The system of South African apartheid—the political and economic rule of a small minority of white people over the Black majority—was one of the most heinous ever to have existed.

Black people were stripped of national citizenship, instead designated as citizens of artificial “Bantustans” (or “homelands”). They were robbed of the right to vote and form trade unions, and their political organisations, like the African National Congress (ANC), were banned. They were allowed to reside or work in “white” areas (most of the country) only with a government pass. If found without a pass, they were arrested, beaten and deported back to the Bantustans. These laws were enforced by a brutal police force and military, which were twice given extraordinary powers in government-decreed states of emergency.

This brutal system, which began in 1948, was eventually demolished in the early 1990s. It was brought down by a mass working-class movement, not simply top-level negotiations by political leaders, as is often taught. The struggle against apartheid holds important lessons for political movements today. Here are a few of them.

Lesson #1: Apartheid was a product of capitalism

Most histories paint apartheid as a peculiar aberration. Yet, elements of it prevail today in Palestine, and racism in various forms plagues all capitalist countries. Apartheid in South Africa was an extension of this structural racism, designed to meet the particularly brutal needs of South African capitalism.

The profits of the white capitalist class were made off the backs of highly exploited Black workers. For a long time, South Africa’s most valuable export was gold, which Black miners dug out of the ground in gruelling conditions and for minuscule wages. In the 1940s, workers fought back and challenged the racist laws that prevented them from residing in certain areas or accessing skilled jobs.

The response of the ruling class was to double down on the repression of Black workers. By controlling the mobility of the entire Black population through the pass system, they could prevent workers from organising against their horrific conditions, as well as direct the unemployed into industries that needed a greater supply of labour. The need to preserve the rule of a small minority, along with the logic of profit accumulation, combined to create the racist apartheid system.

Although racism is built into capitalism everywhere, the even more brutal and codified system of apartheid was necessary because the white South African capitalist class found themselves in an extreme minority, not only economically but also racially. As Jan Lombard, one of the chief ideologues of apartheid, put it: “If an unqualified one-man, one-vote election was held today in the Republic, a non-white leader with a communistic programme would probably attain an overall majority on a pledge to confiscate and redistribute the property of the privileged classes”.

Lesson #2: Apartheid was ended through mass working-class struggle, not peaceful negotiations

“What the bourgeoisie therefore produces above all are its own gravediggers”, wrote Karl Marx in the Communist Manifesto, referring to the working class. You could say the very same about apartheid. By so openly and brutally repressing the majority of South Africans, apartheid laid the basis for its eventual overthrow.

From 1973 onwards, Black workers began to organise. That year, a great strike wave broke out in the southern port city of Durban, which laid the basis for new independent (and illegal) unions. Over the next two decades, these would swell to become one of the biggest and most militant workers’ movements in the world.

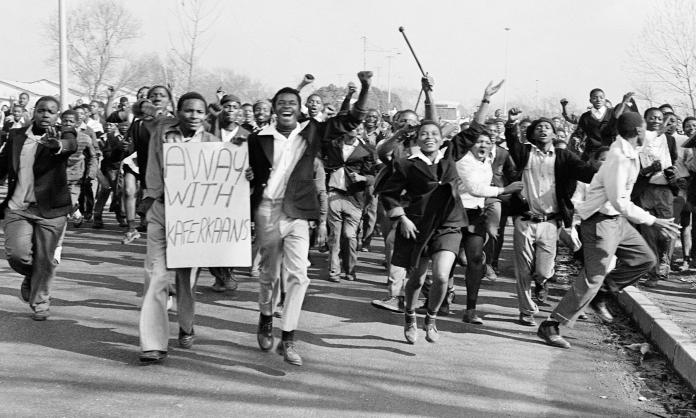

School students and young people joined the struggle, often playing a particularly heroic role. The students of Soweto, a million-strong Black township outside Johannesburg, who in 1976 led a mass school walkout of 20,000 students, deserve special mention. Their decision to riot after police fired live rounds into their protest—killing 23 of them—sparked a nationwide rebellion that took months to put down. School boycotts and youth uprisings in the Black townships that began in the 1980s made sections of South Africa simply ungovernable.

This militancy and radicalism infected the workers’ movement, which by the early 1980s had exploded in size; by 1985, the trade unions had 800,000 members. In November 1985, students and workers in the Transvaal, the country’s mining and industrial heartland centred on Johannesburg, organised a stay-away (meaning everyone stayed at home). An estimated 300,000-800,000 people answered the call.

Two sections of the working class were particularly important: the mineworkers and metalworkers. In 1987, metalworkers in the Mercedes auto factory in East London won a gruelling nine-week strike. Three years later, the firm’s boss complained, “We have had a factory with worker control since 1987”. He detailed in an interview with the South African Labor Bulletin: “Supervisors used to clock in and then lock themselves in their offices for the whole day. They didn’t dare go out on the assembly lines”. When ANC leader Nelson Mandela was released from prison, workers fought for the right to make him a car. The car was completed, to the shock of management, with only a fraction of the usual faults.

