“The ’60s”. What images this conjures up: youth rebellion; drugs, sex and rock ’n’ roll; radicalism that helped to stop the Vietnam War. But actually, some of the most important events of this decade and the next were workers’ industrial struggles.

Two million people migrated to Australia from Europe between 1945 and 1965. They usually filled dirty, dangerous and soul-destroying jobs for substandard wages and conditions. Disillusionment replaced hope, reviving traditions of class struggle from their homelands. Seventy percent of the 4,000-strong Mt Isa Mines workforce in western Queensland were migrants—47 nationalities in all.

From July 1964 to April 1965, their iconic battle reached into homes around the country. It was one of the most controversial industrial upheavals of the decade. The arch-conservative Courier Mail described the place like this:

“[A] smoke stack and slag heap dominating a township of shabby houses, unspeakable hotels, and inordinately expensive shops. Toss in ... a wretched summer climate, fearsome insect plagues, and great isolation—and it stands forth as a black prince among mining towns.”

It all began over showers. Company-owned homes had no running hot water. Mine showers were assumed to be sufficient, but they were notoriously unreliable. Pat Mackie, the best-known leader of the coming struggle, said that there was nothing worse than cleaning off “coated grease and the dust of the black earth” in a cold shower.

In May 1964, on the third day of hot water running out while they showered, Mackie reportedly stormed into the superintendent’s office dripping with soap. This one angry act stirred the other miners to action. After two threats of strikes by angry unionists, management finally fixed the plumbing.

In July, a large meeting discussed the issues workers were fuming about. Undemocratic control by their union officials in the Brisbane office rankled. And they needed higher wages plus an increased bonus for working in the dangerous lead dust.

In the struggle that unfolded, the shenanigans of Mount Isa Mines, the do-nothing, right-wing Australian Workers Union (AWU), the Industrial Commission, the Industrial Court and the High Court read like a Kafka novel.

The AWU secretly changed the union rules so that delegates couldn’t claim paid leave for union business. Consequently, Mackie was sacked for union activity in work time, which to his knowledge was his right. The union also refused to recognise delegates elected at large members’ meetings, declaring the gatherings illegal. And it joined the press attack on Mackie and other activists as “Reds” (communists) trying to destroy the Australian way of life.

But all the miners wanted was the “fair go” they’d been promised.

On 4 August, the Industrial Commission ruled that a wage increase would be “merely a camouflaged bonus payment”, something that was beyond its power to grant. But five years earlier, the Commission had used the opposite argument! Mackie, in his account of the conflict, Mt Isa, the story of a dispute, noted:

“No bonus because it was a wage increase, no wage increase because it was a bonus. It was clear to every man ... that on whatever basis they made their just claims to a fairer share of the wealth they created, they would get nowhere ... This was, perhaps, the strongest single factor in precipitating the dispute.”

A mass meeting after this “bombshell” decision elected a negotiating team that the union members trusted. They invited members of craft unions, all affiliated to the local Trades and Labour Council (TLC), to the next meeting to discuss action around their common demands. And the miners voted to affiliate to the TLC in defiance of their Brisbane officials, who persistently refused to cooperate with the other unions.

When the company refused to discuss a pay rise, the negotiating team presented it with the meeting’s decision: men working on contract would exercise their legal right to move onto wages.

The gist of it was this: the men, now earning about half what a contractor could, maintained production at the level expected for wages. Inevitably, output fell—contract work pushes workers to speed up and work longer for better pay, thereby increasing profits for the bosses.

For months, they became, in Mackie’s words, “bogged down in tortuous, fruitless legal argumentation”. The company argued in the commission that the workers’ wage move was tantamount to a strike. Legally, it was no such thing.

The union expelled Mackie, but the workers continued to regard him as their leader. On 21 November, frustrated by the AWU officials’ treachery, they set up a Council for Membership Control of the AWU (CMC). Union meetings became by default CMC assemblies. Mackie wrote that, in doing this, the workers had “got the bit between their teeth for the first time”. They would not surrender lightly.

Two days later, for the third time, the Industrial Commission ruled in the workers’ favour on the contract issue, noting that what they were doing could not be considered a strike. Even the one dissenting commissioner admitted that they could not order the men to work on contract because the award allowed them to choose contract or wages.

The company immediately appealed to the Industrial Court. Presiding Justice Hanger virtually instructed the commissioners to overturn their ruling. They dutifully did what they had ruled impossible days before and instructed union members to stop “taking part in an unauthorised strike”.

Near the end of 1964, the Nicklin Country-Liberal Party government declared a state of emergency. Anyone refusing to work on contract faced a £100 fine or six months in jail. Gordon Sheldon, the company’s public relations officer, wrote that, at the next union mass meeting, AWU officials could not make themselves heard over the “jeering, yelling, catcalling”. They left “looking angry and perplexed”.

Mackie was confirmed as the chair and order reigned, making redundant the huge contingent of cops assembled to suppress the expected mayhem. The workers voted overwhelmingly to refuse to work on contract without the wage rise, Mackie’s reinstatement and improved contract conditions.

The meeting, and all future ones, became a public affair—including women and children, journalists, company staff and even some businesspeople.

Women formed a support organisation that at times had 100 attendees at its meetings. They voted in union meetings, holding up the children’s hands to participate, and affiliated to the Mt Isa TLC, to which they sent delegates.

The defiance and unity, plus the expectation that the company would have to negotiate, created a carnival atmosphere. But two days later, 2,700 were locked out and the company closed the mine.

