ratted on us and agreed to accept Gray’s changes. We really made it very, very clear that we weren’t going to accept that. We sent down a delegation of miners to meet with them in Hobart and it was fractious.

The AWU officials weren’t allowed in town. Particularly the AWU industrial relations officer, a guy called Des Hanlon. He came a couple of times to try to convince us on the workers’ compensation issue. He actually voted against us in the Trades and Labour Council. We said, “Never come back. We don’t want you officials up here”. Hanlon disappeared and never came back.

What were some of the issues you took up that weren’t strictly industrial?

The biggest one was the Labor-Green government of Michael Field trying to close down the Rosebery hospital. It would have been disastrous. Lots of mining towns relied on our hospital. “Oh, it’s old”, they said. “Well then, build a new one” was our approach.

When we heard about the proposed closure from the nurses, we called a meeting of the Combined Union Council and decided from there to call a mass meeting in town so we could get everyone involved in the campaign. We wanted to involve the nurses as well as mobilising the industrial muscle of the miners and the mill workers. The matron of the hospital and quite a number of the nursing staff were brilliant. The community were up in arms.

We set up a Save the Hospital Committee which involved the unions as well as women in the community. We toured the west coast arguing to people that our hospital is first, but they’ll close yours down next. We got enormous support. The west coast was always being excluded from decisions about its future, despite producing Tasmania’s wealth.

We organised a rally in Hobart and we got over 2,000 people to come. It was a massive logistical task. We had this massive rally in Hobart and we also drove miners’ claims into Parliament House. We hired a caravan and I sat in the caravan – the “Miners’ Embassy” – for a week.

We won. The old hospital wasn’t pulled down, and a new hospital was built.

You used to do “inductions” for police officers, didn’t you?

The union was so strong. If there was any trouble in town, people would approach the union to sort it out, including issues to do with policing [laughs]. We had a new copper turn up and start booking people for parking violations, being a foot over the bloody parking spot on the main street. People were furious – they’d never gotten parking fines in their life. I was asked if I could do something about this new copper. So I said to the sergeant, “Tell him not to fuckin’ book people”. “Oh Jammo”, he says, “there he is over there out of uniform”. So I spent about a quarter of an hour lecturing him along the lines of, “You come into a mining community, you want to fucking survive you don’t be so bloody stupid as booking people for parking” [laughs]. Anyway, this guy said, “Oh I’m just the new fishing inspector”. Of course everybody roared laughing.

The union would even sort out issues like transport for people who needed to get out of town, as there was no public transport. It doesn’t sound much, but problems like that were always coming up.

How did your time in Rosebery end?

Mass redundancies came in the early 1990s, and three or four mines on the west coast were unable to stop them. My brother was killed in a car accident in Launceston on the Monday and they called me up and pulled me out of work. I drove up to Launceston and came back on the Wednesday. On the way back I heard on the car radio there were going to be massive redundancies on the west coast. I couldn’t do a thing about it because I had to get my brother’s body back to Melbourne, where the family was. By the time I got back into town, quite a few had already left. They’d gotten rid of about a hundred miners in Rosebery, including me.

What challenges did you face doing union organising as an openly revolutionary socialist?

People knew that I was a socialist. It’s part of my being and it’s probably why a lot of people in the union supported me. “There’s someone who will stand up for their beliefs and won’t back off and he’s fighting for us” was the feeling, even if they didn’t necessarily always agree with what I had to say. They would always defend my right to say it.

People knew that I was sympathetic to the environment because of the Franklin Dam dispute, which put a few people off, but when you start fighting for hospitals and other issues like that, those differences begin to fade.

I stood two or three times for state parliament and got 13 percent of the vote from among the mining communities. I also stood for the seat of Lyons as a member of the Socialist Workers Party. Eventually I was elected onto the west coast local council.

The backlash [for being a socialist] I got was from the government, the boss and from my own union officials. They were the ones that were white-anting, red-baiting, and eventually blacklisted me. But not the people I was working with and fought with in the community.

What do you think was key to your successes as a leader?

Listening to people and involving them as much as possible in a fight. It’s no good going up to the boss with cap in hand saying please do this. You need 200 or 300 miners behind your back.

And making sure people felt confident in what they were doing. Whether it was taking on the boss, taking on a union official. The big demonstration down in Hobart increased people’s confidence enormously. Making people think independently and as part of a class. And always taking things back to a mass meeting if you could.

Anything you’d like to add?

There is a poem by Marie Pitt called “The Keening”. It’s a really powerful poem about how the bosses are bastards. It goes:

We are the women and children

Of the men that mined for gold:

Heavy are we with sorrow,

Heavy as heart can hold;

Galled are we with injustice,

Sick to the soul of loss –

Husbands and sons and brothers

Slain for the yellow dross!

We did a play based very roughly on it and got the whole town involved. We got $13,000 off the government to put it on and [laughs] in the end we call for a general strike ... it was bloody good actually. There were about 100 people involved who had never before been involved in something like that! We got costumes made up, it was bloody good.