Stonewall! The iconic 1969 riot, which involved lesbians, trans, gays and street kids – black and white – fighting back one hot summer’s night in June against one too many cop raids on New York’s Stonewall Inn. It seemed just another night of raids like so many before: police dragging people out, beating up a few, hauling others down to the police station to be charged. But this time, a drag queen hit a cop, a lesbian resisted being thrown into the paddy wagon and the resistance took off. Bottles, stones, garbage bins, whatever people could lay their hands on was thrown at the police. There were all-out brawls. One protester told the BBC, “We were finally fighting back, it was exhilarating!”

It might have ended there. There had been demonstrations, sit-ins and a few near riots before. The events at Stonewall might have been just another episode like others before. This time they weren’t. As women’s liberationist Martha Shelley explained to the BBC, “The riots would’ve done nothing if we hadn’t organised afterwards”.

One young man, Mark Segal, who was newly arrived from Philadelphia, was handed a different sort of weapon to the bricks and bottles: a piece of chalk. With hurried instructions from friend Marty Robinson, he headed off down the streets around Stonewall, chalking just three words – “Tomorrow night Stonewall”. And they came back the next night and the night after that.

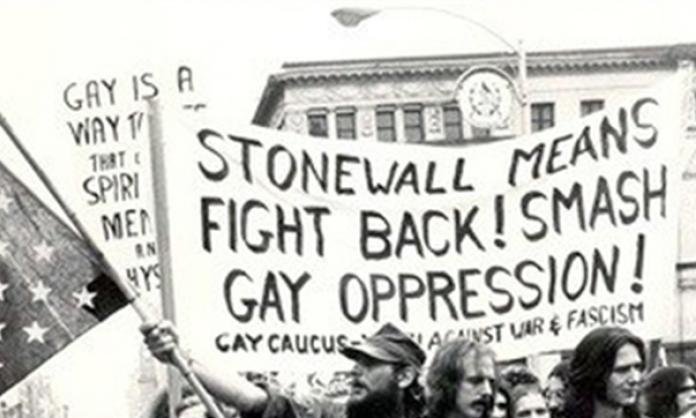

This was the high point of the militant 1960s, when workers were on the rise and the radical black and women’s liberation movements were on the streets demanding their rights. LGBTI people took note, adopting a similarly aggressive strategy oriented to the streets and willing to be disruptive in pursuit of, not just acceptance, but liberation.

Within days of the Stonewall riot, Robinson and other left wing activists formed the first Gay Liberation Front – taking the name to mark solidarity with the Vietnamese National Liberation Front.

The impact of Stonewall was felt as far away as Australia. Inspired by events in the US, gay liberationists here hit the streets. They “zapped” psychiatrists, held kiss-ins and mobilised hundreds to regular protests. The first was in in July 1972 against the ABC, which had refused to run a review of Denis Altman’s groundbreaking book Homosexual. In Melbourne protesters gathered outside ABC headquarters, followed by a similar action in Sydney, which became the site of the first arrest for LGBTI activism in Australia.

Sydney’s first Mardi Gras was held to celebrate the ninth anniversary of the Stonewall riot, and to show solidarity with LGBTI people in the US, who were then under renewed attack. The cops brutally attacked the procession, beating people up, arresting and charging 53 people. Two days later another 13 were arrested at the protest outside the courts. A huge protest march in August resulted in another 104 arrests.

Again and again, though, activists hit the streets determined to win their rights.

Many of these LGBTI activists came from the organised left and connected LGBTI oppression with a broader radical critique of society. Denis Altman expressed a widely held sensibility, writing in the La Trobe University student paper at the time “Gay Liberation sees with Marx that the liberation of each depends on the liberation of all”.

**********

Homosexuality had started to be talked about more openly in the 1950s, albeit negatively. NSW police commissioner Colin Delaney claimed it was a greater threat to society than communism, and successfully pushed the state government to introduce new homosexual crimes.

Such repression, as historian Gary Wotherspoon points out, often had the opposite of the intended effect in the long run, encouraging more questions about social mores. It led to a push for decriminalisation in which Communist Party member Laurie Collinson attempted to set up a homosexual law reform group in 1958.

While the activism of the 1950s was critical in laying the basis for the later decades, the 1960s changed everything for the left in Australia – as they did around the world. People took to the streets, striking, protesting war, resisting oppression, fighting for national liberation and joining left wing organisations to fight for a socialist world.

And it was in all these areas that young lesbians and gay men could be found – marching on the streets against the Vietnam War, for black and women’s liberation, on the campuses, amongst the young militant workers – demanding fundamental change. They naturally began to ask themselves, why aren’t we also marching for our own liberation?

In Lance Gowland’s story, we see some of this early activism. Lance was based in the NSW town of Goulburn and secretary of the Goulburn Trades and Labour Council. He’d been in the Communist Party’s youth group and then joined the party. In the late 1960s he got a gay rights group going in Goulburn. But, he told Sydney’s Gay Pride Group, “The police were on to us and they were parked outside when we had meetings and they were raiding our homes”.