By 1987, South Africa was on the brink of revolution. The capitalists were terrified and vacillated between offering concessions (but absolutely not the right to vote) and heightening repression.

A mass working-class and popular movement made the legal system of apartheid untenable. South African rulers were terrified that they might lose not just political power, but their economic power also. The recognition of this by the last white prime minister, F.W. de Klerk, was the “pragmatism” for which Western liberals lauded him when he died. Even when negotiations with the ANC began, the Nationalist Party government refused to concede the basic democratic right of “one person, one vote”. It took yet more political general strikes by workers to drag the government kicking and screaming into submission.

We’re taught that it is “great men” who make history. But it was neither apartheid’s last rulers, nor even just the anti-apartheid leaders like Mandela, to whom we owe a debt. It was ordinary people, waging a relentless struggle, who brought down apartheid. This has been the case for nearly every progressive change—whether it is universal suffrage, the abolition of slavery, trade union rights, decolonisation or anti-racism.

Lesson #3: The movement inspired solidarity across the world.

When white troops fired on Black protesters in Sharpeville in 1960 and when police killed 12-year-old Hector Pietersen during the Soweto uprising, the brutality of apartheid was exposed to millions across the world. Coinciding with the political radicalisation of the 1960s and ’70s, these events sparked an international solidarity campaign that highlighted Western complicity with South African apartheid.

In many countries, this was organised by the trade union movement, student radicals and Black activists. Here in Australia, opponents of apartheid organised a boycott of the white South African rugby team, the Springboks, when they toured Australia in 1971. The white rugby players soon found themselves flown around by the military and without a hotel to stay in, as the hotel, liquor and transport unions refused to assist the tour. Two leading members of the Builders Labourers Federation were arrested for attempting to saw down the goal posts at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

In 1986, the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group set up a permanent picket of the South African high commission building in London’s Trafalgar Square. The picket lasted for four years, until Mandela’s release in 1990.

The campaigns of global solidarity may have played only a small part in the struggle against apartheid, but they were important steps in building anti-racist and radical politics in their own countries and gave heart to those fighting in South Africa itself: they understood that they had supporters around the world.

Lesson #4: Ending legal apartheid wasn’t enough

Nelson Mandela was declared the first Black president of South Africa on 10 May 1994, after the first election in which Black people had the right to vote. The ANC won 62 percent of the vote. This was rightly regarded as a momentous event in the fight against injustice.

However, ending the legal framework of apartheid could only be a first step. Apartheid had massively impoverished Black South Africans. In 1990, 42 percent of the population lived in poverty, Black unemployment was 37 percent, and only one in five Black households had running water. The anti-apartheid movement had always fought, not just for legal equality, but for real economic and social equality.

The platform the ANC was elected on appeared to recognise the need for drastic change. It promised a massive investment in housing and welfare. But the ANC was hamstrung by its own decision not to challenge the wealth and economic power of the white elite. Long before being elected, ANC leaders met with representatives of South African capitalism, such as Anglo-American, the multinational mining corporation. Mandela and other ANC leaders publicly assured the capitalists that they were not socialists and would not nationalise corporations. Once in power, they delivered on these promises. Neither the first ANC government nor successive governments since have tried to improve substantially the lives of most Black South Africans.

When platinum miners at the Marikana mine went on strike in 2014, the ANC government sent in police to break it up. They massacred 34 workers—the greatest single use of lethal force by the state since Soweto in 1976. Cyril Ramaphosa, former head of the National Union of Mineworkers in the 1980s, had by then become one of the board directors of the mining company that workers were striking against. He is now the country’s president.

Capitalism everywhere relies on and perpetuates racism, inequality and misery. Winning real equality would have meant seizing and redistributing the wealth of the mining and industrial bosses—wealth generated by Black workers themselves.

This was possible in South Africa. Millions of workers were organised into trade unions by the late 1980s, and a significant minority were not only willing to struggle for the end of apartheid, but were inspired by a specifically socialist vision. However, this was counterposed to the vision of the ANC and the Communist Party, who sought to limit the struggle to narrowly ending apartheid. These former radicals then went on to establish themselves as the next ruling elite.

Meanwhile, about two-thirds of Black South Africans are languishing in poverty, according to the South African Human Rights Commission. The World Inequality Lab reported in 2021 that the richest 1 percent have likely increased their share of wealth since the end of apartheid.

The millions of Black workers and students who fought with such heroism and bravery should be celebrated by all those who despise injustice. But to do away with systems of oppression entirely, an even greater struggle against capitalism is required.