We’re looking out on tree-studded pasture, covered in lush, bright green grass. Thick bushland and the golden cliffs of the Hunter Valley escarpment tower above us. It’s early March 2020, and I’ve just finished a drive that’s taken me through the Latrobe Valley, the Illawarra and now to the lower Hunter. For a couple of weeks, I’ve been talking about working life and climate change with workers from the coal mining, power and steel industries.

On the way, I’ve passed hundreds of kilometres of burned-out bush from Australia’s apocalyptic bushfire season. North of Mallacoota on the Pacific Highway, for hours, the view from the highway was nothing but scorched forest.

The catastrophic fires, and the record-breaking drought that fed them, were a consequence of only about one degree Celsius of global warming. Even if all the Paris Climate Accord commitments are met (which they won’t be), we’re heading to more than twice this level of heating. I’m seeing not just a one-off disaster, but a view of our possible future.

So it’s a sight for sore eyes to find the sun breaking across rolling green hills, warming the escarpment to a golden glow as I drive from Newcastle to the Hunter Valley on a grey morning.

“What a beautiful place!”, I almost shout, as I climb out of the car and greet Alan, the father of a friend. He’s agreed to introduce me to a couple of his neighbours, past and present mine workers.

Alan is a generous and welcoming host. But there’s no trace of a smile on his face as he replies: “A month ago it looked like hell”.

A retired teacher, Alan is part of a Rural Fire Service brigade that spent four months fighting the bushfires—including the Gospers Mountain Fire, reported to be the largest single fire in Australian history, as it roared through half a million hectares of tinder-dry bush. The Corrabare State Forest fire was finally stopped just a few kilometres away, just over the ridge behind us, when the efforts of an exhausted army of volunteer firefighters were aided by a wind change and a deluge of unseasonal January rain.

For Alan, there’s no doubting climate science. He doesn’t buy the Murdoch/Morrison spin that fuel loads, rather than climate change, were responsible: “Of course, on any given day, with given conditions, if you have more fuel you’ll get a bigger fire. But I remind people in my brigade that our worst day—the day when I was really scared we were going to lose a firefighter—was in a setting like this”. He nods at the park-like rolling green hills spread out below us, studded with occasional trees.

By this time, Alan has welcomed me in and we’re seated on the porch, overlooking the beautiful vista. “You’re here to talk about coal”, Alan reminds me. “Well, you’re sitting on it.” The coal-rich countryside around us is in the federal seat of Hunter, the centre of the controversy raging over coal and climate in Australian politics.

The electorate is home to a big chunk of the Hunter Valley Coal Chain, an extraordinary logistics network connecting a string of 40 mines, up to 450 kilometres inland, to the world’s biggest coal terminal at the Port of Newcastle. Four giant coal-fired power stations in the region provide the bulk of New South Wales’ electricity. Coal and power are still significant employers—perhaps 9,000 jobs in the electorate of Hunter—and they cast a long political shadow.

Joel Fitzgibbon, the sitting Labor MP, got the fright of his political life on election night in May 2019 when his primary vote crashed from 52 percent to 38 percent. Stuart Bonds, the first-time candidate for One Nation, got a first-preference vote of 22 percent. Fitzgibbon got over the line only because a third of Bonds’ preferences flowed to him.

There were similar swings against Labor in two regional Queensland seats where the development of the Adani coal mine was a big issue. In the wake of the election, there has been a lot of chatter—not least from Fitzgibbon—that Labor’s supposedly progressive policy on climate cost the party the election.

This doesn’t really stack up. After all, Labor was unable to win the seats it needed not just in the coal districts but in suburban Melbourne and Brisbane, in South Australia (with not a single coal mine), in Tasmania or pretty much anywhere else.

Regardless of that, much of the commentary since the election has been some version of: sneering greenie inner-city elites rejected by blue-collar workers in regional areas, due to a sensible attachment to coal and high-paying coal jobs. A suspicion of this narrative is what has prompted my road trip.

The first of Alan’s neighbours arrives. Jason works in a coal mine, and we chat about the challenges of working underground, the ups and downs of the industry, the succession of mine owners and their more or less aggressive stances towards the unions.

Jason describes the daily banter at work. One of his workmates is a staunch One Nation supporter, one is a Green. Everyone digs at each other, he says, without there being any real offence given or taken. I ask him: when the discussion comes around to climate change, what percentage of his workmates accept the scientific orthodoxy? Jason thinks for a second: “I don’t think any of the younger guys, like under 40, would doubt the science”.

“Really?”, I blurt out in surprise.

Jason has a slightly startled reaction to this—clearly he’s surprised at my surprise. “Yeah of course, no-one doubts the science. Why, is that not expected or something?”

I laugh and explain. I’ve been found out accepting a stereotype—of regional blue-collar workers rejecting mainstream climate science—that I’ve driven 1,200 kilometres to challenge.

This stereotype seems genuinely strange to Jason. Climate change can certainly be a controversial topic: he mentions a social occasion where an off-hand remark “got a couple of people really offended, really emotional”. But any idea that this is the consensus around here is clearly news to Jason.

We keep chatting as Bill, another of Alan’s neighbours, drops in. Bill retired 20 years ago after working underground for 28 years. Bill served a stint as president of one of the local lodges of the Miners’ Federation, now part of the CFMMEU Mining and Energy Division.

Alan starts us off by asking Bill about one of the four mines he had worked in. “Didn’t like that one. Too rough for me.” I’m amazed to hear that Kevlar armour is (or at least, was) standard protective equipment in some mines.

Common practice in longwall mining is to dig out all the coal in a seam, leaving the unsupported mine roof to collapse eventually into the void. Under some geological conditions, acres of mined-out roof can stay up without support. When a section of roof suddenly collapses, the result is an air blast that can throw a miner off their feet. Or worse.

Bill himself once spent 26 weeks in Newcastle hospital after a rock fall. The man next to him was crushed to death. “We lost nine in that mine”, Bill recounts.

We sit for an hour, maybe more. Bill talks about working life, and death, in the mines.

Asked about climate change, and what that means for the coal industry, Bill is direct: “It’s all got to change”, he tells me. “We have to save the planet.” He’s seen the climate changing himself. He’s checked out documentaries about gas fracking in the US, and tells me about a recent Four Corners doco on the subject. The idea that we need to transition away from fossil fuels quickly doesn’t seem at all controversial.

In all of Bill’s stories there’s a deep and obvious pride in the union. But there’s no love for the coal industry as such. Maybe it’s hard to romanticise an industry that has killed so many of your workmates. He’s scathing about the open-cut mines. “That’s just pillaging the countryside, really ... Go to the upper Hunter, Jerome, and have a look at the open cuts. Every kid’s got asthma from the dust.”

An open cut coal mine in the Hunter Valley PHOTO: Kate Ausburn (Flickr)

The union in Bill’s stories is an organisation that is, of course, centred on the workplace – but it reached deep into the communities where the coal miners live.

As the president of the union lodge, after any fatality it was Bill’s job to visit the home of the miner, to break the news to the family. “You didn’t have to say anything. They’d see you walking up the path to the house and they’d know what’s happened.” Bill tells of one such visit: the wife of the killed miner screaming, smashing every bit of crockery and glass in the house, walking over it in bare feet, still screaming, while Bill phoned for a doctor.

He tells the story of a miner’s young son who, for four months after his father’s death, hadn’t spoken a single word. The union organised for the son, a keen fan of the Canterbury Bulldogs rugby league team, to travel to Sydney to spend a day with a champion Bulldogs player and his family, and to see a game. At the end of the day, when asked to thank the family, the son broke his silence for the first time since his father’s death.

“When I started”, Bill explains, “our slogan was: touch one, touch 14,400. That was how many members the Miners’ Federation had in the Hunter”. Bill tells hilarious stories of the time 8,000 miners gathered in Newcastle to boo right-wing Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen back into his limousine, one of a series of mobilisations that helped to derail the “Joh for PM” push. He recounts incredible scenes of thousands of miners converging on a new open-cut mine in the upper Hunter to chase half a dozen scabs out.

A couple of times, I bring Bill back to the issue of climate change. Each time, he gives me a short, direct answer—and then shifts the topic. Or at least, he seems to.

I raise the issue of “a just transition”, meaning that workers have to be given justice in any transition to a new, non-carbon economy. He replies simply: “Oh yes, of course, everyone has to be looked after”. And then tells me the story of a workmate who, as soon as he started work in a mine, took out a bigger mortgage and bought a new car. “‘Be careful’, I told him. ‘Don’t count on that money: there might be a strike, you might get nothing next week.’” Bill continues: “And sure enough, there was a strike—and guess who had to sell his house”.

This sort of exchange happens a couple of times. It takes a while for me to work it out. Bill isn’t straying off the topic; he’s just taking me around the long way. He’s telling me that there’s more to being a working-class militant than the money. That there’s a higher purpose that organised workers at our best can pursue.

********

Our group has a retired teacher who is finding ways to gently challenge the climate change denying myths peddled by the prime minister and recycled by some of his fellow Rural Fire Service volunteers; a mine worker, surprised anyone would be surprised that most of his workmates have no issue with the science of climate change; and a retired miner who declares in a matter of fact way that “We have to save the planet” and that “It’s all got to change”. This group is probably not typical around here, Jason’s reaction to this idea notwithstanding. But on the other hand, people who see climate change as a major threat don’t seem super hard to find.

It strikes me that there would be a role for a political force that could take the views of people like Alan, Jason and Bill, and amplify them. Perhaps even organise them to engage with other workers and community members in the area to counteract the lies that abound on climate, and to open up a discussion on what a coal-free future could or should look like. Perhaps this force could organise to win new jobs at least the equal of what coal once was. It could certainly use the powerful voice that coal industry workers have as part of a national debate, advocating for the sort of rapid, dramatic action that is needed.

Ideally, this political force would be embedded in the local community. It would have credibility through having steadfastly advanced the interests of workers in their battles with the giant companies that dominate the coal industry. It could pursue both the immediate interests of coal and power industry workers while also pursuing their longer-term interests, and those of the vast majority of humanity, including the need for a liveable planet. It would bring the extraordinary industrial power of coal workers to bear to win compensation and ongoing jobs for the entire community. Being an organisation of workers, it could reach into every workplace and community to have these debates out, repeatedly, as it planned a path forward.

The workers of the Hunter Valley have no such organisation. Instead, they have Joel Fitzgibbon.

The local Labor Party, like ALP branches across the country, is a hollowed-out shell. Fitzgibbon was first preselected for the seat of Hunter a quarter of a century ago by a local branch of 80 people. The electorate at that time had 85,000 voters.

“Oh he’s getting out and about a bit more since the last election”, is one view of the sitting member: “At least he’s better than his dad” is another. Joel Fitzgibbon inherited the seat of Hunter from his father, Eric Fitzgibbon, who seems to have been even more notorious for turning up to union events only around election time.

This seems par for the course. I’m told of a union meeting at which one former MP was so drunk that a group of miners decided to remove him from the meeting, dumping him in a bobcat and tipping him out outside the mine site. Labor doesn’t seem to believe that it owes better representation than this to some of the best-organised workers—and the most solid Labor voters—in the country.

The reasons for this hollowing out are no mystery. Eric Fitzgibbon’s dozen years in parliament from 1984 coincided with the Hawke/ Keating Labor government, which succeeded in suppressing industrial action, restructuring industry and boosting the share of economic output going to profits. A party alive with debate is not an asset to achieving this aim, and the local branches accelerated their decline.

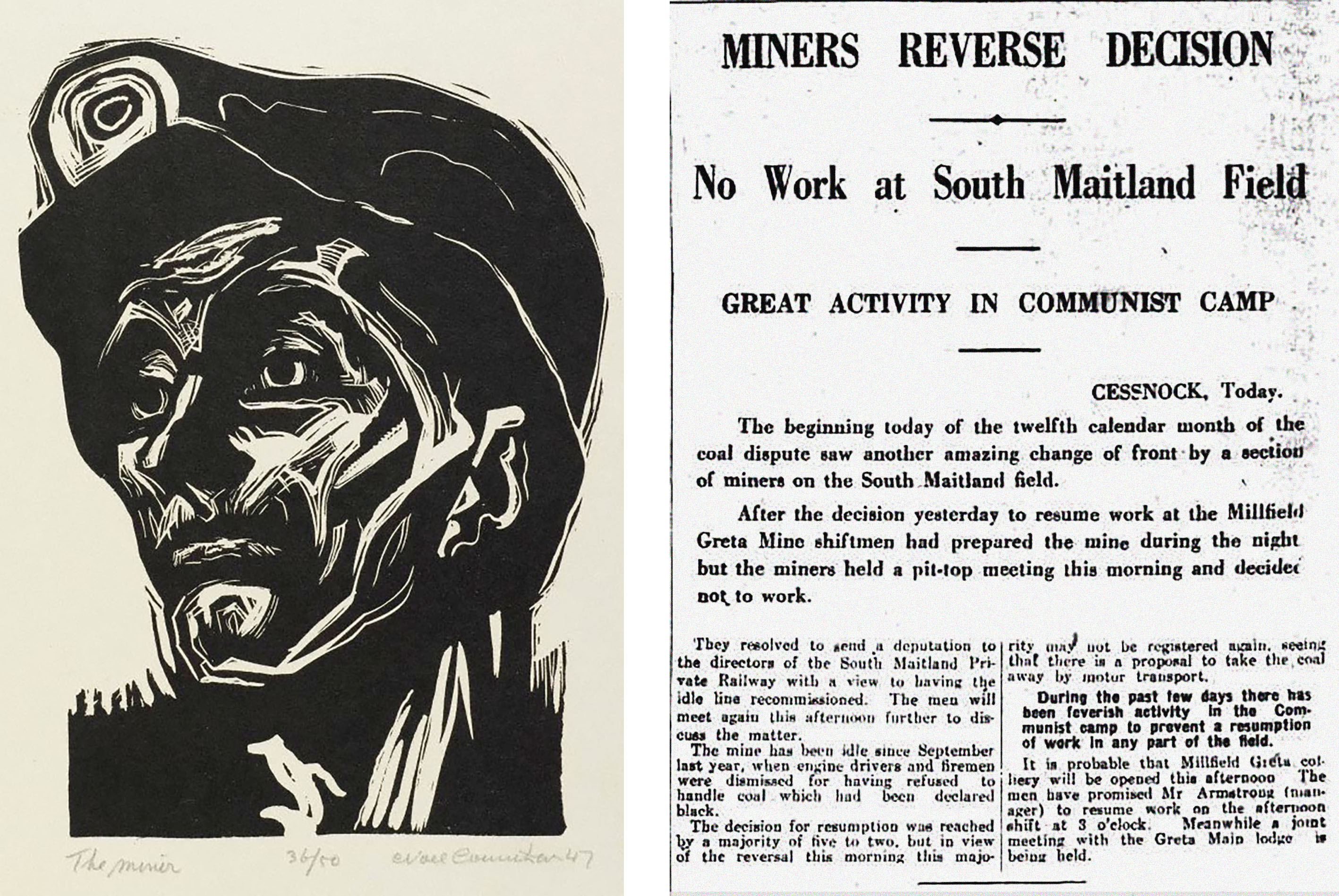

In previous generations, there had been vigorous challenges to Labor’s political monopoly among workers in the Hunter region. The Communist Party, famously, once had a majority on Cessnock’s local council. But no such forces exist today.

The decline of Labor, the absence of political alternatives, and the slow retreat of union power has left a significant political vacuum in Hunter and the surrounding areas. Into that void has roared One Nation.

Most commentary assumes One Nation’s extraordinary 22 percent 2019 vote in Hunter was a revolt against Labor’s climate policies. That has certainly been Joel Fitzgibbon’s line. The conclusion we’re meant to draw is that the One Nation vote proves that Labor’s far-from-ambitious climate targets will never be embraced by blue-collar workers and must be abandoned.

One Nation’s vote in the Hunter does seem to be based, in large part, on blue-collar workers who would usually vote Labor. Labor’s primary vote plunged by 17 percent, while the Nationals’ declined by only 3 percent. The biggest polling booths in the electorate, the pre-poll booths in the mining centres of Singleton and Muswellbrook, show votes for One Nation of 25 percent and 28 percent.

Saying that all of this swing is to do with climate policy, however, leaves out a crucial part of the story. In the Hunter region, One Nation also made a very vigorous contest, not just on climate issues, but on the key issue of casual employment.

It was Labor in the early 1990s, the government Eric Fitzgibbon was part of, that broke up industry awards and made enterprise bargaining compulsory. This was the first step towards today’s situation, in which a huge proportion of the workforce—around 60 percent in BHP’s coal mines—is employed through labour hire companies.

Labour hire workers have a lower hourly rate than directly hired, ongoing coal workers. And they don’t get productivity bonuses, leaving them 30 to 40 percent worse off. Casual workers in fear of dismissal are also reluctant to speak up on health and safety issues: a recent survey of 1,000 coalminers in Queensland found 90 percent agreeing that “Casualisation of jobs at my work site affects safety”.

One high profile example of the horrific human cost of casualisation is the case of Simon Turner, who came to prominence in early 2016 in a series of articles by the Newcastle Herald’s industrial reporter Ian Kirkwood.

Turner suffered a catastrophic injury in late 2015, while working as a driver for labour hire company Chandler Macleod at the giant Mount Arthur open-cut coal mine, owned by BHP. Turner was instructed to keep working on a day when visibility was close to zero due to extreme dust. His truck was struck by an excavator and Turner was thrown across the cabin. Despite suffering serious pain, Turner was told by management to return to work without reporting the injury, to keep down “lost time injury” numbers. Neither Chandler Macleod nor BHP reported the incident to the authorities.

Turner is now classified as TPD—“total and permanent disability”—with a back injury and a left leg that collapses on him without warning. If Turner had been employed by BHP, he would have been covered by the compensation laws governing the coal industry. But because Chandler Macleod operates in many industries, the company wasn’t classified as a “coal mining employer”. So Turner has to survive on $400 per week from the inferior state-based workers compensation scheme, while dealing with crippling, lifelong injuries.

Workers being chewed up and spat out by giant mining companies is sickening, but it’s hardly new in the coal industry. What gave Simon Turner’s story a much wider significance is the legal challenge he launched in 2018 with employment law firm Adero, claiming that his employment as a casual was unlawful.

The Adero claim went much further than recent CFMMEU court cases in which the union fought for annual leave and sick pay for “casuals” employed on a regular roster. If successful, Turner’s case would result in a total ban on casual employment in the black coal industry.

This is because the Black Coal Award is the only award in the country that bans casual labour, prohibiting it for mine workers. This important provision was won by the union on the basis that the special hazards of coal mining mean that a regular work group is essential—not a revolving door of workers unfamiliar with each other and the industry.

Adero’s argument is that because of this award condition, every single enterprise agreement which allows for casual labour in the coal industry, anywhere in Australia, must fail the “better off overall test”—the legal minimum for the Fair Work Commission to approve an enterprise agreement.

To put it mildly, this is dynamite. If successful, the case would rewrite employment contracts in the coal industry nationwide. And it would also raise the question: why has the union itself not pursued this issue, and why has Labor kept it at arm’s length?

Kirkwood has reported that, during a dispute with Chandler Macleod in early 2015, the CFMEU (as it then was) issued a letter to labour hire workers at Mount Arthur stating:

“We have brought to Chandler Macleod’s attention that there is no casual production classification in the award. The casual classifications are only for staff positions.

“Don’t be fooled into thinking that the agreement ... is for your protection, in fact it is to aid them to get around providing terms and conditions that should be afforded to you under the award.”

However, the union then settled with Chandler Macleod for an enterprise agreement with a $3 per hour increase—which still left workers employed as casuals tens of thousands of dollars behind the directly hired workers.

There can be a vicious circle when a union with little industrial strength uses award conditions as a bargaining chip, rather than a minimum to be rigorously enforced—or at least publicly and vigorously campaigned over. This leaves the union in a situation in which it is seen playing catch-up at best. Turner quit the union early in his employment at Mount Arthur because of its lack of action on casuals.

Turner’s legal case hasn’t been won, or even properly heard yet. It was bogged down in technical issues over funding for a year, and faces an uncertain future due to the Morrison government’s regressive changes to laws governing casual employment in early 2021. In the meantime though, the political issues the case raises have been broadcast through the area via Kirkwood’s reporting in the Newcastle Herald, syndicated to local publications in mining centres such as Singleton and Muswellbrook— and picked up and amplified by One Nation.

When Kirkwood first brought Turner’s case to prominence in 2016, Turner’s main political advocate was NSW Greens MP David Shoebridge. By 2019 though, easily the most prominent public advocate for this case was One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts. Roberts invited Turner to give evidence at Senate committees in Canberra, talked up the case in parliament and made sympathetic videos.

Fitzgibbon has done none of these things. His response to Roberts’ allegations was: “Now while some might be open to the idea that a coal company might be interested in prioritising profit over people—not something I subscribe to—surely no-one would believe that the union is capable of such thinking”.

Roberts comes across as much more combative, attacking “BHP, the Big Australian, who disregards and discards everyday Australians and leaves them underpaid, broken, abandoned ... The CFMMEU ignored the rights of these honest workers from beginning to end. They signed off on a sub-standard employment agreement. The CFMMEU broke the trust of these workers and discarded them. When these workers took their concerns to the local federal Labor member of parliament, Joel Fitzgibbon, they were shown the door again, six times. As did the ALP state MP and Liberal state ministers”.

The fact that local One Nation candidate Stuart Bonds is a CFMMEU member and works in the coal industry adds to the party’s credibility in Hunter.

“A union is a union and coal companies are coal companies”, Bonds says in one of Kirkwood’s reports. “Put them together around the table in the way they are here and there’s been no incentive for anyone to blow the whistle on anything, and that’s what’s happened.”

So in Hunter at least, the big One Nation vote is partly a revolt against Labor on bread and butter economic issues, not simply on climate policy. This is important, because it means that no amount of talk about a “just transition” from coal is going to fill the gap between One Nation’s combative rhetoric and Fitzgibbon’s fanciful declaration that big companies like BHP don’t prioritise profit over people.

It’s important to note that One Nation’s rhetoric as champions of workers’ rights is utter bullshit. Malcolm Roberts’ parliamentary speeches show a profound objection to one of the most basic aims of unionism: establishing a common rate for the industry, to take wages and conditions out of competition. Roberts declared in 2016: “This so-called level playing field is at its core price fixing”.

So it’s no surprise that Roberts hailed 2016 legislation targeting the construction unions as a contribution to “total human freedom”, which cracked down on the “cartel behaviour” of “CFMEU thugs”, who were “wreaking havoc” and “castrating our economy”. Roberts “proudly” spoke at the HR Nicholls Society, which has been proudly helping to bust unions since the 1980s.

One Nation’s biggest contribution to the business elite at the expense of workers has been to help rehabilitate racism and bigotry as a weapon in Australian political life. Pauline Hanson accused Asian migrants of failing to assimilate, and Aboriginal people of cannibalism. Whipping up rage and frustration at these targets is a huge gift to the business elite, because it distracts and divides ordinary people, rather than focusing anger on the big businesses that profit from insecure work and a threadbare social safety net.

Over the years, One Nation has shifted its rhetoric. Raging against Muslims is more fashionable than attacking Asians nowadays. And it’s added another string to its bow: climate change denial.

“Climate change is a scam”, Malcolm Roberts declared in his first speech in parliament. There is “no empirical evidence that the production of human carbon dioxide is affecting the climate and needs to be cut”, he argues, so “All climate policies need to be scrapped”.

The evidence of our own senses, of meteorologists and of several thousand climate scientists tells us otherwise.

There’s no doubt that climate change denial is a big part of One Nation’s appeal. Given the constant denial or downplaying of climate change by the conservative press and government, it’d be amazing if things were otherwise.

It’s not enough just to dismiss this blizzard of bullshit: we need an army of people equipped with arguments to counter it. One model is the movement against uranium mining back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Activists took education and argument seriously, organising to speak with unionists at workplaces and in working-class communities to advocate their position and debate the issues.

This is worth doing. But it’s not sufficient—because there’s another logic at work here.

