The US military establishment will breathe a sigh of relief at Joe Biden’s victory in the presidential election. Nearly 800 former high-ranking military and security officials penned an open letter in support of the Democratic candidate during the campaign. A who’s who of former generals, ambassadors, admirals and senior national security advisers—from former Secretary of State Madeline Albright to four-star admiral and Bush-era Deputy Homeland Security Advisor Steve Abbot—backed Biden as the best bet to revive US power. A month earlier, 70 national security officials who served in Republican administrations threw their weight behind Biden (the list soon grew to 130), arguing that, on foreign policy, Trump “has failed our country”.

Why was Biden the war criminals’ candidate of choice? The foreign policy chaos and controversy of the Trump years were a symptom of a global superpower in relative decline, with no real strategy out of the quagmire.

The US empire is at a turning point. It is the world’s undisputed superpower; its reach is global, both militarily and economically. The US has been the world’s largest economy since 1871, and its military has close to 800 installations in 80 countries around the world. But today, it is facing a growing economic rival in China, and several lesser powers challenging its ability to call the shots in every corner of the globe, most notably Iran and Russia.

The War on Terror, launched by the administration of George W. Bush, resulted in the invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. It killed more than a million people and cost upwards of US$2.4 trillion, according to the Congressional Budget Office. For the people of the Middle East, it was a massacre. For US empire, it was a disaster. The destabilisation of Iraq led to the expansion of Iranian influence across the region, rather than the regime change in Tehran the Pentagon dreamed of. The intervention in Iraq was meant to secure US dominance. It instead exposed the weaknesses and limits of US power right at the moment when China’s dramatic economic expansion was beginning.

Tensions between the US and China have been increasing for years. Since its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has built its economic power, its diplomatic power and its military power, while the US became bogged down in endless wars and suffered economic crisis and depression with the 2008 financial crisis.

Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia”, with its plan to increase US naval forces in the Asia-Pacific, was a signal that the US ruling class wanted to contain and encircle China. Obama’s then classified Air-Sea Battle doctrine was an effort to create an operational plan for a possible military confrontation. Leaked cables made public by WikiLeaks reveal that Australia was in lockstep with US imperial strategy. In conversation with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2009, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd confirmed Australia’s willingness to “deploy force if everything goes wrong”. But Obama’s strategy was too little too late for containment. China became more aggressive in pressing claims in the South China Sea while beginning to close the enormous gap in military capabilities with the United States, engaging in the most rapid peacetime arms build-up in history.

Under Trump, these tensions further increased. Trump’s confrontational rhetoric and trade war were a sharp break from the decades-long US strategy of integrating China into the international liberal order. Since the Republican administration of Richard Nixon—who in 1972 became the first US president to visit Beijing—the US ruling class thought it could ensure global supremacy by incorporating China into the world system. For a while, it appeared to work. China became the world’s sweatshop and a key site of investment for US companies such as Apple and General Motors. But the strategy could be mutually enriching for only so long. Today, China is leveraging its meteoric growth to challenge the United States’ leadership in the Asia-Pacific.

Obama’s signature containment strategy was the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The TPP would have been the largest free trade deal in history, lowering tariffs and other non-tariff barriers to trade between eleven Pacific countries and the US. Its goal was to lock out China and further integrate Pacific countries with the US economy. Obama’s Defense Secretary Ashton Carter said that the TPP was “as important ... as another aircraft carrier”.

But just a few years later, Donald Trump tore up the TPP. The move was at odds with the consensus among the US economic and military elite, but the new president had his own ideas about how to contain China. Trump railed against the US trade deficit, accused Beijing of currency manipulation and, as Obama did, of stealing technology from US companies. In the 2019 State of the Union address he said, “We are now making it clear to China that after years of targeting our industries and stealing our intellectual property, the theft of American jobs and wealth has come to an end”.

By August this year, Trump had slapped tariffs on $550 billion of Chinese goods, with a targeted campaign against tech giant Huawei, which had been tipped to overtake Apple in global phone sales. While Republican and Democratic politicians have backed a hardline approach to China, Trump’s erratic protectionist approach to trade has alienated large sections of the capitalist class otherwise happy with domestic tax cuts and deregulation. A Bloomberg Economics report, released before the pandemic gripped the country, estimated that the escalating tariffs on China would cost the US economy $316 billion by the end of this year.

More worryingly for the US establishment, Trump adopted a dismissive attitude towards US allies, particularly the European Union. Trump prided himself on his ability to cut deals with other nations that favoured the US. He signalled that the multilateral approach to trade was over when he tore up the TPP, and followed that by applying tariffs on German cars, Canadian steel and French luxury goods. For much of the US elite, these moves have simply created a void that Beijing is attempting to fill with its own free trade deals and the $1 trillion Belt and Road initiative, which aims to incorporate more than 138 countries into trade routes and production chains centred on China.

