The 1970s promised so much—gay liberation had broken through homophobic hate, and life for LGBTI people was being transformed. As the 1980s arrived, so too did homosexual law reform, anti-discrimination laws, gay media and a thriving gay culture. But then came a mysterious disease that seemed to target gay men, its cause and mode of transmission unknown. Suddenly, gay sexuality was stigmatised all over again, with panicky headlines referencing a “gay plague” or, in the case of Melbourne’s Truth newspaper, the overtly homophobic “Die, you deviate”. Talk of forced quarantining, compulsory testing and surveillance of gay men was everywhere.

In the US, President Ronald Reagan refused to utter the word AIDS in the first four years of the crisis, despite 60,000 being infected and 28,000 dying. As late as 1987, the US Congress banned the use of federal funds for AIDS prevention or for education that was in any way supportive of homosexuality. “Nobody left those years untouched”, wrote journalist David France, “not only the mass deaths—100,000 in New York alone—but also the foul truths that a microscopic virus had revealed about American culture: politicians who welcomed the plague as proof of God’s will, doctors who refused the victims medical care, ministers and often parents who withheld all but the barest shudder of grief”.

But LGBTI people were coming out of a period of activism and, despite the initial shock, were prepared publicly and defiantly to fight any attempt to take away what they had won. While the battle in the US and the UK was hampered by government homophobia, in Australia, as Nick Cook’s Fighting for Our Lives: The History of a Community Response to AIDS describes, the “buggers, druggies and prozzies” (those most impacted) were able to play an active role in shaping effective HIV/AIDS policy. In the end, and thanks largely to this activism, Australia became one of the few countries that avoided an epidemic among injecting drug users and reportedly no HIV transmission from a female sex worker to a client.

Three factors delivered this result. First and foremost was the preparedness of LGBTI people to organise and fight—as did their counterparts around the world in what became an international movement. The second was the election of a federal Labor government in 1983, and the appointment of Neal Blewett and later Brian Howe as health ministers, both of whom were prepared to listen to and involve grassroots organisations in the government’s HIV/AIDS response. Finally, there was the health policy itself, which focused more on community-based prevention and support, rather than solely medical solutions. Recent examples of women’s grassroots-run health care and rape crisis centres were the prototypes for this community-based response.

In May 1983, when the possibility of AIDS being a blood-based disease was first becoming public, the director of the Sydney Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service called on “promiscuous” gay men not to donate, in what was perceived to be a homophobic slur. Three days later, activists picketed with “Ban the Bigot, Not the Blood” placards, after which the New South Wales AIDS Action Committee (ACON) was formed.

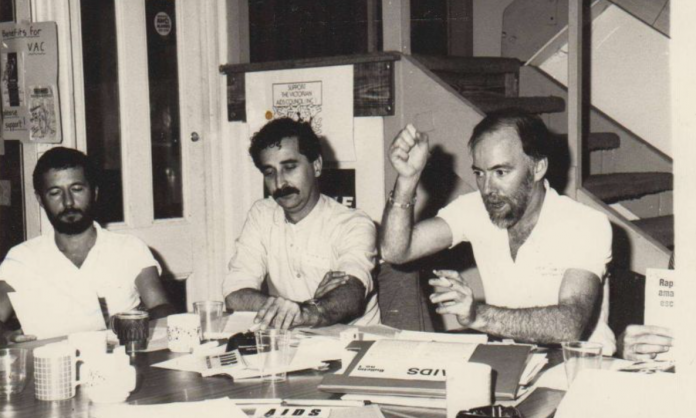

ACON was determined that LGBTI voices would be part of policy making, demanding that the Wran state Labor government set up a ministerial advisory group that it would be a part of. Activism was also central to the activity of groups like ACON. Shortly after ACON was formed in New South Wales, 700 people crowded into a meeting room in Victoria to hear mostly bad news from a panel of doctors. As the mood darkened, socialist activist Alison Thorne took the microphone and argued, “We have to do something! Let’s have a meeting and start to organise”. The next month, the Victorian AIDS Action Committee (VAC) was formed and the organising began.

By September, activists had met with the federal health minister and medical researchers, both of whom had a vexed relationship with LGBTI people. Before the gay liberation movement, the medical profession had routinely treated homosexuality as a disease, and the state had criminalised gay male sex. Only one state had decriminalised male homosexuality when AIDS hit Australia in 1982. Groups like the VAC ensured that health and government officials didn’t dominate the political response to AIDS, VAC’s Adam Carr insisting: “We reject any suggestions that AIDS is in any way a gay plague ... We reject any suggestions that homosexuals or any other minority groups are responsible for the outbreak of this disease. We will defend the gay community from these attacks”.

Though there were few active cases in Australia in 1983, the campaign was off to a determined start, issuing press releases, getting serious coverage in the gay media and attempting to reach out to health professionals and state and federal politicians. However, in 1984, there was a sharp turn when the Queensland government, a bunch of reactionaries led by Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, announced the death of three babies after developing AIDS from blood transfusions sourced to a gay man. The press went ballistic and homophobia exploded.

Bjelke-Petersen called gay men “insulting, evil animals”, implied they would knowingly infect others with HIV, refused to set up testing and treatment facilities and railed against sex education in schools. Angus Innes, a Queensland Liberal MP, argued in parliament that any gay men who gave blood that resulted in deaths should be charged with manslaughter, to protect “innocent people” from their “selfish lifestyle”.

The federal government, by contrast, responded by establishing a national advisory body involving health ministers, doctors and nurses, the Haemophilia Foundation and ACON and VAC representatives. By the end of the year, the New South Wales, Victorian and federal governments had started funding various non-government groups such as ACON, VAC and prostitute and drug user advocacy groups to enable them to deliver prevention and education initiatives at a grassroots level.

