“In terms of media coverage, you have to run within the Democratic Party”: that was how Bernie Sanders pragmatically justified his participation in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries, an approach that DNC apparatchik Donna Brazile called an “extreme disgrace”. In February of this year, as he campaigned against neoliberal candidates like Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg, a fundraising email to his supporters proclaimed: “The choice in this election is simple: democracy or oligarchy. Will billionaires once again buy the presidency? Or will working people finally stand up, fight back, and take it back for ourselves?”

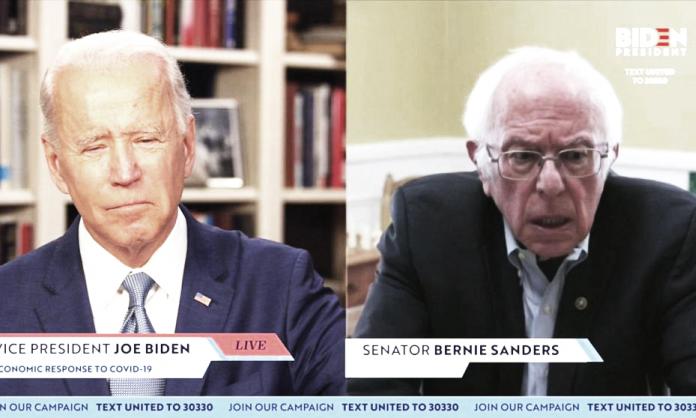

A couple of months later, Sanders was telling Joe Biden – a man who suggested he would veto Sanders’ signature Medicare-for-all policy – “We need you in the White House ... I will do all that I can to see that that happens, Joe”. By the terms set in his own campaign, Sanders is now enthusiastically advocating and campaigning for a representative of oligarchy against democracy.

Bernie Sanders’ campaign always rested on a contradiction. It appealed to the left-wing sense that the Democrats – particularly as embodied in Hillary Clinton – were as much part of the problem as the Republicans. At the same time, Sanders really tried to win the Democrats’ nomination for the presidency: that rested on, and reinforced, the belief that it’s impossible to achieve change outside the USA’s two-party framework, which seeks to limit political action to the boundaries of two right-wing capitalist parties.

Now Sanders has been comprehensively defeated, his supporters will have to move on to a new fighting stance, if they aren’t to sink back into apathy or the political mainstream. Sanders’ campaigns could reflect an early stage in the development of something really important: a struggle against the US capitalist class that takes place beyond elections and outside the boundaries of the Democrats. It’s understandable that so many people hoped to take on the powerful without breaking the rules of US politics, and it’s understandable that they tried that path seriously. Now that path has been shown to be blocked. The only hope is that those Sanders supporters move on to more effective paths – independent political organisation and struggle beyond the electoral sphere.

Now’s a good time to take stock of the strategic approaches taken up on the left – who were, in many cases, so allured by the promises of an easy path to power and focussed so intensively on the presidential election that they are now arguing against any attempt to escape the boundaries of Democratic electoral politics.

You can see a model of this trajectory in the writings of Dustin Guastella, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America and a frequent contributor to Jacobin magazine. In 2016, against those who warned that the Sanders campaign could lead supporters on a path to doomed efforts to reform the Democrats, Guastella insisted: “We do not see Sanders as a realignment strategy for the Democratic Party”. After Sanders won the 2020 caucus in Nevada, Guastella announced that the realignment was in fact complete: “Face it, establishment Democrats – it’s his party now”.

After Sanders’ second campaign was defeated, the internet exploded with an enormously positive phenomenon: declarations from rank-and-file Sanders supporters that they’d never vote for Biden and they were finished with the Democrats. At that point, Guastella launched a bitter polemic against anyone who might think about leaving the Democratic Party, while rationalising Sanders’ incorporation into its core. “We have to run congressional candidates”, Guastella declared, “to start to build a real bloc of lawmakers ... [This] requires rejecting the fantasy that now is the time we all throw ourselves into third-party work or militant protest activity”. In a separate article, he explained: “Voters are more clever than third-party advocates, and they would rather not hitch their wagons to a candidate who has no chance of winning ... Any talk of their ‘DemExit’ resulting in a consequential ‘break’ with the Democratic Party is simply fantasy”.

“We know Bernie Sanders has no interest in third-party fantasies”, Guastella noted approvingly. Instead, Guastella recommended Sanders link up with union officials to launch an “ongoing nationwide pressure campaign” for good policies – hardly the radical break with establishment politics we were promised.

This pretty much sums up the trajectory of the current associated with Jacobin and the “Bread and Roses” faction in the Democratic Socialists of America, to which that publication is linked. In 2016, it was denial: denial that they had any interest in long-term habitation in Democratic Party electoral politics. From 2018 to 2019, it was delusion. This phase was characterised by hallucinatory claims that Sanders’ presidential campaign was in fact a quasi-revolutionary movement that threatened to dissolve the structures of capitalism itself. Now, in 2020: defence of the Democrats.