The International Monetary Fund, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the UN and other international institutions project US dominance by drawing allied nations behind US leadership. Trump’s presidency delegitimised or sidelined those institutions as he focused on an “America first” posture. The military establishment believes that this has threatened, rather than strengthened, US power—although there is now an acknowledgement that those institutions failed to keep China in check, something a Biden presidency will also grapple with.

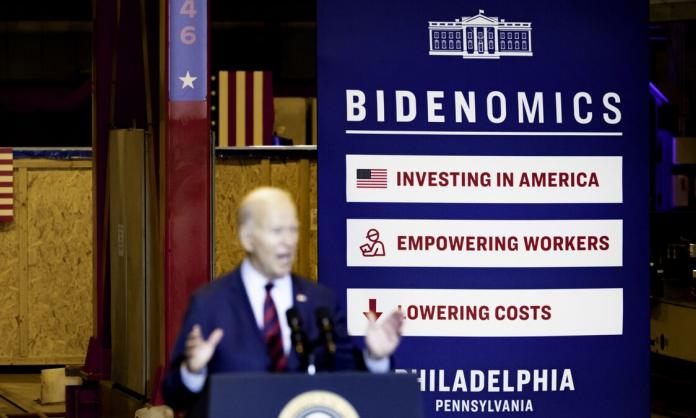

The war criminals hope that Biden will restore political legitimacy to the office by rehabilitating the liberal ideology that manufactures consent for American imperialism, pitching US aggression as necessary to “make the world safe for democracy” and defending the “rules-based liberal world order”. Above all, the US establishment hopes that Biden will restore relationships with US allies and construct a coalition of nations to confront China, after a disastrous four years that called into question US global leadership. As the National Security Leaders for Biden open letter bemoaned: “Our allies no longer trust or respect us, and our enemies no longer fear us”.

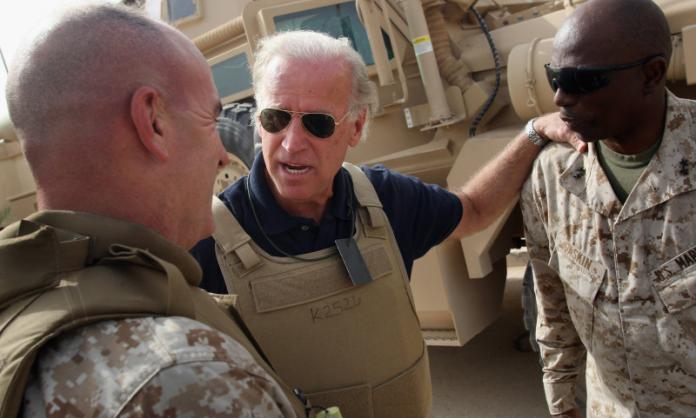

Biden has a proven record as a hawkish proponent of US empire. For decades, he served on the Senate foreign relations committee. He was an early proponent of the expansion of NATO to project US influence into the former eastern bloc after the fall of the USSR. He backed US intervention in the Balkan war, supported the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, voted for the war on Iraq in 2003 and, as vice president, backed the US intervention in Libya.

There is consensus within the US ruling class over the need to “get tough” with China. The military establishment expects Biden to turn the screws. On the campaign trail, he accused Trump of “getting played” by Chinese President Xi Jinping, whom he called a “thug”. This is consistent with Democratic Party practice in the Congress, which is to criticise Trump for not being tough enough. Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer, for example, accused Trump of “selling out” by cutting a trade deal with China. Schumer also spearheaded legislation to implement bans on Huawei when Trump appeared to back down.

Since his first days in Congress, Biden has also made a name for himself as a staunch supporter of the apartheid state of Israel. According to Israeli publication Haaretz, Biden is said to have a “real friendship” with Israel’s far-right president, Benjamin Netanyahu. He was vice president when the US signed a $38 billion military aid deal with Netanyahu, which the State Department called the “single largest pledge of bilateral military assistance in US history”. So while Trump pushed pro-Israeli rhetoric far to the right, abandoning any pretence of support for Palestinian statehood, Biden put his money where his mouth is when it came to propping up Israeli apartheid in Palestine.

On Afghanistan, Biden may prove to be to the right of Trump. As vice president, he supported an enduring US military presence in the country. Trump, by contrast, shocked the US military when he announced on Twitter that he wants all troops out by Christmas. In contrast, Biden in an interview with Stars and Stripes, a military newspaper, said he would maintain a troop presence in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Anti-imperialists need to judge Biden by his blood-soaked record in Congress and by the company he keeps. The bulk of the US military establishment has backed Biden precisely because they think his multilateral approach will restore credibility to US interventions. It’s for this reason that Forbes magazine senior contributor Loren Thompson predicted last month: “A Biden presidency ... would be more likely to use US military forces overseas than President Trump has been”.

Global capitalism is facing a profound crisis that is reshaping international relations and putting pressure on the fault lines of existing conflicts. Open imperialist rivalry will be a feature of the coming period, along with wars over regional disputes. There is no length to which the US ruling class won’t go to safeguard its position as global superpower. And Joe Biden is the commander-in-chief. He is now the most dangerous man in the world.