“We were supposed to be evolving, and the millennium was only a question of time. And what happened? It was found that instead of being perfect, civilization was turned into a shambles. What an interruption to theories and optimistic fantasies. Heaven was to arrive – and lo, it was hell that came!”

– Presbyterian Messenger, late 1919

The Spanish flu, which devastated the world in several waves between 1918 and 1920, was not particularly Spanish. In fact, it likely originated in the US. The first record of the condition was in an April 1918 public health report informing officials of 18 severe cases and three deaths in Haskell, Kansas. By May, hundreds of thousands of US soldiers had sailed across the Atlantic, spreading the deadly flu across Europe and into Africa and Asia. It was not the illness’s origin that gave it its title, but the response of authorities to the disaster.

The authors of a 2005 paper delivered to the US Institute of Medicine Forum on Microbial Threats found: “Every country engaged in World War I tried to control public perception [of the flu outbreak]. To avoid hurting morale, even in the nonlethal first wave the press in countries fighting in the war did not mention the outbreak”. But because Spain was not at war, its press reported the unfolding disaster, with the Spanish king being an early, much publicised victim. Spain was the first country in which political realities permitted the pandemic’s acknowledgement, rather than its origin.

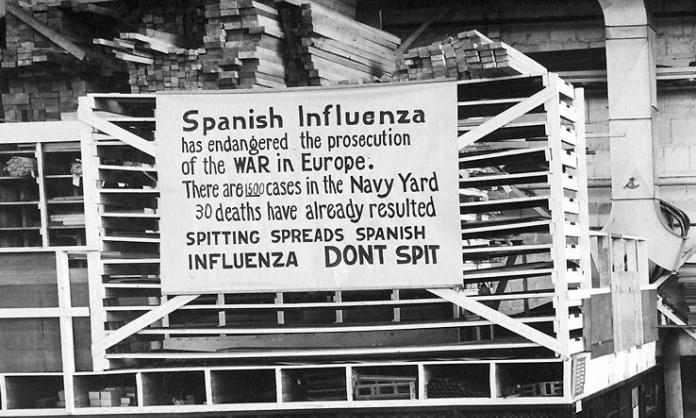

Much like today, most governments in 1918 tried to downplay the threat, pretending that their country wouldn’t be in danger. In the US, a law was passed that made it punishable by 20 years in jail to “utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the government of the United States”, including cursing or criticising the government, even if it was true. One congressman was jailed.

The architect of massive government propaganda proclaimed: “Truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms ... There is nothing in experience to tell us that one is always preferable to the other ... The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little if it is true or false”.

Does Trump hear echoes of this wisdom as he lies and says that everyone can have a test if they want, when there is a patent lack of clinics to do even the minimum? Or when he asserted that the virus would be under control in a few days when it was just beginning to spread?

The report’s authors conclude of 1918-19: “[A] combination of rigid control and disregard for truth had dangerous consequences. Focusing on the shortest term, local officials almost universally told half-truths or outright lies to avoid damaging morale and the war effort. They were assisted – not challenged – by the press, which although not censored in a technical sense cooperated fully with the government's propaganda machine”.

In Philadelphia, when the public health commissioner closed all schools, houses of worship, theatres and other public gathering places, one newspaper thundered that this order was “not a public health measure” and reiterated that “there is no cause for panic or alarm”. But these reassurances rang hollow as neighbours, friends and spouses died horrible deaths.

Dead bodies remained in homes for days, until eventually open trucks or horse-drawn carts were sent down city streets and relatives were told to bring out the dead. The bodies were stacked without coffins and buried in mass graves.

Between 50 and 100 million had died by the time the virus finally petered out in 1920, according to epidemiological studies. This was out of a world population of just over 1.8 billion. A similar mortality rate today would mean 175-350 million deaths. Epidemiologists claim it lowered life expectancy in the US by 12 years. In Australia, around 15,000 died in a population of 5 million.

These figures reduce to mere numbers what was unimaginable horror. A physician at one typical US army camp wrote:

“These men start with what appears to be an ordinary attack of LaGrippe or Influenza, and ... a few hours later you can begin to see the Cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the colored men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes ... It is horrible ... to see these poor devils dropping like flies ... We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day ... We have lost an outrageous number of Nurses and Drs. It takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce ... It beats any sight they ever had in France after a battle.”

With no effective drugs to treat the virus, scientists concluded:

“Some nonmedical interventions did succeed. Total isolation, cutting a community off from the outside world, did work if done early enough. Gunnison, Colorado, a town that was a rail center and was large enough to have a college, succeeded in isolating itself. So did Fairbanks, Alaska. American Samoa escaped without a single case, while a few miles away in Western Samoa, 22 percent of the entire population died.

“More interestingly – and perhaps importantly – an Army study found that isolating both individual victims and entire commands that contained infected soldiers ‘failed when and where [these measures] were carelessly applied,’ but ‘did some good ... when and where they were rigidly carried out.’”

The first cargo vessel carrying infected seamen arrived in Australian waters in October 1918, prompting the government to impose a seven days quarantine on ships from South African or New Zealand ports. Over the next three months in the Sydney quarantine stations, 300 cases were treated, with “numerous” deaths.

