The Zapatista Army of National Liberation, which for several decades has controlled autonomous zones in the Mexican state of Chiapas, lives by a slogan: Para todos todo. Para nosotros nada (For everyone, everything. For us, nothing). When the Zapatistas launched an armed rebellion on New Year’s Day in 1994, the world jolted to attention, the Zapatista model of mutual aid influencing a generation in the anti-globalisation movement through the next decade.

When, in 2014, their enigmatic spokesperson subcomandante Marcos announced his imminent departure, many interpreted it as a gesture to the existence of a sort of transcendental revolutionary subject. Like the ghost of Tom Joad, the spirit of the subcomandante would, despite his absence, be discernible in every fight against injustice.

It should come as no surprise, then, that in that very same year there emerged another “true visionary committed to telling the authentic story of what it takes to craft a revolution”. Her name is Sadrah Schadel. And those are her words. About herself. Otherwise known as colonel Humility, Schadel, with her business partner Mike, took the revolution to an altogether higher plane: the El Zapatista vegan chorizo that “radically redefines mealtime”. Their plant-based journey to founding No Evil Foods – a North Carolina enterprise that turns wheat gluten into fake meat – is said to encapsulate the pair’s “dedication to giving back and working to improve systems of oppression”.

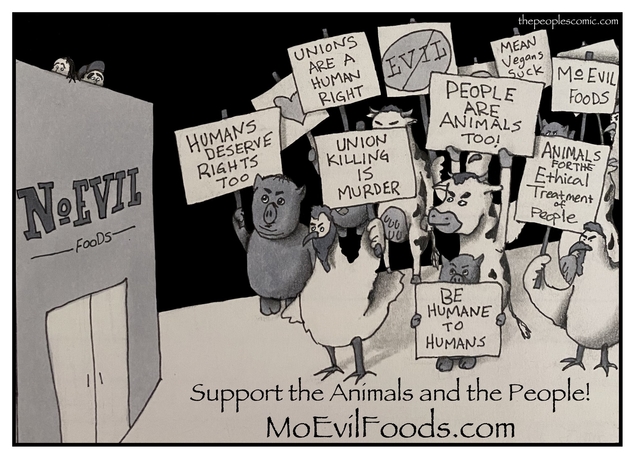

While Schadel surely thinks that “improve” means something other than “enhance”, the word choice is nevertheless apt. You see, No Evil Foods, despite using the imagery and vernacular of socialism (its fake chicken is called Comrade Cluck), is a union busting firm that has sacked or driven out exactly the sort of people you would expect the company’s image to attract – young idealistic workers wanting to make a difference.

“I really loved the job and I wanted to cement in a contract all the things that were good about the place”, Meagan Sullivan, a former employee, says over the phone from North Carolina. “It started to go downhill when management found out that we had filed with the NLRB [National Labor Relations Board, the government office through which unions are registered].”

Several employees wanted to organise the firm under the United Food and Commercial Workers International union. But No Evil held rounds of “captive meetings” to intimidate the workforce out of formally establishing a union. (In the United States, unions can be registered at a workplace only if a majority of employees vote to do so in a secret ballot.) In secretly recorded audio of the sessions, managers can be heard telling employees that the union was interested only in taking members’ money and contracting away their individual rights, that it could bring charges against and try its members and former members over hearsay, that being in a union would make it more difficult to stamp out sexual harassment in the workplace, and that forming a union at No Evil would put at risk both the viability of their mission and the security of everyone’s jobs.

“The captive meetings were intense, extremely hostile”, Meagan says. “There were five or six people from upper management – they would have the meetings every other day. We attended seven.” That’s somewhere between seven and 14 hours of anti-union argumentation. It may not have been as taxing as months of training in the steaming jungles of southern Mexico, but, in the small hamlet of Weaverville to the west of Pisgah National Forest, No Evil’s management tirelessly propagandised for their cause.

The reason for the meetings, the company said, was to make sure all employees could make an informed decision when it came time to vote. But “whenever pro-union material was brought into the workplace, management would throw it in the garbage”, Meagan says. Ultimately, the company’s fear campaign was successful. That wasn’t the end of it, though. More than 20 workers have quit or have been fired since the union vote on 13 February, according to Jon Reynolds, who was also part of the organising drive.

In March, as the pandemic was surging, employees were given just 24 hours to sign a declaration of their intent to continue working, to temporarily stop working, or stop working altogether. Those choosing to keep working would receive a temporary pay increase of $1.50 per hour – but only if they maintained a perfect attendance record for three months. Those wanting to stop working but come back when safe to do so would have to apply for a position like anyone else looking for work in the economic depression. Those choosing not to come back would receive severance pay only on the condition that they signed a release freeing the company of any claims against it. Anyone who didn’t respond in time was marked as “voluntary resignation”.

With the deadly virus spreading, the “comrades” at No Evil sent a message to their most vulnerable employees: you are on your own. Some of the pro-union people stayed on and kept organising, this time to make the pay increase permanent and unconditional. While they won a small victory – the offer was increased to $2.25 – the company again retaliated. Jon, who had petitioned for the pay rise, was fired on May Day, of all occasions. The official reason for being let go? “Not taking social distancing seriously and for my performance lacking”, he says. “But Meagan and I were the ones who brought up the question of social distancing in the first place because we didn’t think the place was operating safely.”

Meagan, targeted for allegedly being one minute late for a shift, was asked to sign a confession. Another worker involved in the unionisation drive, Cortne, was fired a week before Jon because her pants were an inch too high at the ankle. She then waited six weeks to receive unemployment entitlements because, she says, the company challenged her case for receiving them. It was a clear pattern of punitive retribution.

“No Evil leveraged their image as a progressive company against the drive to unionise. Then they fired people because they were trying to organise. And they fired us in the middle of this pandemic without thinking twice about it”, Cortne says via phone. “The pettiness of management is not something I’ve experienced before.”

“Like wildfire, the Plant Meat rebellion spreads”, No Evil Foods’ website declares. In this case, to more than 5,000 retail outlets across the United States. You don’t get that sort of coverage by being a bleeding heart or daydreaming about hazard pay, that’s for sure. On the contrary, you need support from at least five venture capitalist outfits to complete the revolution. No wonder the Zapatistas never made it further than Chiapas.

--------------------

More information about the ongoing campaign for justice at No Evil Foods: