Sub-Saharan Africa is facing its greatest crisis in generations. The continent thus far has been less affected by the pandemic than other parts of the world. But the impact of the global economic crisis is already enormous.

The first transmission points were financial markets, which tailed Wall Street’s dramatic March declines as investors ran for the doors. Unlike in some of the more stable developed economies, however, where investors headed for government-backed securities, money wasn’t simply transferred from the private sector into government debt. It fled the continent for the safety of US treasuries. Local currency collapses against the greenback squeezed debtor countries everywhere. That was followed by surging borrowing rates.

“Concerned and trembling in our boots about what might be in the coming weeks and months” was how South Africa’s finance minister described the outlook after credit ratings agency Moody’s cut the country’s debt rating to junk status in late March. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have now stepped in to prevent sovereign debt crises tearing through already fragile global markets.

Just as debt markets have been strangled, domestic incomes are contracting, and with them investment and consumption. Commodity exporters on the continent face depressed sales and volatile markets. Oil, which accounts for 40 percent of Africa’s exports, reached giveaway prices in late April. Angola, Cameroon and Nigeria, among others, are being hard hit. Coffee prices are at 10-year lows, hitting producers in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda.

The tourism industry, worth tens of billions of dollars a year in income, has ground to a halt in eastern and southern Africa. “The cessation of air travel has had an unprecedented negative effect. Most, if not all, tourist hotels have closed and the workers have been sent home, many without any income for survival”, Communist Party of Kenya secretary general Benedict Wachira says via email from Nairobi, the capital. “Those in the tourism related transport sector, the artisans who depend on tourists and the whole chain of workers therein are facing a very grim future.”

The World Bank is warning of an agricultural production crisis as supply chains seize and global trade slows. And the currency collapses portend devastating food price rises in importing nations. World Food Programme executive director David Beasley says that an emerging “hunger pandemic” could result in 300,000 deaths per day globally. The aid organisation estimates that the number of people suffering acute hunger could increase from 135 million to 265 million by the end of the year, with sub-Saharan Africa being one of the worst hit areas.

Remittances – money sent home by migrant workers living abroad – are usually the first form of financial help when private capital flees, and they have become more important in the last two decades, overtaking foreign direct investment, private capital and aid as the largest inflow of wealth to poorer countries. But with economies all over the world shuttered, those lifelines are being severed.

Adding to the external shocks, many African countries have imposed their own lockdowns to prevent the pandemic getting out of hand. Almost all countries now face a perfect storm of economic devastation. According to the International Labour Organization, more than 85 percent of employment across the continent is informal – untaxed, unregulated, unprotected. Most workers lack a social safety net. “The emerging human costs include job losses, reduction of salaries, closure of small/informal businesses affected by social distancing guidelines and curfew and homelessness caused by landlords evicting tenants who cannot afford to pay rent”, Wachira says.

In Ethiopia, the poverty rate halved in the last decade and incomes almost doubled. “We anticipated a 10 percent increase in exports and a 32 percent increase in remittances, all supporting a 40 percent increase in our reserves”, prime minister Abiy Ahmed wrote in a 12 April Bloomberg piece. Now, he says, those targets are “in tatters”.

--------------------

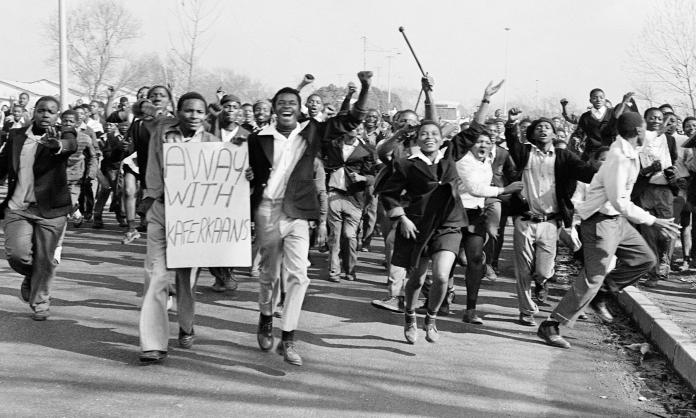

Economies and livelihoods aren’t the only things being torn up. Ethiopia has declared its third state of emergency in four years. And it has banned the dissemination of information critical of the government directive, while handing powers to the military to crack down on political parties, the media and demonstrations. In Togo, the government declared a similar emergency, deploying 5,000 troops, who reportedly beat civilians. In fact, reports from all over the continent suggest that many governments are using the pandemic to enact sweeping powers, which primarily are being used against the poor.