When I checked in with my interviewees before publication, Jason included this point in his reply:

“My recent thoughts are around the challenges we will leave the next generation. In my youth, you could leave school at 16 and get a well paid job, the union could fight for my work conditions and pay, my first house cost less than one year’s salary. Alan, Bill and myself have benefitted from the golden economic times in this valley. The young guys with big mortgages are the ones under pressure and will be most affected by the decline of coal. With this in mind I am really reluctant to judge those who are unwilling to embrace the science.”

It’s an important point, in a few different ways. With economic insecurity a permanent fact of working-class life, there’s a powerful incentive to rationalise away any threat to the scraps of economic security a worker still has. So, countering the lies on climate change would be a whole lot easier if there was a fight going on at the same time that addressed that economic insecurity—for instance, on casual work.

Labor’s track record in office is another significant obstacle. Labor can’t say they’ll retrain and re-employ everyone from the coal industry in the state-owned electricity industry as we retool for a carbon-free future, because the industry has been sold off—by Labor in Queensland, Labor and Liberal in NSW and the Liberals in Victoria.

This is a practical problem, and also a political one. Anyone in their late 20s or older has experienced Labor in government, promising much and delivering little.

So, given a choice between vague platitudes of a “just transition” from a distrusted Labor and a full-throated rejection of the need to shut down coal, combined with a vigorous defence of coal miners against casual labour, it’s no surprise that 22 percent of voters in Hunter went for One Nation.

There’s a final difficulty: the low ebb of union struggle. The experience of workers going on strike and forcing the bosses to do something that they didn’t want to do is a crucial foundation for any sort of working-class progressive politics. That actual experience teaches workers that we can change the world in a way that is simply impossible from reading books.

In the 1970s, a high rate of industrial action underpinned important movements to save the planet and people in Australia. Pamphlets about a “just transition” are not an adequate substitute.

I have plenty of time to think about all this on the long drive back to Melbourne. I write up my discussions in early March. But in the days and weeks that follow, as the pandemic intensifies, my job as industrial organiser for Socialist Alternative goes from its normal busy routine to all-consuming.

A few times, I pick up the threads of this article. The main themes are clear enough. The myth of regional communities, rock-solid in their agreement about coal and the carbon economy, is just a myth. In fact, there’s a pretty vigorous debate in these areas. One side in that debate seems to be aided and abetted by every climate-denying politician and media outlet in the country, but the other side is lacking organisation and political confidence. Labor’s problems in the regions are at least as much to do with their weaknesses in office as their promises on climate. It’s all this that leaves Labor open to a serious challenge from One Nation.

The problems are clear enough, but the solution isn’t coming to hand. In order to try again to find it I’ve got to go back to the start of my journey, in the Victoria’s Latrobe Valley.

‘No-one got left behind’: the Latrobe Valley

Ask former power station operator Ron Ipsen about the phrase “just transition”, and you’ll get a laugh. Not the sort of laugh Ron gives when something tickles his sense of humour, which happens often enough as we sit drinking tea in his good-sized shed, crammed with machinery of all sorts, outside the town of Moe in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley.

Mention “just transition” to Ron, and you’ll get a pointed, bitter laugh—the sort that indicates that bullshit is being called. This surprises me. After all, on several accounts, Ron is the person responsible for introducing the phrase to Australia.

Ron Ipsen’s shed was an early stop on my visit to three of Australia’s main coal districts last year to discuss coal and climate, workers and politics—and this elusive concept of a “just transition”.

The smoke had only just cleared from the catastrophic bushfire season of 2019-20. An incredible 7 percent of the vast land mass of New South Wales had just been incinerated. Thirty-four people were dead from the fires. Another 400 were dead from the smoke, and probably another 4,000 had been admitted to hospital, with an unknown number (including newborns) suffering ongoing health problems.

This, it seems, is the new normal. If we’re lucky. The phenomenal heat of 2019—the hottest year on record in Australia—will be typical in a world that is 1.5 degrees warmer, according to the Bureau of Meteorology and the CSIRO. And on our current disastrous settings we’re headed for much, much more than 1.5 degrees of warming.

As well as the bushfires and the approach of further catastrophe, the results of the May 2019 federal election cast a long shadow. Significant swings against Labor in some coal districts led to a chorus of media and political pundits declaring that the main blockage to effective climate action in Australia was the unshakeable commitment to coal on the part of working-class communities in regional areas.

Of course, anyone who actually goes to these communities will find something quite different from this stereotype. There’s a vigorous discussion, and sometimes a sharp argument, about coal, climate and the energy “transition”.

In Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, it’s easy to find an acute awareness of the declining returns, and heavy costs, of the fossil fuel economy.

The brown coal-fired power stations of the Latrobe Valley generate two-thirds of Victoria’s electricity, down from 90 percent a little over a decade ago. The benefits flowing from Victoria’s power industry to Latrobe Valley workers and communities have been in steep decline since privatisation in the 1990s, however.

And the heavy—and sometimes horrific—cost of coal was dramatically demonstrated in February 2014. On a searing hot day, following a record-breaking heat wave, a fire took hold in the Hazelwood open cut coal mine. The sprinklers and water pipes which had, years earlier, kept disused parts of the mine safe from fire, had been ripped up and sold for scrap by the new owners after privatisation.

So, for 45 days in February and March of 2014, a plume of poisonous smoke billowed uncontrollably from a massive, burning section of the vast Hazelwood open cut mine into the town of Morwell and the wider Latrobe Valley.

Ron Ipsen and Wendy Farmer were part of a team of locals who scrambled to respond. They demanded relocation assistance for all who needed it, as well as immediate medical check-ups, and regular health check-ups to follow.

They called a rally in Morwell. More than a thousand people turned up. And they counted the dead.

With Births Deaths and Marriages refusing to release the figures, Ron and Wendy formed a team that combed through the death notices in the local papers and found a spike in deaths of 30 to 40 percent in nearby towns.

The activists founded Voices of the Valley, signed up hundreds of members, and campaigned successfully for the incoming Victorian Labor government to reopen an inquiry into the mine fire and its health effects after the 2014 election. A long-term health study was commissioned as a result of their campaigning, which found a decrease in lung function equivalent to ten years of ageing among residents exposed to mine fire smoke. Children exposed to the smoke during their mother’s pregnancy were found to exhibit more respiratory symptoms. The Hazelwood health study is the only one in Australia to measure the health effects of major smoke exposures; it proved a grim and useful benchmark for studies after the 2019-20 bushfires.

Over time, Voices of the Valley shifted their focus to the economic effects of the looming closure of coal-fired power stations in the Latrobe Valley. They’ve won around $400 million channelled into local projects through the Latrobe Valley Authority over the past few years. An enormous number of community projects have been funded—refurbishing local halls, rebuilding sporting facilities and promoting community engagement.

Not all the projects associated with an energy transition have been executed well, or at all. Ron is frustrated that, despite his best efforts, there was no move by government to get a solar panel factory built in the valley. But despite these problems, both Ron and Wendy give points to the Latrobe Valley Authority for listening, adapting and funding a string of projects.

Wendy’s husband Brett worked in the Hazelwood open cut for years, operating the colossal dredging machinery that ploughed up the brown coal to supply the power station. It’s a skilled and specialised job. But when Hazelwood shut with just a few months’ notice in 2017, Brett and his workmates didn’t have tickets that would allow them to apply for other work. So retraining organised by the authority was useful, along with a scheme in which 90 Hazelwood workers replaced workers who took early retirement at nearby stations.

This brings us back to Ron Ipsen in his good-sized shed outside of Moe—and his reluctance to embrace the term “just transition” to describe these achievements.

Ron is happy enough to talk about his role in popularising the “transition” part of the phrase. A few years back, he had an encounter with Greens activists campaigning to shut Hazelwood. At that time, Hazelwood was the most polluting power station in the country. “Don’t come into our community saying shut things down”, he told them. “All you’ll do is get people’s backs up.”

“Coal-powered stations are like dinosaurs”, Ron tells me. “They are incredible pieces of machinery, but the economics is killing them. You don’t have to hang banners or protest out the front for them to die out. What you do have to do is help the community move forward in that transition. Talk about what we can transition to.” Within a few days of this exchange, the Greens shifted their emphasis from “shutting Hazelwood” to instead talking about a “transition to” a new grid.

But adding the word “just” to the idea of a “transition” doesn’t strengthen the phrase, in Ron’s view. In fact, the opposite.

Ron recounts hearing a local union leader and political candidate state that, because power station operators can earn a wage of $140,000 per year, a “just transition” consists of each of these workers transitioning to an equivalent job, on the same rate of pay, for the rest of their lives. Ron, a former power station operator himself, isn’t impressed.

I tell Ron that I don’t really understand his objection.

For most of the past century, every cent of wealth that has flowed through Melbourne’s financial heart of Collins Street has depended on the work of people in the Latrobe Valley, digging the coal and working the power stations. It seems to me that if some of those workers are on good money, then that’s good—and it’s entirely reasonable for them to insist they should stay on the same wage. Not only that, but power station operators have surely got the industrial power to win a guarantee of something like that, on this side of the “transition” anyway.

None of this impresses Ron. But rather than directly contradicting me, he gives me a stern look and takes me around the long way.

Before privatisation in the 1990s, Ron explains, Victoria’s State Electricity Commission (SEC) was an enormous industrial enterprise. The SEC employed 12,000 people at its height. There were not only power station operators who had risen through the ranks like Ron but maintenance crews, a dedicated firefighting force, massive workshops including foundries, and plenty more.

“The thing with the SEC was, no-one got left behind”, Ron says. “Not everyone has a trade. Not everyone is going to be a power station operator. But every light bulb in that power station has to be changed. So someone had the job of doing that—replacing every light bulb. Someone had the job of cleaning.” These workers were often well paid, with many coming in at the top 5 percent of blue-collar wages.

An incredible 9,000 workers were thrown onto the scrapheap as a result of privatisation in the 1990s. Most of the workers in the workshops and maintenance crews were promised jobs that never materialised, explains Ron. Or if they did, it was on much lower rates of pay, with outsourced contracting companies. Most of the less skilled jobs were simply abolished. No-one, Ron points out, is talking about a “just transition” for any of these workers, decades after the event.

This sickening wave of sackings left the power station operators and a few other highly specialised roles, the section of the workforce that is hardest to replace, as the only people still directly employed by the new, privately owned, power-generating companies. It’s the idea of advocating for this limited section of the workforce, and calling this a “just transition”, that produces Ron’s scornful laugh. Wendy Farmer puts essentially the same idea to me: “A just transition is about more than someone on $140,000 staying on $140,000. A just transition is about the community moving forward”.

Shaking $400 million out of a government for a community in transition is no small feat. Wendy points out that unemployment actually fell in the Latrobe local government area, from 11.1 percent to 7.1 percent, in the three years following the closure of Hazelwood power station in 2017.

This level of community organisation and government engagement is the best current example anyone in Australia can point to of what a successful “transition”, or even a “just” transition, might look like. There’s been interest from around the country and around the world.

These achievements have their limitations though.

Wendy’s daughter, Naomi, gives a perspective as a long-time socialist activist, who grew up in the Latrobe Valley and has lived there on and off since. Naomi uses the term “neoliberal money” to describe many of the projects, meaning “individual solutions for collective problems”.

Latrobe Valley residents, Naomi tells me, die five years earlier than other Victorians. It’s difficult and expensive to do a lot about the main factors behind this— emissions from power stations, concrete works, the pulp mill—as well as the poverty and grinding stress that have been part of the valley’s lot in the decades following privatisation.

Naomi points out that subsidising triathlon courses or organising sunflower planting to attract native birds and beautify the place is a whole lot easier than tackling these chronic issues. Naomi completed the triathlon training. She appreciates the sunflowers and the native birds they bring. She’s obviously proud of the role her family and the other activists of Voices of the Valley have played, but she wants the limitations recognised as well.

Politically, there’s certainly a strong nostalgia for the secure, well-paid jobs of the past, which can translate to a political attachment to coal. Ron chuckles as he recounts how his cousin stopped speaking to him for 18 months after Ron started advocating for a solar panel factory in the Latrobe Valley. But electorally, the situation in the Latrobe Valley seems a world away from the picture in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales, where One Nation got more than 20 percent of the vote in 2019 and nearly cost Labor MP Joel Fitzgibbon his seat.

The Latrobe Valley is split between two largely rural federal seats, both of which are safe for the Coalition. But unlike in the Hunter, both seats saw small swings to Labor in 2019. The grab bag of right-wing independents and parties, including One Nation and Clive Palmer’s party, failed to increase their votes significantly from 2016.

So the electoral figures for the Latrobe Valley don’t support the lazy right-wing talking points about coal communities everywhere embracing reactionary parties due to disenchantment over Labor climate policies.

Overall, a visitor to the Latrobe Valley is left with plenty to think about. Amidst all the verbiage about a “just” transition, I’d never really put it together, until Ron pointed it out, that the vast majority of the workers from the power industry had already had a brutal and very unjust “transition” imposed on them, decades ago.

The money won by Voices of the Valley campaigning—$400 million over five years—has done a lot of good. It’s also a figure totally dwarfed by the (largely tax-free) profits of the private operators of the region’s power stations. Earnings before interest and tax have been estimated at around $400 million in 2018 alone for each of Yallourn and Loy Yang B, and more like $700 million for the giant Loy Yang A power station.

Given the colossal amount of wealth that has flowed from the labour of generations of workers in the Latrobe Valley, and given the scale of the health and environmental impacts that will persist for generations to come, the word “just” seems out of place.

The profitability of all these power stations is under serious pressure. But still, I’m sceptical about Ron’s argument that coal-fuelled power stations are going the way of the dinosaurs. The dinosaurs, after all, didn’t have an army of political fixers and corporate ex-staffers making policy for the Australian and other governments, rewriting market rules in order to put off the day of reckoning.

So after 170 million years on the planet, the huge majority of dinosaurs, along with most other species, were wiped out in a few hours, it seems. Short of an asteroid hitting, nothing at all similar is going to happen to fossil fuels. Most coal-fired power stations have years to run, or even decades.

Not only that, but electricity is only one part of the equation. If we include transport and other energy use (for instance, gas burned for domestic cooking or industrial purposes), fossil fuels still make up 93 percent of Australia’s energy mix.

It’s not that we lack the technical ability to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Rather, it’s that our economic and political systems are stopping the solutions being applied rapidly, at the massive scale we need. It’s this which means that, barring an extraordinary event, we’re in the early stages of a hothouse Earth.

This becomes even clearer after a day and a half of driving, from the Latrobe Valley to Mallacoota and then up the south coast of New South Wales, through landscapes dominated by charred and leafless forests, stretching as far as the eye can see.

The problem of steel: Port Kembla

“The higher you go, the less interest there is.” It’s early 2020, and I’m talking with a white-collar worker at Australia’s biggest steel mill, operated by BlueScope at Port Kembla in Wollongong. We’re discussing the remarkable lack of interest in climate change among various layers of management, at a site which produces 1 percent of the annual greenhouse gas emissions of the entire country.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the main greenhouse gas causing the heating of Earth. The last time there was this much CO2 in the atmosphere, our ancestors still hadn’t come down from the trees and the site of the Port Kembla steelworks, along with most of the rest of the city of Wollongong, was under water. As were most other coastal cities on Earth.

But for now, the Port Kembla steelworks is still above the waterline, and pouring out the CO2. Every year, the blast furnace at Port Kembla sucks in 3 million tonnes of coal along with 5 million tonnes of iron ore and various other industrial inputs. The result is around 3 million tonnes of steel—and close to double that amount of CO2. The steel industry produces 8 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a massive problem for all of us.

The Port Kembla steelworks PHOTO: Jamie Caulfield

So it’s startling to learn that the limit of management ambition at this key industrial facility is a reduction in “carbon intensity” of around 1 percent per year. This is just a fraction of the 8 percent annual reduction in greenhouse gases which would be needed as a minimum, worldwide, to cut greenhouse emissions by half in the current decade. If the world as a whole subscribes to the same level of “ambition” as management at BlueScope Port Kembla, we’re headed for hell on Earth.

