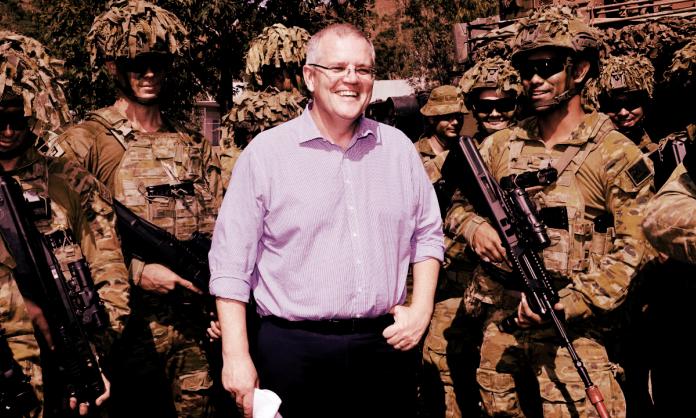

The Australian government and its big business backers are preparing the ground for an aggressive expansion of the fossil fuel industry and a further weakening of environmental protections when the country emerges from the COVID-19 crisis. At a time when many are calling for a rethink of the “business as usual” of capitalism prior to the pandemic, prime minister Scott Morrison and his Coalition colleagues have made clear their intention to double down on the most destructive aspects of the system to revive corporate profits.

The centrepiece of the government’s vision is the further rapid expansion of Australia’s gas industry – a major driver of climate change. “Gas already plays an essential role in energy reliability, but it could be even more important through a gas-fired recovery”, energy minister Angus Taylor told the Sydney Morning Herald. “We want to have demand for affordable gas matched with priority upstream investment opportunities to bring gas where it is needed and provide economic stimulus.”

Resources minister Keith Pitt has shown similar enthusiasm for a gas-fired recovery. In a 17 April media release, welcoming an announcement from Arrow Energy that it will expand its coal seam gas operations in Queensland, Pitt said that energy and resources will be front and centre for economic growth. “Notwithstanding COVID-19”, he said, “our energy and resources will be important in getting not just our economy back on its feet, but vital in assisting our important trading partners to kickstart their economies”.

The idea of using the crisis to accelerate fossil fuel development appears to have occurred to the government in the earliest days of the pandemic. One of Morrison’s first acts was to establish the National COVID-19 Coordination Commission. The membership of the commission tells you everything you need to know about the kind of advice the government expects it to provide. It is headed by mining magnate Neville Power. Power is the former CEO of Fortescue Metals and current board member of Strike Energy. Both companies are major players in the gas industry.

Also members of the commission are Catherine Tanna and Greg Combet. Tanna is the managing director of electricity and gas retailer EnergyAustralia. She has an illustrious career in the global oil and gas industry behind her, including executive roles at Shell and BHP Billiton. Combet is no better. His status as a former head of the Australian Council of Trade Unions and minister for climate change in the Rudd Labor government appears not to have given him any qualms about becoming a shill for the fossil fuel industry after he left parliament in 2013. He has since been a highly paid consultant for several major coal and gas companies, including Santos and AGL.

“I have always been a fossil fuels man”, declared Combet in 2014. In the same year, in an article for the Australian Financial Review, he pointed to the massive expansion of the shale gas industry in the US as an example for Australia to follow. “The inability of industry and governments at all levels to effectively address the community’s environmental concerns about coal seam gas, and political opposition to its development, are creating substantial economic risks in south-eastern Australia”, he said. Finally, there’s Andrew Liveris – former chair and CEO of the Dow Chemical Company, one of the world’s three biggest chemical manufacturers and a major producer of fertiliser.

Based on recent public statements by Power, you’d think he just sat everyone down and made a list of projects reflecting their immediate business and financial interests. As reported in the Daily Telegraph on 24 April, at the top of the commission’s list of projects is a $2 billion fertiliser plant at Narrabri, which would be powered by a proposed Santos coal seam gas project nearby.

The Santos project is yet to receive approval from New South Wales planning authorities and is opposed by many locals and farmers. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, however, it was being touted by premier Gladys Berejiklian as a way for the state to deliver on its promise to expand gas production in line with a $2 billion energy agreement signed with the federal government in January. Power’s intervention appears calculated to speed up the approvals for the project.

The Narrabri fertiliser and coal seam gas projects are just the start. In an earlier interview with Fairfax, Power pointed to the potential to open coal seam gas and fracking operations across Australia. “We have significant reserves of gas on the east coast that are not connected up”, he said. “We have significant reserves in central Australia and significant reserves in Western Australia.” According to the Guardian, the commission is also pushing a previously rejected plan to build a pipeline linking major gas projects off the coast of Western Australia with cities on the eastern seaboard.

Gas is often touted as an environmentally friendly alternative to coal. At the height of Australia’s summer bushfire crisis, energy minister Taylor argued in the Australian that “our LNG exports are dramatically reducing emissions in customer countries such as Japan, South Korea and China”. But while gas may produce fewer emissions than coal, it’s still among the biggest sources of global emissions. According to a 2019 report by Climate Analytics, Australian gas exports contribute 0.6 percent of total global emissions from burning fossil fuels. Today, with the further rapid growth of the industry, that figure would be even higher.

These figures don’t incorporate the likely high levels of “fugitive” methane emissions released during the mining and transportation of gas. Methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, about 84 times more effective at trapping heat over a period of 20 years. Scientists estimate that a leakage rate of just 3 percent from gas mining and transportation would be enough to wipe out any advantage it has over coal, in terms of emissions intensity. US studies have found that rates of leakage from shale and coal seam gas operations can be up to 17 percent.

In 2016, NSW Greens MP Jeremy Buckingham went to the Condamine River in Queensland and filmed himself on a boat igniting the water with a lighter. “This area has been drilled with thousands of CSG [coal seam gas] wells and fracked. This river for kilometres is bubbling with gas and now it’s on fire”, he said. If Power gets his way, this kind of thing will become a much more common sight for communities around Australia.

The current push for a gas-fired recovery from COVID-19 isn’t about tackling climate change, and it isn’t, as Power claims, about having “competitive energy prices”. Australia is already the world’s biggest gas exporter, shipping $49 billion worth of the stuff in 2019. The only reason Australian gas prices have been so high in recent years is because the major gas companies find they can make more money by selling the stuff on international, rather than domestic, markets.

The government’s plan is about one thing and one thing only: profit. Australia’s gas boom, along with the continuing expansion of the coal industry, has provided a profits bonanza. The kind of recovery the government has in mind is primarily a recovery in the fortunes of Australian big business, and it sees the supercharging of the fossil fuel economy as the fastest way to achieve this.

Many have suggested that the current crisis presents an opportunity to accelerate Australia’s, and the world’s, shift away from fossil fuels. The International Renewable Energy Agency’s (IRENA) Global Renewables Outlook, released in April, points to the potentially massive boost to economies that would come from significantly increasing government support for renewable energy. IRENA’s director-general Francesco La Camera commented, “By accelerating renewables and making the energy transition an integral part of the wider recovery, governments can achieve multiple economic and social objectives in the pursuit of a resilient future that leaves nobody behind”.

No doubt this is true. But to the extent that such arguments are made in the hope that governments might actually listen, they are hopelessly naive. If there’s one thing the neoliberal era has shown, it’s that governments like Australia’s aren’t concerned with building “a resilient future that leaves nobody behind”. Part of the purpose of neoliberalism has been to ensure that a significant chunk of the population is left behind – stuck in precarious, low-paying jobs and forced to pay more for basic amenities and services – so that the richest and most powerful few can accrue ever increasing sums for themselves.

From any rational, scientific perspective, a fossil fuel-driven recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is a bad idea. By setting a course to becoming an even greater contributor to global emissions, the Australian government is helping to lock in future catastrophes that will make the current crisis seem like a mere blip on the radar. To Morrison and his like, however, none of this matters. What matters is his continuing service to big business and the rich, for whom next year’s profit and loss statements matter infinitely more than the increasing climate disaster – a disaster from which they expect their wealth to protect them.