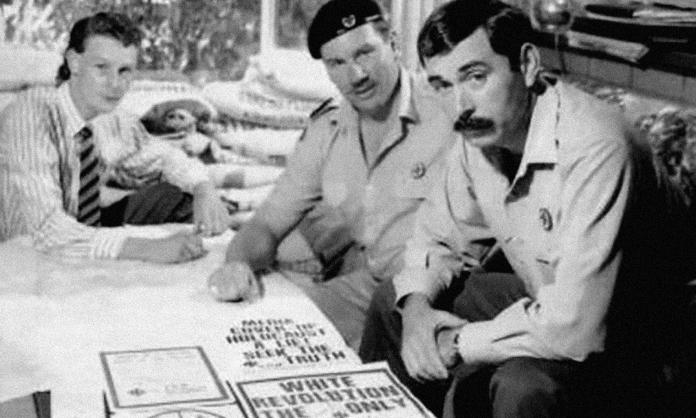

Between 1984 and 1989, tens of thousands of lampposts, letterboxes and bus stops across Perth were covered with neo-Nazi posters bearing slogans such as “No Asians”, “No coloureds”, “White revolution: The only solution” and “Jews are ruining your life”. The poster campaign, initiated and organised by the Australian Nationalist Movement (ANM), was the opening salvo in a campaign of terror that ANM leader Jack Van Tongeren believed would make the city the centre of a fascist revolution.

The ANM believed that there wasn’t much room for an openly Nazi posture—the legacy of World War Two and the strength of the left militated against it. So while its members privately maintained a commitment to neo-Nazi politics, publicly they tried to position themselves as “Aussie patriots”. However, the group’s long-term approach was always wholly neo-Nazi. It was inspired by the lurid fantasies of The Turner Diaries—a work of fiction by American neo-Nazi William L. Pierce, which advocated murder of Blacks, liberal journalists, women and left-wing activists.

The ANM warned of an “Asian invasion”—suggesting that “real Australians” (read: white Australians) were being swamped. This argument didn’t emerge in a vacuum. The ANM’s preoccupation with Asian migration reflected three things: a commitment to a longer tradition of anti-Asian racism in Australian society; the legacy of the Vietnam War; and a growing current in mainstream political life that was determined to push back against multiculturalism.

The ANM claimed to be the inheritor of a tradition of radical Australian patriots, poets and bushrangers of the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Van Tongeren’s autobiography claims that the heroes of the goldfields and the outback were fighting the British colonial government’s attempts to “heavily asianize the Australia colonies”. Figures such as Ned Kelly and Henry Lawson were interpreted as forerunners of the twentieth century’s “White Nationalist guerrilla fighters”.

The Vietnam War had polarised Western Australia as much as the rest of the country. It was a driver of radicalisation among left-wing young people, and the axis around which a burgeoning “New Left” developed. For the political right, the forces of the North Vietnamese and the National Liberation Front represented an active and mobilised Communist-aligned Asian force that threatened Australia militarily and ideologically. Domestically, the growing strength of the radical left was thought to threaten Australia’s traditional values and way of life.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, there were clashes between the right and the left over the war. While many Vietnam veterans opposed the war, the largest organisation of veteran soldiers in Australia—the Returned and Services League (RSL)—was on the right of politics and espoused anti-Asian attitudes. In 1988, for instance, the national president of the RSL, Brigadier Alf Garland, maintained that the government needed to have a more selective immigration policy to keep Australia “predominantly European”.

Van Tongeren was a Vietnam veteran, and the war played a significant role in the development of his politics. After leaving the army in 1975, he developed a virulent anti-communism, and his anti-Asian formulations were often made with reference to the war. In 1985, an ASIO agent tracking Van Tongeren reported that he gave the impression of “a trained military killer ... If his claimed experiences in Vietnam are to be believed, he has a pathological hatred of Asians, especially Vietnamese”.

At the same time, hostility to Asian migration was growing in mainstream political discourse. Historian Geoffrey Blainey is widely singled out as an instigator of the mainstream “debate” about Asian immigration. In early 1984, he gave a highly charged speech in the Victorian town of Warrnambool arguing that Asians were swamping society.

His rhetoric was embraced by a current in conservative Australian political life that was keen to offer a new enemy to those suffering from the privations of the economic crisis of the early 1980s. The leader of the Liberal Party, John Howard, developed an immigration and ethnic affairs policy that reflected the thrust of Blainey’s argument, thus further broadening and legitimising anti-Asian prejudices.

The ANM was thankful for the political space opened by mainstream figures such as Blainey and Howard, but keen to expand it further. Van Tongeren’s book The ANM Story interpreted the public response to the right’s anti-immigration arguments as sympathetic but passive. The role of the ANM, as he saw it, would be to operationalise the anti-Asian racism and to hasten the expulsion of Asians from Australia.

The group’s schema of political action was as follows: a campaign of public propaganda against migration (particularly from Asia), followed by military-style attacks on institutions of social power, such as the courts and parliament. It would then launch a hostile takeover of government and install Van Tongeren as leader.

The propaganda campaign began in 1984, just prior to the official formation of the ANM, with the printing and distribution of thousands of leaflets and posters across Perth. Van Tongeren spends pages in his history of the ANM describing the postering efforts: from the kinds of typeface used, to experiments with different kinds of glue. He writes that in 1984, “the first batch of leaflets went into the general Parmelia, Orelia, and Medina area. A team of skinheads and activists leafleted the area one night. The overall response was not too good at all. So we tried somewhere else. In fact we tried many places. We discovered that we got a far better response from the well to do areas than the poorer areas”.

After such initial experimentation, the campaign intensified. Journalists from the West Australian estimated that between 1987 and 1989 the ANM put up some 400,000 posters, while the courts calculated that the removal of the posters cost local councils and state government bodies up to $130,000.