The particular worker I’m talking with doesn’t want to be named, so we’ll call him Donald. He’s involved in the local climate movement, and he’s one of around 3,000 employees and 2,000 contractors—blue collar and white collar—whose labour keeps the Port Kembla steelworks operating.

Donald has thought about possible accusations of hypocrisy that could be directed at a climate activist who earns their living at the steelworks, and rejected them. If we’re going to win on climate, we’ll win because of the movements we build and the social changes we collectively make, not because individual workers drift out of the steel industry—or the construction industry (7 percent of global emissions), or electricity (31 percent), or agriculture (11 percent), or transport (15 percent), or any of the world’s productive systems—all of which need rapid and far-reaching transitions within the next decade if we are to limit global warming.

Technically, the path to coal-free steel-making seems strangely straightforward. Donald explains that the blast furnace is the first and most CO2-intensive step in manufacturing steel. Coal and iron ore—basically carbon and iron oxide—are heated to around 2,000 degrees in the blast furnace. The carbon in the coal draws off the oxygen in the iron oxide. The result is crude iron (usually called “pig iron”) for further processing, and around double that amount of CO2 as a waste gas.

The effect of replacing carbon with hydrogen in the blast furnace is to change the main by-product from CO2 to H2O (water). Donald explains that existing blast furnaces don’t have to be rebuilt in order for this process to work: in late 2019, German steel corporation Thyssenkrupp successfully injected hydrogen, instead of coal, into an operating blast furnace.

Of course, there’s a huge and expensive infrastructure of hydrogen production and transport which would have to stand behind a large-scale substitution of green hydrogen for coal in steel-making. With current technology, less than a quarter of the coal in a blast furnace could be replaced by hydrogen. A steel-making method known as “direct reduction” that can support zero carbon production would require a major rebuild of existing facilities. There are a bunch of technical challenges to do with the iron content of the iron ore, and handling hydrogen. But it’s doable, with enough financial backing and political will.

The thing that frustrated Donald the most about management at the steelworks in early 2020 was their complete lack of curiosity, let alone practical interest, in green steel-making. Donald interacts with management at various levels. Whenever climate change comes up as a topic, it’s shut down almost immediately, he tells me. “‘It’s not my area’, is one common response, or ‘I don’t have time’, or ‘Are we even going to be here in ten years?’ The higher you go, the less interest there is.”

No-one would have this impression from BlueScope’s corporate sustainability report, which trumpets “the integral role of climate action for our business, incorporating climate change as a key pillar in our revised corporate strategy—a defining signal of our commitment to action ...” And so on.

But BlueScope’s “key pillars”, “integral roles” and “defining signals” start to look a lot less grand as soon as we leave the hypothetical, hyperventilating world of corporate social-responsibility-speak, and enter the real world in which CO2 is emitted and profits have to be made. “A significant challenge for BlueScope is matching the desire to decarbonise operations with the need to remain competitive”, notes the company’s sustainability report.

And here we have the heart of the problem.

Every steel producer—and every government—draws the same conclusion as BlueScope management: the “desire to decarbonise operations” has to take second place to “the need to remain competitive”. We live in a global, dog-eat-dog system of competing corporations and states. The pace of change is dictated by the limits of profitability. What humanity and the planet require simply doesn’t feature in that calculation.

Management might be limited in what they can do to limit climate change, but there are no such limits on expressing good intentions. An ocean of corporate spin is the result. In 2017, BlueScope was one of the corporate co-founders of ResponsibleSteel™. ResponsibleSteel™ exists to formulate a definition of “sustainability”, and then certify its corporate founders as “sustainable”. Unsurprisingly, BlueScope is set to achieve “sustainable” status from ResponsibleSteel™ sometime in 2021. If you can’t be good, the old saying goes, you can at least try to look good.

Unsurprisingly, management take a dim view of their employees speaking out publicly to demand real action on climate. One worker mentions an informal warning from management after being seen at a climate protest. Workers in carbon-intensive industries can have a powerful voice in any discussion on climate change. BlueScope’s management doesn’t want its workers using that voice to challenge the carbon economy—or anything else, for that matter.

In 2015, management forced every worker to sign a code of silence, while the company took advantage of a crisis to cut 500 jobs and impose a three-year wage freeze. “They made us sign to say if anything comes out, instant dismissal”, one worker told Red Flag at the time.

Helen is another worker in the steelworks. She remarks on the lively discussions among her work group on climate and every other topic, with every shade of politics represented from left-wing to far-right. Everyone has an opinion, and no-one is shy about sharing it. But all of them know to change the topic from anything controversial, including climate change, when management come around.

Work is a dictatorship. The most widespread repression of free speech in the country is employers silencing their workers, and BlueScope is no exception.

In the past, unionised workers at Port Kembla have exercised free speech collectively, and backed their views with real industrial power. A working-class movement infused with radical politics agitated and struck against militarism in the 1930s, famously banning shipments of pig iron to Japan, where it would be used to make munitions for a brutal war against China. Unionists used their industrial power to back the campaign for Aboriginal rights in the 1960s, and struck for public education in the 1970s.

Remarkably, this tradition of political activism backed by industrial power even extended to the economic foundation of the region—the coal industry itself. In 1970, a community campaign sprang up against a new coal loader being developed by Clutha Development Corporation at Coalcliff, north of Wollongong. Opponents of the mine included industrial workers who knew all too well the toxic hazards of working in coal dust.

Prominent local leaders of the main construction workers' union called on workers to ban construction on the facility. Despite strong backing from the NSW government of the time, an effective community campaign backed by the threat of union action led to the planned coal loader being quietly scrapped.

But at the Port Kembla steelworks today, there’s a problem.

“The union is useless”, remarks Helen. Her tone is matter of fact. There’s no sense of shock or outrage, no sign of a realistic expectation that the union could be better.

Helen, and probably everyone else in the steelworks, knows stories about the old days when workers would strike for days to reverse an unjust sacking. But they are stories, not the living, breathing reality of working-class power at the point of production.

Coming up with a collective working-class response to climate change is pretty difficult if the workers, collectively or even individually, are banned from publicly debating what’s needed. And a union that has failed to build real industrial power in the workplace is not going to be effective at challenging this repression of free speech, or at contributing much to social movements to win real action on climate change.

In the coal mines dug into the Illawarra escarpment overlooking Wollongong, the union movement seems to have maintained more of a hold than in the steelworks. Every year, 12 million tonnes of coal—for the Port Kembla steelworks and for export—are dug out of the coal mines in the district by around 3,000 workers. Through more than a century of struggle, these workers built a union with a proud history of militancy and radical politics.

Coal mining was once marked by frequent local strikes organised at pit-top meetings, with regional or national strikes to win conditions across the whole industry. But it’s been decades since the last national stoppage. And in every part of the industry, miners’ wages and conditions are under enormous pressure from contractors.

Martin, who doesn’t want me to use his real name, has worked underground in the coal mines around Wollongong for his entire working life. He’s positive about coal miners having an ongoing dialogue with climate activists. He very generously gives me a lot of his time on my last day in Wollongong.

The picture he paints is of a union under siege.

Martin outlines the significant disputes over contracting. There has been some success for the workers at the Peabody mine in Helensburgh and South32’s Dendrobium mine. However, at Appin West, hundreds of contractors are earning $400 per week less than the permanent workforce. The hourly rate is $4 per hour less, and much of the wage of the permanents is from production bonuses, which don’t apply to the workers employed by contractors.

Martin’s generosity with his time doesn’t imply agreement with environmental or climate campaigners’ talking points. He’s not impressed with arguments about subsidence and water, which are the basis for a campaign against the expansion of the Dendrobium mine underneath the main catchment for Sydney’s drinking water. Martin’s sentiments match those on the union’s website, which features a steady trickle of articles in favour of coal mine extensions as well as on the many legal and industrial battles to maintain wages and conditions.

When it comes to coal and climate, Martin is matter of fact. The mines around Wollongong produce coking coal for steel. So long as there is a steel industry using coal (which could be a long time yet, given the lethargy among the corporations that dominate the steel industry globally) Martin’s view is that the coal may as well be mined here in the Illawarra.