Bhaskar Sunkara’s 2019 Socialist Manifesto suggested that, because Sanders was a “class struggle” candidate, his 2020 victory could be the signal for a relatively swift revolutionary transformation of US capitalism. After Sanders’ defeat, Connor Kilpatrick gave this truly depressing call to stick with the program: “I’d say we’re looking at no more than twenty or thirty years max for a decent social-democratic project to truly take hold of American life”. And that’s the best we can hope for. Challenging capitalism? Forget it.

This political current boasted that they were the ones who saw the most revolutionary potential in Sanders. Why are they now trying to drain all radical hope from the socialist movement, in the midst of capitalism’s greatest crisis in decades? How can you start by claiming that Sanders’ campaign was good precisely because it had a supposedly unique power to inspire strikes, generate a split from the Democrats and initiate the socialist transformation of America – and end by denouncing any attempt to split from the Democrats in order to focus on independent class struggle?

“Parties are not ends in themselves”, Guastella writes, “but means to help us do two things: 1) elect candidates, and 2) enact legislation”. In the end, no matter how many times one might invoke the 99 percent against the oligarchy, this is a thoroughly elitist approach to social change: it sees political organisations existing only to support a small layer of professional politicians. Real change is made by elected candidates and legislators: collective political life, embodied in parties, allows ordinary people to take part at a passive supporting level only, campaigning on behalf of the people who really matter. In this world view, even collective actions, like demonstrations and strikes, are helpful only to the extent that they build electoral majorities.

This approach has poisoned the socialist movement for over a century. By subordinating socialist politics to the structures of bourgeois politics, it has turned anti-capitalist organisations and movements into administrators of the capitalist state. This process never ends: each generation that struggles for equality is lured by it, as capitalist electoral politics offers itself as the only apparently realistic way to change the world – and so captures movement after movement. The only alternative is to base socialist politics on Marx’s theory that the working class, through revolutionary action, can build their own structures to reorganise society from below.

Writing on the prospects for Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, Richard Seymour warned of the likelihood of “‘syrizafication’, a process wherein the radical Left is swiftly chewed up and metabolised by the institutions it seeks to govern, becoming in effect an instrument of the neoliberal centre that it was elected to displace”. The reference is to Syriza, the new Greek political party that was elected to government on a platform of fighting austerity, only to implement the harshest cuts that country had yet seen. But Syriza made it further than Sanders: not only did Sanders never form government, he never formed a new party – or even tried to.

US apologists for working within the Democrats often point to the unique constraints of their country’s two-party electoral system. It’s true that the domination of two capitalist parties does impose even heavier burdens on the US left. That means that the task of breaking with the Democrats is more urgent, and requires more political courage. If you believe that parties exist only to elect candidates and enact legislation, escaping from the Democrats is much harder: no third party is likely to win loads of races and enact legislation in the US. For leftists, first you have to believe that parties, and political organisations, can serve other purposes – organising the oppressed to fight against their oppressors, raising people’s consciousness to inspire them to fight, disrupting rather than just dominating the official power structures.

In the context of an electoral battle between two senile right-wingers like Biden and Trump, votes for a third party can be an important signal that people want an alternative. If you think political parties exist to inspire the oppressed to fight for their own rights, signals like that can matter. If you think that parties exist to pass legislation, such signals are irrelevant.

The same applies to independent class struggle and mass mobilisation: it has to be seen as an end in itself, not just a prop for electoral candidates, if it isn’t to evaporate into nothing once your candidate loses the nomination. An electoral obsession, combined with the terrible political landscape in the United States, has led Jacobin’s strategists of the Sanders campaign to argue against any open challenge to one of the oldest and most reactionary parties in world capitalism.

Some of Sanders’ supporters have a much better understanding of what’s at stake than the strategists at Jacobin – hence the popularity of the #DemExit hashtag that Jacobin had to campaign against. (Since Sanders’ defeat, the hosts of the Chapo Trap House podcast have mused about the irrelevance of voting, the importance of class struggle at the point of production, and the absurdity of long-term attachment to the Democrats based on the illusory idea that Sanders “won the battle of ideas”.) A socialist current that could argue the need for independent anti-capitalist organisation with courage and clarity would no doubt find an audience, though that audience might take a lot of patient convincing. Sanders won’t be the last candidate to gain a mass following based on an inspiring but flawed vision of socialism. Socialists have a duty to help their supporters come to understand that they themselves have the power to end capitalism, rather than rationalise staying within the boundaries of the structures of official capitalist politics.