While this was welcome, there was reason to be wary. A taskforce set up under the new advisory body was dominated by doctors, who tended to be focused on the medical rather than social consequences of government policy. As late as 1988, the Australian Medical Association declared that while AIDS had “major social and moral implications ... it is an infectious disease and the medical profession has a central role in its prevention and management”. The AMA favoured widespread testing and compulsory health department notification of cases. While not unreasonable on the face of it, the problem was that this failed to acknowledge that gay male sex was still criminalised in several states, and concern about leaked information and consequent victimisation would have kept many away, undermining the value of testing. Adding to the tensions, in 1990, AMA president Bruce Shepherd accused the federal health minister of being gay, questioned his impartiality and implied HIV/AIDS would get out of control under his leadership, none of which encouraged gay men to have confidence in the AMA’s approach.

The AMA was not alone in considering compulsory disease control measures; state governments also did, leading to some stormy meetings with activists. In Victoria, such moves were rebuffed and in 1987 the government amended the Equal Opportunity Act to make it illegal to discriminate against people with HIV/AIDS.

Tensions over how the battle against AIDS would be fought were rife. Would it be a more discreet educational campaign with most of the focus on influencing government and health professionals through advisory bodies? Or something more confrontational and daring, less focused on fear and more on a sex-positive, authority-challenging campaign?

The activists chose the latter. Of course, there was still cooperation through the advisory groups, but ACON and VAC and other activists also looked to a campaign focused on making safe sex sexy. “We invented daring, community-led safe sex campaigns”, Nick Cook writes, “that spoke frankly to people in their own sexual vernaculars, explaining how to fuck safely in the midst of a sexual epidemic”. One early poster declared “Great Sex! Don’t let AIDS spoil it”. This openly pro-sex safety message, which put a positive spin on what could easily have become a source of fear and shame, persisted despite government opposition. Above all it was the urgency of dealing with a fatal epidemic that called forth a daring campaign and prompted many to challenge long-held prejudices and social assumptions in the course of fighting to stop its spread.

The workplace was another potentially fraught battleground. The Australian Council of Trade Unions adopted an anti-discrimination policy that was taken up by affiliated unions and which helped prevent a homophobic backlash. Networks of unionists were propelled into action by many of the activists in the education, health-care and public transport sectors, where some of the first HIV/AIDS positive workers were diagnosed. It wasn’t just workplace issues unionists campaigned about, but also access to public health care, affordable housing, welfare and other services. Blue collar unions such as the plumbing and construction unions were at the forefront of educating their members about AIDS and driving a community response. The Australian Tramway and Motor Omnibus Employees Association made a panel on the main Australian AIDS quilt for union members who had died of AIDS.

New issues arose as the crisis progressed. In 1989, as some treatments became available but were kept prohibitively expensive by pharmaceutical giants’ profiteering, once again grassroots action was called for. In the US, a small group dressed in suits with fake IDs invaded the New York Stock Exchange, presenting startled traders with demands that drug companies make HIV/AIDS drugs affordable. Other actions, such as sit-ins, occupations of company headquarters and the hanging of effigies of drug regulation administrators in public, kept attention on the issue.

Drug availability was a key battleground in Australia as well. ACT-UP groups—modelled on the US AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—formed around the country in 1990. Adopting the slogan Silence=Death, the group went on the offensive. Uproar followed the replacement of flowers with wooden crosses in Melbourne’s iconic floral clock, but undaunted activists went on to abseil into question time in federal parliament, paint-bomb health minister Brian Howe’s office and hold a kiss-in in the Bourke Street Mall after the government banned an AIDS poster showing two men kissing.

They were also getting out serious information about treatment by leafleting bars and otherwise having a presence in the LGBTI scene. On 6 June 1991, mass action under the clocks at Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station highlighted a D-Day ultimatum to the federal government to speed up drug approvals.

One effective but little-known action showcases some of the daring of the campaign as well as the involvement of unions. ACT-UP approached the Victorian branch of the Transport Workers’ Union to call for support for their attempt to force the drug companies to release treatment drugs. Two of the activists then approached the company medical director. After listening to his platitudes about how the company was doing all it could, the activists put a proposition to him. If the drugs weren’t made available, there’d be a consumer boycott on the company’s other products, such as the cleaning fluid Windex, and a picket line would be set up at the three warehouses that stored all its products. This picket line, they informed him, would not be crossed by transport workers. The director quickly assured them that the company could arrange more rapid delivery, pleading, “Don’t bring in the unions!”

This sort of action forced governments and the companies to respond to the needs of those living with HIV/AIDS. By once more “coming out” to challenge homophobia—by publicly politicising what could have been a hushed-up response to a frightening infectious disease, a higher death toll, destitution for many and victim-blaming—LGBTI people themselves helped to change attitudes. Homosexuality was decriminalised in three states, and school sexuality studies included HIV/AIDS material, all during the time the pandemic was sweeping through the world. People living with HIV/AIDS and their supporters recast the negative stereotypes, turning people from victims and sufferers or people dying from the disease, to people living with HIV/AIDS. There was also a longer-term impact on research related to the disease, focusing more on health, lifestyle, safe sex, services and treatment, rather than solely an illness model.

HIV/AIDS destroyed countless lives and devastated many more. But the efforts of activists helped to limit the toll and prevented the disease destroying all the progress that had been made against homophobia prior to its arrival. Their courage and determination in terrible circumstances set the tone for future LGBTI struggles and should never be forgotten.