I ask Martin if he’s heard of the concept of a “just transition”. He smiles: “You’re swearing at me now”. He explains his dislike of the phrase: “There’s nothing ‘just’ about going from a high wage job to a low wage, insecure job”. Coal mining jobs are still some of the best paid blue collar jobs in the Illawarra district. Many miners thrown out of work in a “transition” won’t be paid anything like the same money locally. Martin references the closure of Hazelwood power station in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley in 2017.

Martin’s scepticism about achieving well-paid jobs as part of a climate transition is understandable, given recent history. In 2009, the South Coast Labour Council (SCLC) produced a plan for Port Kembla and the rest of the Illawarra region to spearhead the production needed for a green economy. However, as SCLC secretary Arthur Rorris noted in 2019 in the aftermath of the climate strike, little action has been forthcoming: “This week marks 10 years since the release of the Green Jobs Illawarra Action Plan. The premier, council, Wollongong University, TAFE and unions all backed it. But nothing has happened. Our industrial capacity and the challenge of climate change are still there but the political will has disappeared, and with it the investment and policy backing needed to make the plan a reality”.

Radical politics and real industrial power, exercised at the point of production, have made history often enough in the Illawarra. Unions supporting a decent political position, but with no realistic threat of industrial action to back it, have nothing like the same effect.

Martin, Helen, Donald and 8,000 other Illawarra workers and contractors in the coal and steel industries are faced with the reality of the climate crisis. They choked on as much bushfire smoke as anyone else in the 2019 bushfires. They have a repressive management and pretty much zero free speech, on climate or many other issues. Their unions are under siege and suffering from many years of retreat, leaving the workers without a collective vehicle through which to act—on climate change or much else.

One thing workers in the Illawarra are not doing is following the simplistic media narrative of “blue collar workers desert Labor in climate backlash”. Wollongong is in the federal seat of Cunningham, which remained solid Labor territory in 2019, as did the neighbouring seats of Whitlam and Macarthur. Two neighbouring seats remained Liberal (Hume, which is mainly rural, and Craig Kelly’s seat of Hughes in southern Sydney), but without any major swing.

The problem is, the low ebb of the union movement leaves workers with no way to intervene collectively into the debate—let alone to shape the outcome of that debate by using their own considerable industrial power.

So it’s no surprise that Helen says the number one way her workmates act to address climate change is purely individual: installing rooftop solar panels.

An incredible 2.68 million houses in Australia have rooftop solar according to Clean Energy Regulator data, or more than one quarter. This is remarkable evidence of ordinary people wanting to do something about the climate, as well as saving money. But as a strategy, it can’t deliver anything like the scale of change we need.

According to one federal government estimate, the combined total of electricity generated by every single small scale solar system in Australia last year was 14,000 gigawatt hours. This is not far off what might be needed to produce enough green hydrogen to replace all of the coal used in the Port Kembla steel works, and produce 3 million tonnes of carbon-free steel.

This would be a remarkable achievement. But the Port Kembla steelworks produces just 1 percent of Australia’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. So while the vast extent of rooftop solar tells us something about the popularity of action on climate, we’re going to need a very different outlet for ordinary people’s decent sentiments if we’re actually going to change course.

Prospects for a ‘just transition’

The good news first.

We have the task of transforming every single productive system on Earth as fast as humanly possible. Fortunately, “as fast as humanly possible” is actually very fast indeed.

Climate activist and researcher Jonathan Neale draws on a wealth of material to argue that greenhouse gas emissions from all sources (energy, agriculture and industry) could be reduced by 87 percent worldwide within 15 years, using only currently existing technology. Neale deliberately excludes non-solutions such as gas (barely better than coal once leaks of methane are taken into account), biofuels (which use up land needed for carbon sinks and food) and so-called “carbon capture and storage” (a myth, propagated by the fossil fuel industry as cover for future developments, which has never worked at anything like the scale needed).

Retooling every one of our productive systems would be a huge project requiring millions of workers. Neale draws on years of research to argue that a workforce of around 8 million in the US, a million in the UK, a million in South Africa, for example, would be capable of achieving this transformation. That’s a huge number of workers – a few less than the total existing construction workforce in each country. But it’s not outside the bounds of imagination.

In technical terms, the transition is achievable. In human terms, it’s essential. There’s only one problem: the psychopaths are in charge.

Joel Bakan in his 2003 movie The Corporation compared the profit-maximising logic followed by corporations and their chief executives with a list of psychopathic indicators. These traits include ruthlessness, lack of empathy, inability to form lasting relationships and the reckless disregard of consequences.

Bakan argued that there is a close match. The characteristic mentality produced by the dominant form of economic organisation on planet Earth matches the standard definition of a psychopath. This observation has now become a commonplace. The business magazine Forbes reports that “corporate psychopaths” are “rushing to the executive suite”, while academic researchers study the phenomenon.

The point isn’t so much about individual CEOs. It’s that each company, each bloc of capital, must expand regardless of consequences, or risk being overtaken or overwhelmed by other capitals. Profits have to come first, regardless of the murderous consequences, even when those profits depend on fuelling the climate catastrophe.

We see this in the steel industry, and far beyond. Each bloc of capital—Europe, China, the US—is looking over its shoulders at its rivals. Each is unwilling to risk being put at a competitive disadvantage by committing to the rapid, gigantic and expensive transformation of all productive systems that we require.

We can put this another way: a wholesale overhaul of the forces of production—that is, the entire productive system—is desperately needed. But it’s being thwarted by the relations of production—that is, who owns the economy.

So where does this leave us?

A practical solution

Our demands most moderate are

We only want the Earth

– James Connolly, 1907

Removing the psychopaths from control of the extraordinary productive network that spans the globe would remove the single greatest obstacle to rapid, effective action to tackle the climate crisis. Take out the enormous power of capital, embedded in states and corporations, and we would be left with the technical, human job— enormous, but definitely achievable—of rapidly driving down emissions, retooling productive systems and dealing with the multiple planetary crises, environmental and social, that we face.

This would require the vast majority of humanity, who currently build and operate the world’s productive systems but who own none of them, to seize collective control.

This would not only be our best chance to limit the developing catastrophe; it would also be our best chance to survive it. A world divided up into rival blocs of military and monetary power, driven by a psychopathic, dog eat dog logic, means brutal wars in an unstable and rapidly warming world.

In other words, not for the first time in human history, we need a revolution. Slave societies and feudalism, both powerful social systems that survived centuries of crisis, have been overthrown in previous eras. Capitalism and its ruling psychopathic clique will have to follow if we are to avert the worst scenarios awaiting us.

This colossal task has been the project of the most militant and politically radical wing of the working-class movement since the time of Karl Marx. The argument of revolutionaries is that, just as capitalists engaged in competitive accumulation are pushed to adopt a psychopathic logic, workers engaged in collective struggle are pushed by that struggle in the direction of a very different logic, of solidarity and cooperation. The antithesis of the corporate psychopath is the collective worker in struggle.

We get a glimpse of what this looks like in one of the most famous working-class upsurges this country has seen.

‘It is magnificent that so many people think, like the Builders Labourers’ Federation, that the environment must be protected at all costs’

- Jack Mundey, 1972

In my drive around the coal districts, plenty of conversations end with me offering to send a link for Rocking the Foundations. The film tells the extraordinary story of the NSW Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF), from the 1950s up to 1975.

The story starts in 1951 with a small group of communists setting out to transform their union. After years of workplace organising, a reform ticket swept to victory in the NSW BLF in 1961, overturning decades of corrupt, right-wing rule. In the years that followed, a network of politicised militants led strikes that won safety, site amenities, workers’ compensation, decent pay and dignity on major construction sites around Sydney and beyond. The movement was part of a rising tide of union militancy, which was intertwined with a growing, society-wide radicalisation generated by the mass movement against the US and Australian war in Vietnam.

Builders labourers in this era had an extraordinarily high level of participation and control over their union and their industry. In the early 1970s, major construction sites, including the massive Sydney Opera House site, operated under a system of workers’ control, where an elected committee of workers assessed requests from management and organised the work.

