“Almost more than talent you need tenacity, and an infinite capacity for rejection if you are to succeed.” Larry Kramer gave this advice to aspiring writers in the introduction to his 1992 play The Destiny of Me, but it could easily sum up his own life and legacy. The celebrated playwright and founder of two of the first US organisations to take on the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, died on 27 May 2020.

A friend and former rival of Kramer’s, writing in the New Yorker, fondly remembers him as “the most annoying and abrasive man in America”. Kramer had no problem calling out homophobia and injustice – but he was equally intolerant of waverers, ditherers and fence-sitters, whether they were fellow movement activists or top medical figures like Anthony Fauci.

These days, Fauci is seen as the lone voice of sanity heading up the White House’s coronavirus taskforce. In 1984, he led the federal response to the AIDS epidemic and was labelled a homophobe, a murderer and an “incompetent idiot” by Kramer. Kramer was critical of what he saw as a sluggish and disinterested governmental response to the crisis in which young gay men were dying in their thousands.

Kramer dedicated the best part of his life – often to the detriment of his artistic career – to fighting the scourge of HIV/AIDS, a plague that had taken his lovers, friends and community.

Before AIDS, Kramer had criticised gay male promiscuity and hedonism in his 1978 novel Faggots. The novel’s content – a highly critical view of post-Stonewall gay culture – and his confrontational style earned him few friends. Years later, in his 1985 autobiographical play The Normal Heart, Kramer would develop this critique but with more empathy, recognising that one of the cruelest facts of the AIDS epidemic is that it seemed to spring from the very source of gay men’s happiness.

The 1969 Stonewall riots gave rise to the Gay Liberation Movement and a flowering of radical gay politics worldwide. A decade later, the things Kramer’s generation had fought for – the right to live and love freely, to have sex and build relationships – seemed to turn to poison.

At that time, US president Ronald Reagan oversaw not only the introduction of neoliberalism, but also a conservative social backlash against the gains of the radical movements of the previous decades. For-profit healthcare and state-sanctioned homophobia created the ideal conditions for a virus like HIV to rip through gay communities in cities like New York and San Francisco.

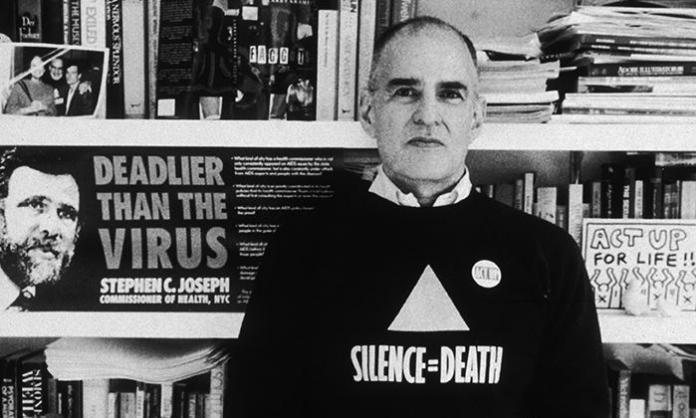

It was against this backdrop – thousands of gay men and people of colour dying from AIDS – that Kramer launched the activist organisation AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (known as ACT UP) in 1987. Kramer had previously launched the community organisation Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982, which provided health services and information. However by 1987, with the body count piling up, Kramer and other gay liberation activists felt something more radical was needed.

After its inaugural meeting attracted 300 supporters, ACT UP’s first mobilisation in March 1987 was an attempt to shut down Wall Street, the global centre of finance. ACT UP targeted the pharmaceutical companies who were simultaneously slowing down research into lifesaving drugs, while profiting off the experimental drugs that existed. Over 100 were arrested, and it was only the beginning.

Two years later, ACT UP took on the anti-gay bigot cardinal Joseph O’Connor. While O’Connor presided over mass at St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, 7,000 people attended an ACT UP protest outside. Meanwhile, Kramer and a few others infiltrated O’Connor’s service. They chained themselves to pews, threw condoms in the air and screeched “like banshees” inside, calling O’Connor a “liar” and a “murderer”. Of course, Kramer was the most outrageous. At one point he took the Holy Communion, crumbled it to pieces in his mouth and spat it on the floor. This earned Kramer and ACT UP national notoriety.

Stunts and actions like these, as well as occupying the lobbies and offices of government agencies and medical companies, street protests and other forms of direct action, turned Kramer and ACT UP into household names. In 1990, when Kramer and his fellow ACT UP members appeared on a popular daytime talkshow, he was asked by the host why he had to be so sacrilegious and aggressive. Wouldn’t this repel traditional and conservative types?

Kramer answered: “We’re ten years into an epidemic. We’re with our second president [George HW Bush] who doesn’t give a damn. We’ve tried all the quiet negotiations. We’ve tried to be good little boys and girls. We’ve tried to work within the system. There’s a new AIDS death every half hour. We are forced into this position, quite frankly. We wanted to be friends with everybody but at this point, we just wanna raise the issues. We are dying.”

It wasn’t only AIDS gay men were dying of: the epidemic led to anti-gay hysteria resulting in regular, sometimes deadly gay-bashings. Homophobia was promoted from the highest public office – Reagan famously refused to even utter the word “AIDS” on television, let alone fund vital treatment and research. So deep was Reagan’s bigotry that when the Hollywood actor and longtime Reagan family friend Rock Hudson discovered he was dying of AIDS, the Reagans refused to see him even one last time.

Kramer and ACT UP’s activism were instrumental in forcing the US government to invest in drug research, and to provide services for those living with HIV and AIDS. Many ACT UP members were themselves HIV positive. People joined the organisation knowing they might only have a few months left. Yet they gave their lives to the struggle, and sometimes their deaths, as funerals often turned into demonstrations.

Kramer was no revolutionary but he was definitely a radical. He believed in activism to force change, and the importance of taking a stand even if at first you are in a minority. He understood how this could change opinions, push society to the left and inspire others to act.

In 2002, Fauci – by now a friend of Kramer’s – reflected on Kramer’s contribution to AIDS research: “In American medicine, there are two eras. Before Larry and after Larry… There is no question in my mind that Larry helped change medicine in this country. And he helped change it for the better.”

Larry Kramer’s exit has left the world a poorer place. May his tenacity inspire generations to come.