Crises tumble around our world, challenging certainties, destabilising regimes and shaking-up people’s understanding of society. Out of the disruption comes political analysis and organising, a battle between left and right—liberation or barbarism. Alongside the organisers and agitators are the writers, poets, filmmakers, photographers and artists whose work documents our world of change, forging iconic images that provide fuel for the struggle.

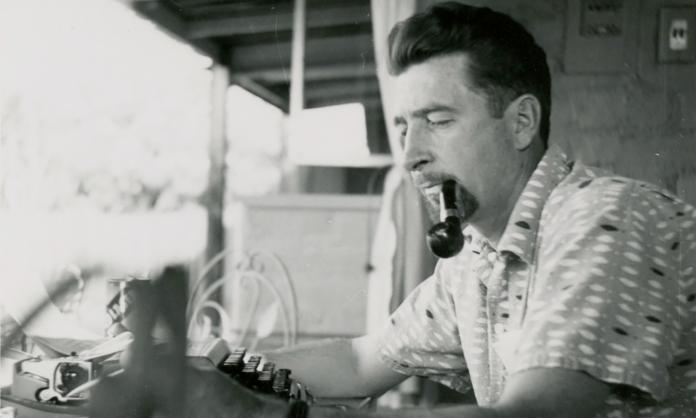

Among the greatest such figures of the 20th century was US poet Thomas McGrath. McGrath was born in 1916 into an Irish farming community in North Dakota. His poems are products and markers of some of the most significant periods and events of the US workers’ movement in the middle decades of the century.

McGrath is a poet of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, of the pre-World War II militancy and post-war sell-outs on the New York waterfront, of the initial soaring hopes and ultimate crushing defeat of the Spanish revolution, of the radical life of members and supporters of the US Communist Party, and of the dark days of the anti-communist witch-hunts of McCarthyism. Through it all McGrath maintained his hope for the future, and faith in the power of the working class to build a better world. His poems are, as his friend Dale Jacobsen writes, “flames cast against the darkness”.

The rural North Dakota of McGrath’s childhood wasn’t so much redneck as just plain red—influenced by the militant class struggle politics of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies) and the earlier left-populism of the Farmers Alliance. The Alliance won power in the state for a brief period in the late 19th century and passed a number of significant reforms. It created a state bank and state-owned grain elevators to stop price gouging by private capitalists, and it legalised strikes and brought in stricter safety regulations in the mines.

The Wobblies were particularly popular with itinerant farm, mining and timber workers. McGrath’s earliest working years were spent among timber workers from a multitude of countries. In one poem, he recalls the radical conversations:

The talk flickered like fires.

The gist of it was, it was a bad world and we were the boys to change it.

And it was a bad world; and we might have.

Later they talk of the hunger marchers who’d occupied the local city hall:

Bricklayer, watchmaker, Communists, hoped they were building

The new society, inside the shell of the old ...

Another poem describes a strike during the harvest, and references the popular Wobblies’ image of the worker with folded arms:

The strike started then. Why then I don’t know.

Cal spoke for the men ...

There were strikes on other rigs that day, most of them lost,

And, on the second night, a few barns burned.

After that a scattering of flat alky bottles,

Gasoline filled, were found, buried in bundles.

“The folded arms of the workers.”

Just before World War II, McGrath worked on the New York waterfront. Writing in the TriQuarterly Magazine about the political atmosphere of the docks during McGrath’s time there, Terrence Des Pres describes how “the fight for reform went forward on the piers and in the bars and walk-ups of Chelsea”. Nonetheless, despite the radicalism of many dock workers, being a communist wasn’t always easy. To be a red on the waterfront, Des Pres goes on, “was to be natural prey of goon squads patrolling ... for the bosses and the racketeers”.

During his time on the docks McGrath met the likes of “Packy O’Sullivan”:

‘After the war we'll get them,’ Packy says.

...

‘After

The war we'll shake the bosses' tree till the money rains

Like crab-apples. Faith, we'll put them under the ground.’

After the war.

Faith.

Left wing of the IRA

That one,

Still dreaming of dynamite.

I nod my head.

But after the war the bosses had won and Packy O’Sullivan and his like were gone. McGrath found his friends dead or departed, the pre-war radicalism of the National Maritime Union (NMU) bought off and entangled with the racketeers and gangs, and a new breed of “labor fakers” running the show. McGrath’s words turn bitter as he describes how:

The talking walls had forgotten our names, down at the Front,

Where the seamen fought and the longshoremen struck the great ships

In the War of the Poor.

And the NMU had moved to the deep south

(Below Fourteenth) and built them a kind of Moorish whorehouse

For a union hall. And the lads who built that union are gone.

Dead. Deep sixed. Read out of the books. Expelled ...

McGrath had enlisted in 1942 and he spent most of the war at a provisions base on the remote Aleutian Islands—effectively sidelined from the front along with a bunch of other radicals. Following the war he moved to Hollywood. With the beginning of the Cold War with Russia in the late 1940s, the political atmosphere took a sharp turn for the worse. “Now, in the chill streets”, McGrath wrote, “I hear the hunting and the long thunder of money”.

In 1953 McGrath—by then lecturing at the State University of Los Angeles—was hauled before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He refused to answer any questions about himself or to betray his friends. “Poets have been notorious non-cooperators where committees of this sort are concerned”, he wrote. “I would prefer to take my stand with Marvell, Blake, Shelley and García Lorca.”