The biggest meeting ever seen in the town, about 4,000, ensued. All 14 unions in the town established relief committees. And support from around Australia poured in—messages, union donations, some voting to levy all members a percentage of their wages, money immediately collected at work. The women recorded and distributed all money.

There were some sympathy strikes and union actions, but nowhere near enough, minimising the pressure that could have been put on the government.

A second state of emergency was declared on 27 January 1965, following the company’s announcement that it would open the gates to workers who agreed to the old conditions. Anyone in the Mt Isa-Cloncurry area could be arrested without warrant if, “in the opinion of a police officer” they were a threat to law and order. No appeal was allowed.

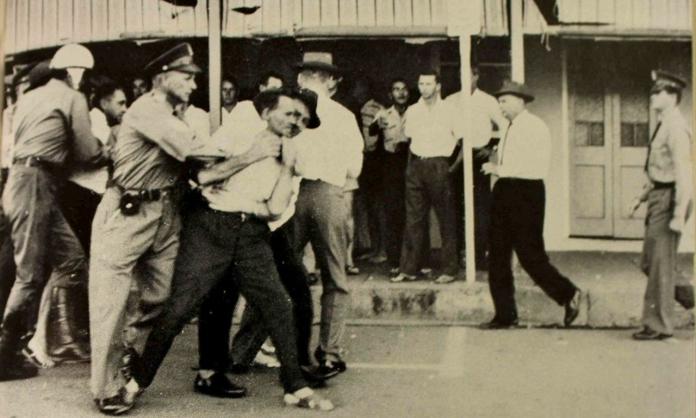

Political squads of police descended on the city, turning it into a mini police state.

Mackie and John McMahon, the president of the local TLC, who were away building support for the miners, were barred from returning to their homes in Mt Isa! This provoked an incredible outpouring of anger and bitterness around the country. It was on the front pages of every newspaper, dominating radio and TV broadcasts. Mackie became a household hero, at least in working-class households.

The Queensland TLC called for a statewide general strike, and the response was massive. Widespread union actions looked like they could become a national workers’ mobilisation.

Rather than forcing men back on contract, the draconian provocation had hardened their determination.

Some of the press turned against Premier Nicklin. But the ABC was the most strident purveyor of company lies to the end. Only later was it revealed that its “correspondent” was Sheldon, the company PR officer!

Mt Isa Mines threatened to sack the 800 men working above ground if insufficient numbers turned up to work on contract. Police, in effect acting against the government’s state of emergency, negotiated with unionists to allow a mass meeting. Fred Thompson, the popular north Queensland organiser of the Amalgamated Engineering Union, seemed to sense the need for a positive note:

“If nothing else emerges from this dispute other than the wonderful spirit of understanding and brotherhood between the different nationalities which comprise our community, then we will still have made a tremendous gain.”

Enthusiastic clapping and cheering indicated the pride workers took in this.

With police having undermined the government, and with growing unrest about the dispute, a secret cabinet meeting suspended the state of emergency. Pete Thomas, author of a pamphlet titled Storm in the Tropics gloated: “The Nicklin government wilted and cracked. It had set out to be a Napoleon—only to find itself within a week, a Humpty Dumpty instead”.

Two Sydney wharfies drove Mackie 3,220 km through arid lands into Mt Isa, evading police blockades. Two Italian militants hid him until he could attend a mass meeting, causing a sensation.

Picketing became necessary. From 17 February, every morning for two months, hundreds of men and women turned up to confront hundreds of cops.

Endless hearings and appeals in the Industrial Commission and Court, from which the Mt Isa delegates were excluded, dragged on.

Then on 17 March, at the urging of the AWU, the government banned picketing. Printed material urging workers not to return to work was banned. But a Finnish language news sheet continued to appear. Police raided homes, without warrants, day after day looking for their printing machine. Women and children took the brunt of their brutality. But the cops could never break their nerve and never found the “criminal” equipment.

With the courts openly supporting the company, the police given police-state powers and the AWU conniving to get scabs from out of town, strikes and bans on the movement of copper were the minimum needed to win.

But this was 1965; the upsurge of working-class radicalism was still to come. Unions were intimidated by threats of fines under the Penal Powers (which would be smashed by a general strike in 1969).

Mackie was committed to nonviolence and avoiding arrests, so he argued that the ban on picketing meant there was no alternative but to return to work. If they didn’t, scabs would undermine their traditions of solid trade unionism.

At a subdued meeting on 7 April, craft unionists voted, “with grim resignation”, 200 to 70, to accept the Queensland TLC’s recommendation to return to work. A narrow majority at the AWU meeting followed suit in a mood of “deep smouldering disgust and indignation”.

Dozens, including Mackie, could never again work in Mt Isa. But there were gains.

Management did not dare treat the workers with the contempt of the past. The contract system was overhauled, making it transparent and on better terms. Workers did get a pay rise, though less than they wanted. And the women’s committee continued campaigning for improved conditions in the city.

Other less tangible gains were of supreme importance. The unity they achieved demonstrated the transformative role of workers’ struggle. And their stand contributed to a growing tide of industrial struggles. At its peak in the early to mid-1970s, workers’ share of national income reached the highest in Australian history.

It stands as part of a proud history of migrant organisation and leadership of both migrants and Australian-born workers.

Struggles such as this build confidence and pride, reflected in the words from two of the participants. Sylvia Viani said 25 years later:

“I do not regret a thing ... If you cannot stand up for your rights, you may as well never have been born.”

And Pat Mackie concluded:

“The spontaneity of the Isa people’s rebellion ... the spontaneous organising of the wives, in taking the matter of their own freedom into their own hands ... was a living lesson in the constructive social potentialities of rank-and-file working people. It was a triumph of the human spirit.”