He remembers that he and others were also against the US invasion of Vietnam, and now, as gays, wanted to be part of “the great upwelling of the social movement struggle”. So in 1970 he moved to Sydney “’cos everything was happening there”. He became one of the prime movers in the Communist Party’s development of its gay liberation policy and strategy.

In the 1970s, newly formed Trotskyist groups together with the Communist Party pushed for mass actions, a public stand in support of LGBTI people and union involvement. Most important was organising amongst workers, changing attitudes, getting anti-discrimination laws in place and taking action to back them up. Gay worker and supporter contingents marched on May Day in the 1980s, as well as in the anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Two unions in particular, both in NSW, stand out in their support of LGBTI rights in the 1970s – the Teachers Federation (now the AEU) and the Builders Labourers Federation (now the CFMMEU). They were the first unions and some of the first organisations of any type to take a stand for LGBTI people in Australia.

In 1973 and 1974, the BLF threatened to ban construction at Macquarie University to support students Jeremy Fisher and Penny Short, who were facing homophobic discrimination by the university administration. When Jeremy Fisher turned to the Macquarie Student Union for help, the left there knew who to call – the BLF. This union was headed up by communists, including people like Jack Mundey.

Communist influence in the Teachers Union was likewise critical in the campaign to defend Penny Short, who was stripped of her teacher’s scholarship on the grounds of not being a “fit and proper” person because she wrote an explicitly lesbian-themed poem for the student paper.

It was the adoption by the party of policy supporting liberation for gays that gave the teachers and BLF officials the political arguments to raise the issues – and win support – in the workplace.

After fragmentation of the movement during 1973 and 1974, arising partly from a turn to identity politics, a new layer of organised left wing activists revived activism in the second half of the 1970s. Leading the peak student body, the Australian Union of Students, they campaigned and won overwhelming campus support for gay rights.

In 1978 it was socialists Ken Davis and Annie Taylor’s swift response to calls for international solidarity with Stonewall that led to a day of action on 24 June, which led to the first Mardi Gras as well as other protests.

The early gay liberation movement had promised revolution – and along the way we had our riot – but 1978 was its swan song, and it collapsed soon after. In his book A Sydney Gaze, Craig Johnston, a leading activist and Communist Party member, summarised the process as changing the political framework from “Oppression to Discrimination, from Liberation to Rights and from Movement to Community”. While it didn’t mean the end of gay activism, revolution was no longer “in the air” as it had been, and the focus from the late 1970s onwards was increasingly on reform. Campaigns, such as homosexual law reform, were mostly state based, limiting the potential for nationwide action. In the 1980s, the devastating AIDS epidemic swept through. and activists focussed more on liaising with governments and the health professions to ensure non-discriminatory health care.

Meanwhile, the ALP was driving through the Accord, an agreement between unions and government that promised continued rising living standards for workers but delivered the opposite. Solidarity between workers was broken down, rank and file organisation smashed and union politics shifted to the right. Neoliberal attacks by the Labor government added to the devastation. Under these conditions, many of the gains of the 1960s were driven back.

More broadly, the ruling class was on the attack, and there was a worldwide downturn in political and industrial activity. The revolution had been postponed.

None of this can take away from the real gains of gay liberation – and the role of the left in founding and building such a liberation movement. Stonewall was not the first LGBTI riot in the US, but it was the first to turn into a liberation movement. Organised socialists played an important role, both because of their commitment to building an ongoing fight and through the political perspective they offered: that reform was not enough and that the revolutionary struggle to overthrow capitalism and win a socialist society was necessary to achieve sexual liberation.

This movement was transformational. It changed lives with its unapologetic defiance and the sense of pride it encouraged. As Marth Shelley wrote in Gay is Good, “We are shaking off the chains of self-hatred and marching on your citadels of repression”.

In Australia, as elsewhere, the movement – and the activists who built it – made it possible for people to live, work and love more freely. Discrimination and oppression still exist, because the movement’s revolutionary vision was never realised, but gay liberation nevertheless inspired people to keep fighting, through the AIDS crisis and more recently for marriage equality, in defence of Safe Schools and for trans rights.

Radical action, including riots and revolutions, have consistently opened up space for greater sexual freedom. As far back as 1789, the great French Revolution led to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in a number of European countries, and the 1917 Russian Revolution brought about changes in relation to sexual and personal life that are progressive even by today’s standards. As the young revolutionary Frederick Engels noted in 1894, “a phenomenon common to all times of great agitation ... [is that] the traditional bonds of sexual relations, like all fetters, are shaken off.”

When the formerly powerless develop a sense of their power, no aspect of society’s norms escapes questioning. In 150 Million, a tribute to the Russian revolution’s participants, Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky captures the spirit:

We will smash the old world

wildly

we will thunder

a new myth over the world.

We will trample the fence

of time beneath our feet.

...

a thousand rainbows will shake the sky.

Liberation is as relevant and necessary today as it was over 100 years ago. The struggle of LGBTI people for freedom continues to be bound up with the struggle against all injustice and oppression.