In 1971, the BLF placed a ban on the development of Kelly’s Bush in the posh suburb of Hunter’s Hill in Sydney. In the years that followed, builders labourers and other construction workers wrote themselves into the history books, placing “green bans” and refusing to work on environmentally or socially damaging projects. The NSW BLF was smashed in 1974, and most of the green bans along with them. But the legacy of these workers’ struggles is still visible today in streets and parks in Sydney, Melbourne and beyond.

The green bans are an incredible piece of history. They blow apart the myth of the supposed eternal hostility of blue-collar workers to environmental and social justice issues. They demonstrate the extraordinary strength that organised workers can bring to a social movement.

But to tell the story of the BLF in the 1970s is to describe a series of differences with today.

Social issues including climate, war and racism have sparked significant mobilisations in recent years. But there’s been no equivalent of the radicalisation generated by the movement against the Vietnam War, a mass worldwide radical movement that inspired and trained thousands of activists. These activists went on to transform unions and social movements over the following decade.

Even in the early 1970s, most other union officials detested the freewheeling, participatory style of the leadership of the NSW BLF. Few did anything to help the BLF resist deregistration. This conservatism was reinforced by the economic crash of the mid-1970s. Victories became harder to achieve, and the political limitations of Australia’s union movement became more exposed.

Most of the leadership of the union movement had already ditched militancy in favour of collaboration with employers by the early 1980s. Then from 1983, the ALP-ACTU Accord consciously crushed the surviving outposts of worker militancy, dismembering the remaining militant branches of the BLF and other unions.

The legacy of this history is still with us. So, rather than a union movement which rocked the country with a strike wave in 1969 that smashed the anti-union laws and freed union leader Clarrie O’Shea from prison, we find a movement under siege and on the defensive. Some sections are in a state of abject industrial surrender. Rather than radical political currents being well established in important sections of unions, we find well-organised class collaboration dominating. Rather than a rising tide of industrial action, social media and email campaigns proliferate.

Bringing together a union movement at a low ebb with a climate movement which is far from mass or radical most of the time, is not going to recreate the dynamic of the BLF. The rather underwhelming union presence at the largest climate protests in Australian history—the September 2019 school strikes for the climate—is evidence of this. It is, however, possible to work systematically to rebuild the three crucial, interconnected components of the BLF story—class-struggle unionism, a defiant mass social movement and organised radical political currents.

What are our prospects?

It’s easy to be glib about the prospects for a “just transition”. But no-one should be under any illusion about the enormous level of struggle, organisation and radical politics that will be required to win anything that lives up to that name.

For starters, for there to be a “just” transition, there has to actually be a transition. Despite 30 years of platitudes and pledges, the proportion of energy produced by wind and solar worldwide—once we include transport and “stationary energy” (for instance gas burned in home appliances and in industry)—is less than 2 percent. Neale draws on the work of Trade Unions for Energy Democracy when he writes (in early 2021): “We have been told for two decades that the proportion of renewable energy in total global energy has been continually rising. And yet, in 2019 wind and solar produced less than 2% of the total energy used globally. Less than 2%. And that proportion has not been growing. For the last four years, the amount of new wind and solar each year has been flat, and not increasing”.

Eighty-eight percent of global energy still comes from coal, oil and gas. Of the remainder, half is from burning wood and cow dung, mainly in villages in the poorest countries. Most of the remaining 6 percent of global energy is sourced from biofuels, nuclear and hydropower. None of these energy sources are going to get us where we need to be.

The good news is that a transition is possible. The bad news is that the work to achieve it has barely started.

The “just” part of the phrase “just transition”, promising not only a transition but one that affords justice to the workers, is also very far from assured. There’s no guarantee that jobs in renewables will have anything like the conditions in the fossil fuel industries they are meant to replace.

In the US, workers in power stations are paid an average of US$41 per hour, more than double the median wage of US$19 per hour. US coal miners average US$36 per hour. Workers in the solar power industry, by contrast, are paid an average of only US$24 per hour.

In Australia it’s harder to find comparative figures like this. But stories of cut-price operations are widespread in the barely regulated and sparsely unionised renewable sector. A host of private sector construction projects are dispersed all over the country, without union agreements. The Electrical Trades Union says lack of basic regulation means solar farm construction is a “cowboy industry” with “widespread unsafe practices”. It’s a huge organising challenge.

To the extent that decent wages and conditions exist in the carbon economy, they are the product of bitter, protracted struggles in coal mines and oil and gas platforms, in power plants and refineries. Of course, those conditions are under relentless attack—often from the same forces that proclaim their supposed love of “high-paying blue-collar regional jobs”.

Pretty much any new industry, including renewable electricity generation, starts as a mainly non-union endeavour. To win decent wages and conditions in the renewables industry in a world run by psychopaths will take struggles at least as long and bitter as those that have marked the fossil fuel industries over the past century and more.

These battles will have to happen in an industrial landscape that is rapidly and profoundly changing.

We make our own history, as Karl Marx once observed, but not in circumstances of our own choosing. One of those “circumstances not of our choosing” is how crucial the labour of particular groups of workers is, for production and for profit. Struggles over wages, conditions, permanency and safety occur over this ever shifting industrial terrain.

The industrial power of workers in fossil fuel industries is significantly boosted by how crucial their labour is to every productive system. In a coal-fired power station, workers’ labour is essential to production as well as maintenance. If key workers in a power station or the mine feeding it walk out on strike, the electricity will soon stop flowing.

This has a huge impact on the entire economy and society. A strike of a few hundred power station operators can throw production and profits into crisis in an entire state. There is probably no other group of workers with anything like this degree of industrial power.

Of course, working in a power station is not some automatic path to industrial victory. It took the efforts of political radicals, many of them communists, to build strong union organisation in the power stations after World War Two—often in defiance of their own more conservative union leaders. It’s possible for sections of the workforce to be ground down and defeated, as with the maintenance workers’ strike in the Latrobe Valley in 1977, and the South East Queensland Electricity Board dispute in 1985. Once conditions are lost, it takes a serious dispute, like the 100-day lockout at Yallourn in 2013, to win them back. Still, the indispensable role of workers in a power plant gives them a head start on winning decent wages and conditions.

The labour of coal miners and oil and gas workers is also central to the entire economy. However, as coal miners have known for 200 years, the industry is one of booms and busts. And unlike electricity, coal and other fossil fuels can be stored and traded in huge quantities across regions and around the world, allowing management and governments to organise around the effects of strikes.

Nevertheless, local strikes can seriously mess with production chains far removed from the mine. And where mine workers are organised on a big enough scale, and especially when national and international coal markets are tight, coal miners can exercise enormous industrial power because of the potential impact of a strike on electricity and steel (and in the past, other crucial industries such as transport).

All of this is very different from the industrial power of workers in renewables. Once installed, solar panels and wind turbines generate electricity without a production workforce on site. Workers are needed for maintenance – more so on wind farms than in solar—but it would take a long time for a strike in the maintenance workforce to cut the amount of electricity being generated.

This doesn’t make it impossible to organise for decent wages and conditions in renewables, but it’s a big change to the terrain on which the struggle is conducted, and a change that weakens workers’ industrial power.

There are other problems. For most of the twentieth century, the structure of industrial relations laws in Australia—the product of a colossal level of struggle in the decades immediately before and after 1900—meant that a relatively small group of workers could win gains that would then “flow on” to other sectors.

This design feature was intended to contain militancy, by allowing more moderate unions to win gains without taking industrial action. But it meant that militant sections of the class were a vanguard in a very direct way: their gains would very often flow on to other groups of workers. So the impressive wage gains made by the NSW BLF in the spectacular mass strike of May 1970 flowed through to construction workers in other states. Shorter hours won by fitters and turners in the metal trades would flow on to other industries, and so on.

The Hawke/Keating government destroyed this system in the early 1990s. Industry bargaining was replaced with a system of enterprise bargaining, still with us today. Each group of workers has to win and keep its gains in its bargaining unit (usually a single employer or even a single workplace), or face stagnation or going backwards.

Industrially strong and well-organised workers in power stations, mines, construction and elsewhere could keep their conditions intact—for a time, anyway. However, it was no longer the case that gains made by these strong groups of workers flowed through to the less strong. What had in practice been an industrial vanguard, winning gains for the class as a whole, was reduced to strong sectional organisation (at best), which had little direct effect in lifting conditions for the rest of the working class.