South Africa, which has imposed one of the most stringent lockdowns in the world, is an example. “In the Alexandra township of Johannesburg, residents gathered outside a school on Easter Saturday to receive parcels of food. Two days later they had not received anything. Whilst walking back to their shacks they stopped in groups to discuss the dire situation that they were in. Police then pounced on the groups and opened fire with rubber bullets”, Socialist Revolutionary Workers Party member Ashley Fataar says via email.

“In the Mitchells Plain township of Cape Town, a group of residents turned up for food parcels. When the parcels did not arrive, the residents refused to leave the streets and fought with police. Other areas of Cape Town saw youths looting food shops. A provincial governor admitted that 20 percent of the population of the province is normally food insecure. During the lockdown, that figure had doubled. Thousands of workers tried to leave for their rural homes. They were stopped and ordered back to where they had travelled from. In all cases where workers have protested, the state’s response has been one of brutality. Up to 10 people have been killed so far and many others injured by being shot with rubber bullets or having soldiers smash rifle butts into them.”

In Nigeria, the most populous country on the continent, some argue that enforced social distancing is almost impossible and must be reconsidered. Up to 20 people have been reported killed in the crackdown. “We have gradually reached a consensus that government talk of lockdown is a lot of nonsense because they cannot really keep people at home”, Gbenga Komolafe from the Federation of Informal Workers’ Organizations of Nigeria writes in the Review of African Political Economy.

“It can’t be otherwise in a situation where seven people live in a room and 75 people share a toilet and bathroom and people are forced to literally live on the streets, and that’s not even the technically homeless ones. What we have had therefore is a mere ‘lock up’ of people’s livelihoods. In this scenario, only God knows how we can determine the thousands of people killed so far under this lockdown by hunger and hunger induced illnesses. The only logical demand would be to radically scale down this lockdown while urgent steps are taken to provide means for people to maintain basic health protocol for COVID-19 prevention.”

In Kenya, it’s a similar story. “The Police have, with tacit approval from the government, used social distancing directives to kill, maim, brutalise, detain and extort money from the populace, especially those from working class, poor and peasant backgrounds”, Wachira says. “On 22 April, the death toll from COVID-19 stood at 14 deaths, while the death toll from police ‘enforcement of COVID-19 directives’ stood at more than 25, not to mention the unreported cases and the terminal injuries inflicted. Even children have not been spared.

“The police are now arresting people, especially in low income areas, en masse, and demanding bribes. Failure to pay leads to either being kept in the cell, or being taken to the government ‘quarantine centres’, which are just detention facilities by another name. The curfew and the cessation of activities has been ongoing for five weeks now. However, given the extent of poverty in Kenya, and given the likelihood that the government is not capable of providing food to those in need, and adding the general effect on the economy, I do not see these directives lasting for another five weeks. The economy cannot sustain it, and the capitalist state would not want to risk and test how far the masses can go.”

--------------------

Economies are crumbling and political rights are being usurped, but the early and dire predictions of coronavirus health devastation in Africa have, thankfully, not yet been borne out. In the sub-Saharan region, which is home to more than 1 billion people, only South Africa has registered more than 2,000 cases. While a lack of testing is clearly resulting in under-reporting, hospitals have not been overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases in major cities – so it’s not just testing. There’s plenty of speculation about why this is the case, from the relative lack of older people on the continent (the median age is 18, compared to 42 in Europe, and only 3 percent are over 65) to climatic conditions hampering the spread of the virus.

Case numbers nevertheless are rising steadily, by up to 1,000 per day. Many countries in the rest of the world went through a period in which the outbreak seemed contained or manageable, only for it suddenly to overwhelm health systems. If the trajectory in any way begins to approximate that in Europe, there will be a big problem. Across the continent, some 200 million people live in slums. In more the 20 countries, fewer than one-quarter of households have basic hand washing facilities.

“For a virus whose elimination is based on proper hygiene and social distancing, the slums and the low-income areas of the cities only offer the opposite of these”, Wachira says. “People live in crammed shanties with no tap water and limited sanitation facilities. Many of these people live from hand to mouth – it is difficult to imagine the possibilities of a full lockdown like the ones that we are seeing in South Africa and in the developed countries.” In short, “flattening the curve” will be next to impossible if the pandemic breaks. Health systems inadequate in regular times will not be able to trace, isolate and quarantine people, let alone treat acute cases – many countries count ventilators and intensive care beds in the dozens, rather than the thousands.

Yet, even if for some reason the region emerges relatively unscathed from the health crisis, lasting damage is being inflicted by other means. It is clear already that this is a generational crisis.