I was born long ago in 1894,

I’ve seen many a crisis I will own,

I’ve been hungry, I’ve been cold,

and now I’m growing old,

But the worst I’ve seen is 1934.

Oh, those beans, bacon and gravy,

they nearly drive me crazy,

I eat them till I see them in my dreams,

in my dreams.

But I wake up in the morning,

another day is dawning,

And I know I’ll have another plate of beans!

– “Beans, bacon and gravy”, a popular song during the Great Depression in Australia

The economic aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to be significant. Some economists are predicting a crisis on the scale of the Great Depression of the 1930s. The impact of the Great Depression in Australia was devastating. Families were scarred by it for generations. My grandfather grew up in rural Western Australia during the period and the privations he experienced stayed with him for life, leaving him with habits he kept till the day he died. He always, for instance, ordered more food than he needed. “You never know when you won’t have enough”, he once said to me.

The broader story of the Depression was one of millions of destitute, hungry workers tramping across the country begging for scraps and looking for work. It was one of families living in tent cities, queues for food and the rise of fascism. The lesser told stories are those of resistance – the struggles of the unemployed, workers and the poor. The tales of those who organised, agitated and campaigned should be remembered because they can give us hope that even in the most desperate circumstances we can resist.

Struggle didn’t occur automatically, nor did it track clearly upwards. There were ebbs and flows – sharp increases in industrial struggle followed by bitter defeats, periods of political radicalisation and periods of passivity and despair. There is no template for how struggle will develop during a period of crisis. Nevertheless, there can be value in looking at the development and shape of historical struggles, in order to be attuned to the possibilities of the coming period.

The economic collapse of the 1930s hit Australia as dramatically as it did the rest of the world. In fact, Australia, with its dependence on exports – particularly primary products such as wool and wheat – was among the hardest-hit Western countries. Unemployment reached an official record high of 29 percent in 1932 and GDP declined by 10 percent between 1929 and 1931. And according to many historians, these official figures underestimate the severity of the crisis.

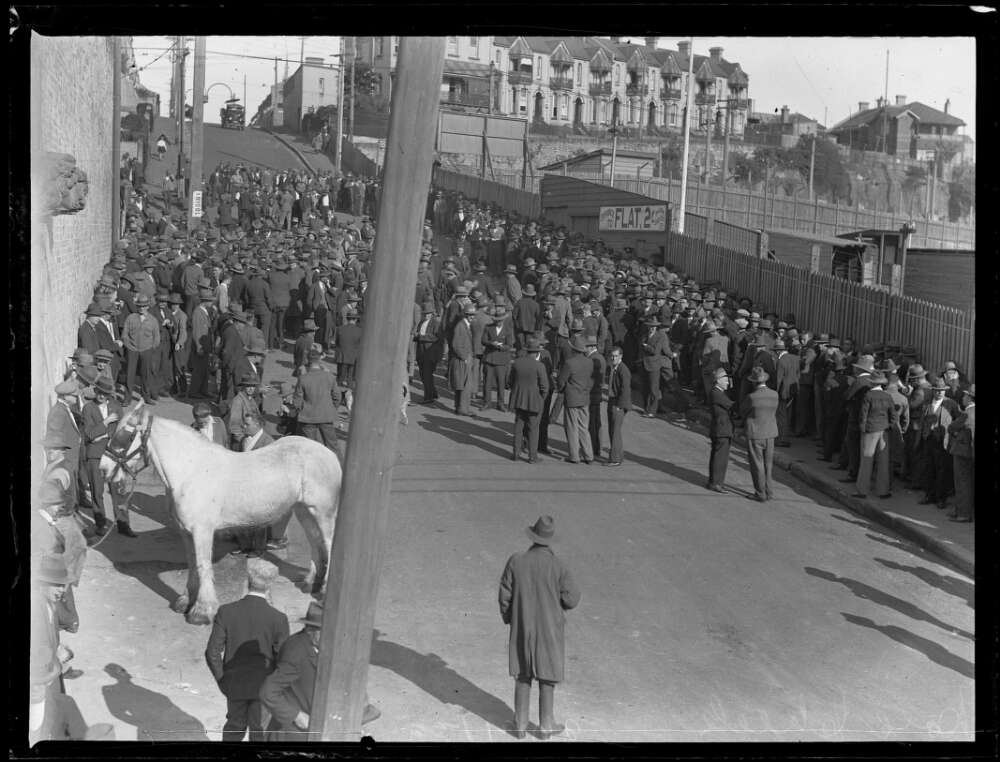

By the time of the Wall Street crash in October 1929, the opening shots in the class war had already been fired. Jittery and anxious about the future, the employers launched three major offensives – on the waterfront, in the mines and in the timber industry. The bosses hoped that smashing the unions in these key industries would leave them well placed to make workers pay for the crisis as the economy continued to tank. They sacked militants, banned unions and locked out thousands of workers. Workers resisted fiercely. Many of their stories were captured by Wendy Loewenstein in her 1978 oral history of the period, Weevils in the flour.

The miners in particular were bold and organised, and the state was determined to repress them. Their battle reached fever pitch at a demonstration in Rothbury, New South Wales, in 1929. One miner, Jim Comerford told of how the police attacked the workers:

“The pandemonium is difficult to describe. Men who’d been battened were screaming, there were men fighting. I saw one fight: the policeman with his cap knocked off, his uniform ripped all over the place. He and a young man were fighting on the buffer boards between the wagons ... I saw an old man forced onto his knees by a policeman, his cap was knocked off, blood was streaming down his face. He was obviously unconscious and the policeman was holding him up. His face was a fury, a mass of sheer bloody passionate hatred, working on this old bloke with a baton. A couple of young blokes went up behind him with a huge waddy and hit him on the back of the neck. They knocked him out of action and dragged the old bloke out.”

Lives were marked by these kinds of battles for years afterward. One radical timber worker described how in Erica, a small Victorian timber town, for years, workers remembered who had scabbed and who hadn’t:

“There was only one little hotel and a wine shop in the town. Pay day was once a fortnight. You’d walk in from the mill, maybe ten miles from the town, you’d settle your bills and go and have a beer before you walked back. Well after the strike was finished, people who had worked couldn’t drink at the hotel on pay day, they had to go to the wine shop. They weren’t allowed in the bar while there was a unionist in the place.”

In the end, the employers emerged victorious from these early battles and many militants were sacked and some were prosecuted. Union organisation was battered by the experience and a general sense of demoralisation among the workers was reinforced by the cowardice, passivity and conservatism of the union leadership. While some union leaders made vague statements about the need to challenge worsening conditions, more often than not it was rhetoric devoid of any commitment to action. In 1930, engineering fitters at the State Electricity Commission in Yallourn were the only significant group of Victorian workers who took industrial action to defend their rights. Union leadership after union leadership caved – even in the face of one of the most severe arbitration rulings of the period, a judgement which cut the basic wage by 10 percent.

The industrial confidence of workers was in free fall by the middle of 1930, but simultaneously there was a political radicalisation. A minority, particularly in the coalfields of northern New South Wales, drew radical conclusions from the defeats. Many began to distrust every institution of capitalism. Mine worker Jim Comerford again made the point to Loewenstein: “All these men who’d been heroes in the war, they didn’t mean a thing. They’d been extolled as the heroes of this earth, then they’d suddenly become the industrial scum. The law and the order, justice, everything that was preached into us didn’t mean a thing. They were victims of everything they’d fought for”.

Many workers felt the union leaders were too timid and that the battle had not been waged hard enough. The radicalisation of this minority enabled the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) to begin to build a modest industrial base.

The unemployed began to draw radical conclusions from the worsening economic situation. Being unemployed in Australia in the 1930s was tough. The dole was meagre or non-existent and many state governments and local councils launched a series of punitive campaigns to make relief harder to come by. Tens of thousands of people couldn’t pay rent or afford necessities. Homeless encampments sprung up on city fringes. Thousands of unemployed, mainly men, became tramps – walking up and down the length of the country seeking work. The existing capitalist institutions were either incapable of or disinterested in helping the unemployed. The desperate situation prompted tens of thousands to join the militant and defiant Unemployed Workers Movement (UWM).

The UWM led a variety of campaigns. They also launched a series of high-profile anti-eviction struggles. When word got around that a family was going to be evicted for not paying rent, the UWM would put out the word and dozens of unemployed activists would arrive, put up barricades around the house, blockade the front door and refuse to allow the family and their furniture to be removed. Jocka Burns of Yarraville in Melbourne described the method:

“When an eviction case was coming up, we’d ask the people what they were prepared to do. You’d say to the husband ‘Listen, we can get some accommodation for your wife and kiddies, providing that you’re prepared to fight the eviction’. The women played an important role here, put up bunks for the kids. The bailiffs would put the furniture out. We’d put it back in. We’d have four, five, six-hour shifts.”

On occasion this was met with police violence. In June 1931, for example, the Sydney Morning Herald described how one of the “most sensational battles Sydney has ever known was fought between 40 policemen and 18 Communists” in Newtown to stop an eviction:

“Entrenched behind barbed wire and sandbags, the defenders rained stones weighing several pounds ... on to the heads of the attacking police, who were attempting to execute an eviction order. A crowd hostile to the police, numbering many thousands ... threatened to become out of hand ... When constables emerged from the back of the building with their faces covered in blood, the crowd hooted and shouted insulting remarks.”

The UWM also organised alternative relief distribution, strikes of workers on “work for the dole”-type schemes, and street protests to improve the standards of sustenance. The movement experienced meteoric growth. In the first few months of 1931, the UWM grew to 60 branches in New South Wales. Importantly, the unemployed weren’t just recruited as activists. They were also, in many cases, recruited to a communist worldview, an outlook that stayed with many UWM members longer after the organisation disappeared. The CPA recruited a significant number of leading UWM members who went on to be leaders in the working-class movement for many years.

Another expression of the political polarisation that occurred in the Great Depression was the rise of New South Wales Labor premier Jack Lang. Lang, commonly known as “Big Fella”, had positioned himself in the early years of the Depression as the saviour of the Australian working class. He was one of the only Labor leaders arguing for a policy of defiance towards the banks, for restoring the 44-hour week, against salary cuts to public servants and for large investments in public works to reduce unemployment. Workers across the state had portraits of Lang hanging in their living rooms and plaster busts of him on their mantelpieces.

Lang was no revolutionary. In fact, he declared that “as a loyal subject and servant of the King, you will find me free from all traces of Bolshevism and Communism”. Before entering politics, he had been a real estate agent – a profession not often known for its revolutionary tendencies. Nevertheless, Lang came to represent, for a time, the great hope for millions of working-class people across New South Wales and the country.

In times of social and economic crisis, the ruling class and its institutions can be thrown into turmoil. In Australia, they were riven with disagreements about how to rescue capitalism from its parlous state. Lang’s reforming project, moderate as it was from a revolutionary standpoint, proved too much for many in the establishment. The middle classes were in apoplexy. Column after column in the daily newspapers was dedicated to the supposed civilisational threat that Lang posed. They worried that Lang’s defiance could act as a spark to light the flame of rebellion among the masses.

The All For Australia League set up a defence organisation to “combat the anarchy” it feared would occur if Lang implemented his proposals. This sort of organisation blossomed across the country. Eric Campbell of the fascist New Guard thought that the state government ought to be put in the hands of a commission and that parliament ought to close itself down. Graziers helped organise the secessionist New Staters and the Riverina Movement. These movements armed and drilled local farmers and organised rural townships in preparation for the moment Lang introduced his policies. When he did, they were going to fight to break up New South Wales into smaller states that they could control.

In October 1931, the state ALP executive was expelled from the federal ALP for refusing to go along with federal Labor’s austerity measures. There were now two Labor parties: the federal one around prime minister James Scullin and the New South Wales one around Lang. Such dramatic measures intensified the political polarisation.