When interviewed in 1990, Dr Pek Goh—a representative of Perth’s largest Chinese community organisation, the Chung Wah Association—said of the impact of the far-right campaign: “Many people were distressed, particularly children. We are a very visible minority and easily victimised”.

The sense of incipient violence was further heightened after a Malaysian taxi driver, Peter Tan, was bashed to death on 18 February 1988. The murderer, 17-year-old Nicholas Meredith, when asked why he committed the crime, declared: “I don’t like the Chinese to start with. So I belted the shit out of him”. When, despite legal and political appeals from Tan’s wife, Meredith was convicted only of manslaughter, the sense of isolation among Perth’s Chinese population was heightened.

While there was some recognition of the divisive nature of the political campaign waged by the ANM, the historical record reveals a remarkably sanguine attitude from ASIO and the Western Australian police. A 1987 ASIO report maintained that the “threat posed to security by the group is low”. Such an approach seemed to predominate until 1989, despite several reports in Van Tongeren’s files that implicate him or other members of the ANM in violent incidents. After one such incident—a racist attack on a shop in the eastern Perth suburb of Armadale—the policeman involved, Constable O’Neill, described Jack Van Tongeren as “a bit eccentric and full of wind, but basically quite sociable and friendly”.

Van Tongeren’s own account of the situation notes that “in the summer of 1987 the Police pretty well left us alone. In some cases they actually encouraged our plastering up teams in action, even the Skinhead teams—and Skinheads and Police rarely get on well together. Many Police vehicle patrols must have seen our teams in action, but let us carry on”.

Such assertions appear more than wishful thinking on the part of Van Tongeren. In the film Nazi Supergrass, the Labor Minister for Police between 1986 and 1988, Gordon Hill, recounted that during his time in office he “came across quite a lot of racism; usually directed against Aboriginal people. On the question of taking action against people who were engaged in fire-bombings and wreaking havoc within the community, some police officers were loath to take action against these people. Some of my colleagues had the attitude that if we just ignore it, it will go away”.

These attitudes seem to have shifted when the ANM began to engage in more openly criminal behaviour. In 1988, the group decided that the impact of its poster campaign was diminishing and it needed to escalate. Fire-bombing Chinese restaurants was the next step.

In The ANM Story, Van Tongeren described himself and his followers dousing four Perth restaurants with petrol and setting fire to them, and then burning and bombing a fifth. To fund their activities, they launched a series of armed robberies. The police estimated that the ANM stole goods worth $300,000, including building materials, electronic equipment, computers and an “inflatable boat which was to be used on the Swan River, to avoid police roadblocks”.

By mid-1989, the police were taking the activities of Van Tongeren and the ANM more seriously. In July, Van Tongeren was fined $1,700 for possessing explosives and unlicensed ammunition. The following month, he and two other members of the ANM were fined $150 for illegal bill posting.

The intensified police interest provoked escalating levels of paranoia and anxiety among ANM members. In September, an 11-year-old boy playing near a creek in Gosnells came across the body of 22-year-old David Locke, an ANM member who others in the group suspected was a police informant. He was severely bruised, his head bashed in, his throat slit and his hands tied behind him.

The dramatic escalation in violence forced the government to act. The ANM’s activities were attracting attention internationally, and Western Australia’s reputation as a destination for Asian business investment and migration was suffering. Western Australian Premier Peter Dowding was so concerned by the potential economic impact that he wrote to a series of major Asian newspapers to “assure business people and politicians that Asians are welcome in Australia”.

The racist propaganda and attacks by the ANM were largely ignored by police and state authorities while they weren’t disrupting broader social peace, capital investment, regional diplomatic relations and the rights of property owners. But now the group had well and truly overstepped the mark.

By 1990, almost the entire membership of the ANM was on trial. Van Tongeren, John and Wayne Van Blitterswyk, Christopher Bartle, Judith Lyons and Mark Ferguson had all been arrested as part of “Operation Jackhammer”, a high-level police operation established specifically to target the ANM, and William Monaghen and Wayne Napier had been charged with the wilful murder of David Locke. Collectively they were charged with 197 crimes.

When the Operation Jackhammer trial began, it was revealed that there was indeed a “mole” inside the ANM—but it wasn’t the murdered David Locke. Rather, ANM treasurer and third in command Russell Willey had turned police informant. Willey’s testimony provoked an extreme reaction from Van Tongeren and the Blitterswyk brothers, who took to the stand to explain their political philosophy and lambast Willey for his betrayal.

During this testimony, they revealed their plans for inciting a fascist revolution in Perth. A Canberra Times article reported that they talked of “murdering senior police officers and a government minister, of blowing up ships at Kwinana, south of Perth, of nail-bombing a Vietnamese pool hall in Perth, of breaking in to the Maylands Police Academy and stealing weapons, of blowing out the walls of Fremantle Prison and arming the prisoners”.

The six-week trial ended on 14 September 1990 with guilty verdicts for 159 of the charges. Van Tongeren was found guilty of 53 offences—including wilful damage, assault occasioning grievous bodily harm, arson and causing an explosion—and sentenced to 18 years in jail. The racism that motivated all the ANM’s activities barely featured, being mentioned only in the context of “conspiracy charges in relation to a racist poster campaign”.

The response of the state to the ANM’s racist terror campaign remains revealing. We are facing a major, increasingly radical, violent and aggressive element to the far-right COVID denial movement in Australia. It is important to understand how these movements emerged in the past, as both a rejection and an echo of mainstream political life, and how mainstream capitalist institutions both reject and tacitly allow such politics to thrive.

This is an edited excerpt from a chapter in the forthcoming book Fascism and Antifascism in Australia, edited by Jayne Persian, Evan Smith and Vashti Fox.