The unfolding tragedy was met with dishonesty and incompetence. The director of quarantine claimed to be convinced that by June 1919 they had created a situation of “absolute immunity”. The left wing historian Humphrey McQueen, who studied the pandemic in Australia, comments, “Dr J. H. L. Cumpston based this view on the fact that four weeks elapsed ‘between the arrival of the last infected ship and the first shore case notified.’ This would be strong evidence indeed if he did not elsewhere have cause to complain of medical officers on troop ships falsifying their records to avoid protracted quarantine.”

Some states closed their borders quickly, others later, leading to squabbling about who was responsible for new outbreaks and what could traverse borders. Shipping companies, in league with various governments, tried to subvert quarantine rules, resulting in acrimonious disputes about who was entitled to which trade. None of this conflict even considered what was best for the sailors and the population at large.

A big difference with Australia today was the restless spirit among returned soldiers who had looked into the gates of hell, urged on with promises of a golden future after the war. And workers had unions that actually saw their reason for existence as improving the lot of their members.

Industrial militancy had been strong since a general strike in 1917. Feelings among militant workers intensified in response to the contradictions between government measures intended to contain the spread of the flu, such as a ban on large gatherings, and employers’ demands to work in appalling conditions. In spite of government orders that only 20 people should be in a room together, for instance, the owners of the ship Loongana insisted on 24 sleeping in what a Board of Health inspector described as “dog kennel accommodation”.

Strong, militant unions did not accept any of this without vigorous resistance. The waterside workers and seamen were in the forefront of danger, with ships arriving carrying potentially infectious people. And they were also in the forefront of militant class consciousness.

In January 1919 seamen on the Arawatta moored in Moreton Bay walked off and refused to sign on again until they got conditions won by New Zealand crews. This included a 35 shillings a month wage increase, insurance of 500 pounds for families of workers killed by the flu, and full pay if they were quarantined or in hospital. Seamen refused to continue on the Cooma from Brisbane without these claims being met, in what was a wildcat strike. Shipping companies responded by leaving at least four ships in Queensland lying idle.

Transport workers in Sydney met and put all the same demands to employers. Waterside workers followed suit, also demanding cleaner facilities for meal breaks and washing and an extension of insurance protection to nurses, ambulance bearers and other occupations more likely to be at risk.

For the sake of business, some employers granted many of the claims, but the government would only guarantee wages of those in quarantine or hospital.

The 1919 Fremantle Wharf riot, also known as “bloody Sunday” or the “Battle of the Barricades”, was sparked by anger at ship owners’ reckless disregard for the health of waterside workers, inflamed by wider bitterness about low wages, casualised work and terrible conditions. A memorial fountain, sculpted by Pietro Porcelli in Perth’s Kings Square, pays tribute to Tom Edwards, killed by a cop during the riot. In the book Radical Perth, Militant Fremantle, Bobbie Oliver describes the events:

“On 4 May 1919, over a thousand wharf labourers (or lumpers as they were known), their wives and children had mobbed the wharf, thrown bricks at the Premier, faced armed police and seen one of their own killed and others injured ...

“For several days after the event, police officers feared for their safety on the streets of Fremantle. The funeral of Tom Edwards ... brought not only Fremantle but also the whole state to a standstill.”

The Dimboola had sailed into Fremantle in April carrying infected passengers. The state government, pressured by the prime minister to subvert their own quarantine period, organised scabs to unload it. They built the barricades that gave the event its name, to protect themselves. The Freemantle Lumpers Union, bearing the paradoxical acronym FLU, mobilised on the fateful day to stop scabs brought in boats down the river.

In May 1919 the Seamen’s Union went on the attack after confrontations and strikes in Queensland over wages, attempts to enforce quarantine of ships and the demands other ports had raised. Conflicts in a number of ports culminated in a four-month-long maritime strike. The seamen’s journal in Queensland suggested employing the “steel-fisted irony of the wobblies”, in McQueen’s words. If seamen got flu in any number, “they must immediately stroll up to the owner’s office and sneeze violently altogether at once. The owner will then immediately ... personally conduct you to his private hospital, calling at hotels en route, where you will receive every attention”.

With no vaccine and a health system even more woefully inadequate than today, the confused and outright despicable responses of governments and employers, determined to defend profits above all else, resulted in appalling misery for the mass of workers. Governments and employers determinedly resisted workers’ demands to be treated with some dignity.

Ideologically they attempted to combat the anger and radicalism by linking the crisis to the scourge of Bolshevism, see it as an opportunity to discredit the Russian Revolution, which had inspired millions to believe in the possibility of a better world.

One pamphleteer observed that the historical synchronisation between “epidemics of disease and epidemics of crime and social disorders” was being repeated as “the mysterious physical poison of influenza” emerged simultaneously with “a vast deluge of moral and mental poison, under the name of Bolshevism”.

Workers could not win everything, but they made substantial gains in pay and support for those unable to work. Critically, their struggles ensured the continuance of a militant minority determined to fight for workers’ rights and against the scourge of capitalism. This is an important lesson for today.