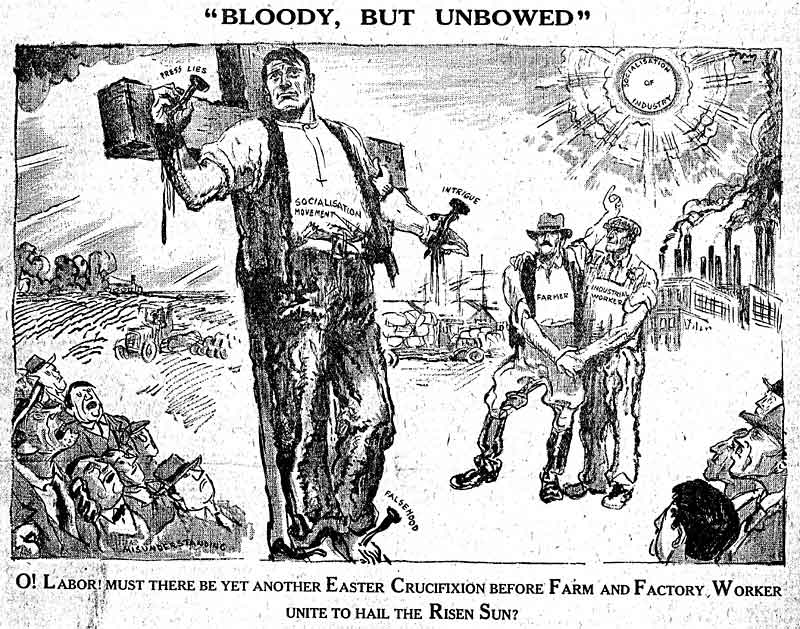

The working class responded with a similar political, though not industrial, intensity. The main expression of this was in the organisation and rapid growth of the “socialisation units”. These groups emerged within the ALP to “carry the message of a saner, better and more efficient social system through socialisation to those hundreds of thousands of misguided victims of capitalism”.

The socialists at the heart of this movement were convinced the ALP could be transformed into a socialist organisation that could, when in power, nationalise industry and put production in the hands of the workers. There were many debates about how exactly this process would occur. Some in the units argued that the ALP needed to lead the workers in a violent revolutionary struggle for political power, while others argued that workers needed a general strike to overthrow capitalism before socialism could be introduced by the ALP. Others suggested that an election with a mandate for immediate socialisation would be the way workers control would be established.

But while these debates raged, the thing most of those involved in the units agreed on was the need to convince workers of socialism through a massive educational effort involving regular public meetings, distribution of leaflets and fundraising.

The units became incredibly popular, drawing in mainly young workers. By 1931, there were 97 units mobilising thousands of people. At its height, 178 of the 250 Labor Party branches around Sydney had active units, some bigger than the branches themselves. They published a paper, Socialisation Call, which had a wide readership across the country. In 1932, there were five central Sydney educational classes, plus 25 suburban classes, covering subjects like history and economics. The movement even had an orchestra and a theatre group. Thousands of workers were coming to think of themselves as socialists.

Nevertheless, the socialisation units were not welcomed by Lang and his entourage (known colloquially as the “Inner Group”). While occasionally genuflecting to socialism, Lang viewed the growing success of the socialisation units as both a factional and a political threat. Increasing the confidence of radicalising workers was a dangerous game. As a left populist with no interest in overthrowing the system, Lang didn’t want to see the development of a revolutionary current. Behind the scenes, he did everything he could to undermine the units.

There were also several fault lines in the politics of the leadership of the units. Most fundamentally, they were unclear about how to get from capitalism to socialism. That they were committed to the ALP as the vehicle for change was indicative of this lack of clarity. For a period, however, the units were the focal point for a rapid and deep radicalisation among key sections of workers. There would, no doubt, have been huge opportunities for the revolutionary left to push things forward and to grow out of these milieus. Unfortunately, the sectarianism of the CPA got in the way.

The early 1930s was the height of the so-called Third Period. The CPA, like other communist parties around the world, was taking its line from the Stalinist USSR. The Third Period line said that the world was on the brink of revolutionary upheaval and all communist parties needed to act as disruptive agents and make no compromises with more conservative, social democratic layers. In Australia, this meant bitter hostility to the ALP. This perhaps would have been fine if it had have meant finding ways of relating to radicalising workers inside the socialisation units and winning them away from social democracy. Unfortunately, it was interpreted by the CPA leadership to mean complete abstention and sectarian hostility not only to the ALP leadership or union bureaucracy, but to anyone, rank and file workers included, who in any way identified with them.