His non-cooperation got him fired from his lecturing job. Outraged, students and fellow academics formed a committee to defend academic freedom, staged several protests, and arranged to publish a book of his poems—Witness to the Times!—to honour McGrath and record the moment. In the book’s foreword McGrath wrote that “A teacher who will tack and turn with every shift of the political wind cannot be a good teacher. I have never done this myself, nor will I ever”.

Like many communists of that era, McGrath was blacklisted, and unable to find work for the remainder of the 1950s. It was during that time that he began writing his book length poem, Letter to an Imaginary Friend—a broad sweep of his life. The critic Roger Mitchell described it, in the American Book Review, as in part, “a personalized history of 'the generous wish' of the far Left in our country, tender and raucous, damning and hoping, a poem written in an uncongenial time in which he writhes and rages to keep the hope of ‘the solidarity/In the circle of hungry equals’ alive”.

McGrath saw how the anti-communist hysteria of McCarthyism led so many to choose the side of the ruling class, and the impact this had on the diminishing ranks of the left. He wrote of “the internal collapse of that culture of the Left as it disappeared into betrayals, self-accusation and disavowals, ‘do-it-yourself’ Judas kits ... the predicament of any dissidents isolated within a conformist society”. He nevertheless embraced the role of the isolated dissident, seeing it as one of remembering, documenting, and preparing for future battles.

In the dark days of the left’s isolation in the 1950s and early ‘60s he was unafraid to look the dispiriting reality in the face. He railed against those who argued for more “positivity”:

Comrades you must be more positive!

You must have confidence in the international working class movement!

And what if that movement was collapsing in ruins and bad faith all around us,

Did not poets then have the duty to warn?

In particular McGrath opposed the US Communist Party’s Popular Front strategy which he saw as an abandonment of revolutionary activity. Revolutionaries, he lamented, were now supposed to believe that “somehow or other there was going to be this wonderful accord between the powers who had defeated the Nazis. And that one might go forward with a kind of ... benevolent gradualism. Which I thought was total bullshit”.

He mourned the loss of revolutionary politics which left a “terrible emptiness in the whole life of the country”, but pledged himself to fight on:

But where is the steering star

Where

The Plow? The Wheel?

Made this song in a bad time ...

No revolutionary song now, no revolutionary

Party

Sell out

False consciousness

Yet I will

Sing

For those poor

For the victory still to come.

Many other poems from the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s bear witness to his ongoing revolt against the barbarism of capitalist society. His work covers Auschwitz, the Korean and Vietnam wars, Chile and El Salvador. Because Nothing Endures is a protest against the relentless freeway building in Los Angeles—the construction of one of which, Interstate 5, demolished McGrath’s entire neighbourhood.

He returns again and again to war—the losses, the threat of nuclear war, and the way it is celebrated. One particularly bitter reality he confronted was the fact that his beloved North Dakota came to be a major centre for the US’s nuclear arsenal. At one point the concentration of nuclear weapons kept there was so high that, if it seceded from the US, the state would have been the third most powerful nuclear power in the world—a state, as McGrath put it, “where all money is armed”.

Later in his life he was also forced to confront the reality that the world of his childhood in rural North Dakota was built—as recently as the generation of his parents and grandparents—through the dispossession of the original Sioux people. White America, he wrote:

... gained a freedom by taking theirs ...

We learned the pious and patriotic art of extermination

And no uneasy conscience where the man’s skin was the wrong

Color; or his vowels shaped wrong; or his haircut; or his country possessed of

Oil; or holding the wrong place on the map—whatever

The master races wants it will find good reasons for having.

Elsewhere, in words that will resonate with readers in Australia confronting our own history of dispossession and genocide, he pointed to the fundamental dishonesty of the myth of the “frontier”, of:

... the deep, heroic and dishonest past

Of the national myth of the frontier spirit and the free West—

Oh, nightmare, nightmare, dream and despair and dream!

McGrath welcomed the radicalisation of the 1960s and early 70s, but he wasn’t carried away totally by the moment. He continued to foreground the history of the US workers’ movement, and the lessons that could be drawn from it. He pointed to the economic realities and the entrenched power of the rich—the fact that the banks wouldn’t simply volunteer to be socialised in the name of brotherly love.

In interviews in TriQuarterly Magazine, McGrath explained how the crises and uprisings of each historic period can open people’s eyes to the reality of class society and the opposing sides of the class struggle. Finally, McGrath said, you have to choose: “like the old song says, ‘which side are you on?’”. He didn’t believe, however, in the inevitability of revolution. Instead, he thought, you needed organisation—a party like the Bolsheviks which he saw as being “one of the most heroic revolutionary organisations that has ever existed”. He retained the conviction that, despite every defeat, it is the last battle that counts—that is the one we have to win.

McGrath wrote some 30 books of poems, two novels, two books for children, and 25 scripts for feature and documentary films. The Movie at the End of the World—made in 1982—is a documentary about McGrath which takes its name from one of his books of poetry. Throughout his whole life, despite the many disappointments and defeats, his revolutionary spirit never dimmed. As Robert Blei, writing at Poetry Dispatch, put it, “There are a lot of writers who claim to be revolutionaries. A lot of talk. A lot of dramatics. A lot of words. But damn few who lay it on the line the way McGrath did”.