Scullin lost government in 1931 and the United Australia party leader Joseph Lyons moved to attack Lang. Using Commonwealth financial powers, Lyons began to appropriate state government revenues to reimburse the federal government for interest payments made on behalf of New South Wales when Lang had refused to pay earlier. For a time, Lang defied the Commonwealth by withdrawing public money from the banks and even barricading the Treasury against Commonwealth officers. State and federal police were locked in physical battle with each other, such was the crisis.

At this point, on 13 May 1932, the governor, Philip Game, dismissed Lang. Workers were furious and there was a huge mobilisation on the streets. A near revolutionary mood infused the air. The Labor Council made plans for a “paramilitary mobilisation of unionists”, prompting an excitable New York Times correspondent to report the emergence of a “Red Army”. In the subsequent election campaign, Lang spoke to crowds of a quarter of a million workers.

Nevertheless, the potential of this situation was squandered by the continuing sectarianism of the CPA, the confusion of the leaders of the socialisation units and the fact that the Inner Group around Lang – afraid of the growing revolutionary fervour – moved to close down the units and dampen the anger of the workers.

In 1933, there was something of a recovery in the world economy, which, in time, flowed through to Australia. This in turn saw the return of industrial confidence among workers. Not only did workers fee they had more bargaining power; many of the unemployed who had been radicalised through their experience in the UWM were now coming back into the workplaces as hardened militants. In some workplaces, the mines in particular, union activists who had been the first to lose their jobs were also finally getting work.

Over time, there was an increasing level of politicisation and industrial militancy. One example is the Miners’ Federation. Two communists were elected to the leadership of the union, which increasingly took on a more industrially and politically militant tone. The Militant Minority Movement (MMM), an organisation established by the CPA to cohere the most determined and fighting unionists also began to grow. This didn’t happen automatically. The success of the MMM reflected the steady work of a core of politically committed communist militants over the preceding four or five years. They plugged away – raising issues such as increasing mechanisation and combining union arguments with broader political messages about capitalism and workers’ rights.

International developments also began pressing themselves on the consciousness of Australian workers. Hitler had come to power in Germany in 1933. Italy’s fascist dictator Mussolini was on the march. The questions of fascism and war were increasing in urgency. The left on university campuses began to grow – there were increasing numbers of public protests and meetings against the prospect of war and fascism. All of this began to impact on workers too. In 1934, for instance, the central council of the Miners’ Federation developed the following motion regarding the possibility of war: “In proposing these steps in the mobilising of the working class forces on a national and international scale against imperialist war, this Council also declares that a final and lasting peace can only be secured by the overthrow of capitalism, which is the cause of imperialist war, and the institution of socialism”.

The pickup in the economy did not mean, however, that the bosses were prepared to let up on the working class. The Victorian Railways Department, headed by Robert Menzies – which had control over the Victorian mines at the time – pushed management to sack a group of miners in Wonthaggi. A tremendous five-month strike followed in 1934. The CPA-aligned MMM gained leadership of the strike, reflecting a growing hostility to the bankrupt conservatism of the old union officials. The threat of a nationwide strike by miners eventually forced Menzies to back down.

This victory spurred on other. Over the second half of the 1930s, leading to the outbreak of World War Two, a new spirit of industrial militancy took hold. This mood continued, in fact, into the early years of the war. With the beginning of the war in the Pacific in 1941, there was a lull. But the working class had just hit the pause button – the lessons of the Depression weren’t forgotten. Many of the leaders of the rank and file waited out the war and then, in the late 1940s, played their part in one of the biggest industrial upsurges in Australian history.

Karl Marx said of capitalism, “all that is solid melts into air”. This line captures with poetic insight one of the most fundamental lessons of the Great Depression and indeed, of today. All the certainties, all the dreams, all the plans, all the hopes we had, can disappear as quickly as fog in sudden sunlight. Capitalism destroys futures. It is a system of endemic crisis and it always was and always will be workers and the poor who are forced to pay.

The best response from our side is to fight. We have to. If we don’t, capitalism will grind us into dust. The workers and unemployed and students who threw themselves into the battles for human dignity during the 1930s demonstrated that we can resist. The successes of those struggles depended on the political shape of them. We can’t know how the situation will develop now. But we do know we have the fight of a lifetime on our hands.