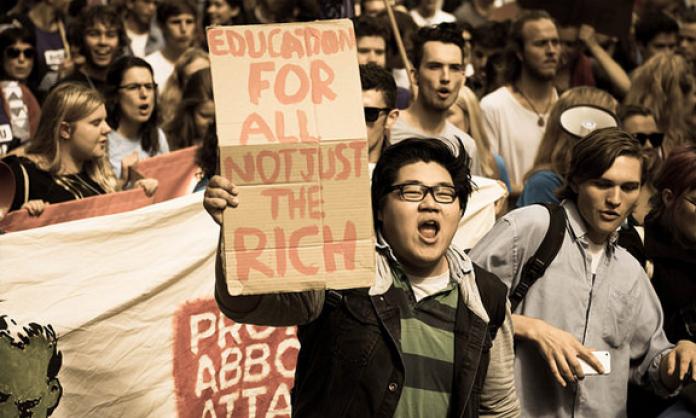

For decades, Australian politicians and university administrations have championed policies to corporatise Australian universities and generate ever more profit from tertiary education.

In 2014, university revenues totalled more than $25 billion. Vice-chancellors have boosted these by treating international students as cash cows, increasing the burden domestic students bear for the cost of their education and by finding ways to cut costs.

Traditionally, this drive for profit has led to course cuts, larger student-staff ratios, an increasingly overworked and casualised workforce and fee increases.

Fee deregulation was the centre of Liberal government policy, and would have allowed universities to charge whatever they liked. Fortunately, deregulation has been forced off the agenda for the time being.

But rather than demand more public funding, vice-chancellors have become fixated on implementing structural changes to improve the “efficiency” of their institutions. University managements are looking to push more students, now seen as customers, through their degree factories at a faster rate to increase profits.

One way of doing this is to change the way courses are delivered – the introduction of video lectures, or the abolition of lectures altogether, for example. Administrations have cynically pitched these measures as attempts to be responsive to students’ needs and to overhaul outdated and boring teaching methods.

In reality, replacing in-person lectures with online classes, seminars or some other system is all about the bottom line. A quick glance at current pay scales for staff at Melbourne University reveals that casuals, who now make up more than 50 percent of the workforce, are paid 30 percent less to teach tutorials than large lectures.

The example of Adelaide University, where lectures began to be phased out in 2015, followed by the abolition of paid academic consultation hours, shows how scrapping lectures can be the opening shot in further attacks on jobs and the quality of education, as students have fewer opportunities for contact with their lecturers than ever before.

Then there is the proliferation of online degrees. Not only are these courses cheaper to provide, but once the infrastructure for them has been established, they pave the way for universities to make mega-profits.

Swinburne Online, established as a joint venture by Swinburne University and the education and training company SEEK in 2014, is a good example. With no limit to how many students can be crammed into a virtual classroom, online courses give universities the ability to enrol huge numbers of students and maximise the financial gain. In the first semester of Swinburne Online’s operations, for example, SEEK’s profits grew 47 percent to $78.7 million.

But what has been the impact of online degrees for students? Last year, the Australian Financial Review reported that the “dropout rate for first-year bachelor students for Swinburne University as a whole has risen sharply” – a predictable outcome of the lack of student support and access to staff.

Many universities have introduced trimesters, or have even moved to divide the academic year into quarters – pushing more students more quickly through their institutions. In the eyes of the administrations, trimesters promote “efficient” use of university resources and buildings. Why have three-month summer breaks when you could operate and charge fees for the whole year?

Of course, increased teaching periods also inevitably mean increased staff teaching hours. Where trimesters have been introduced, at 10 Australian universities so far, the result has generally been a larger workload for staff, shorter time frames in which to deliver the same material and increased student numbers. With overburdened staff comes worse quality education for students. This is without even mentioning the more intense exam periods with less time for students to complete assessment, as well as the trend towards night and weekend exams.

Trimesters also restrict access to education. With government funding for student support at historically low levels and maximum payments set at a measly 42 percent of the poverty line, and with Austudy and youth allowance harder to qualify for than ever before, many students badly require the holiday periods in order to work and save money to support their study.

Corporatisation has also given rise to vertical degrees, sometimes described as a US-style system, with many universities introducing generalised undergraduate courses, requiring students to undertake additional and costly postgraduate degrees. Melbourne University pioneered this kind of “reform” with its notorious “Melbourne Model”, which transformed dozens of undergraduate courses into postgraduate-only degrees, trapping students into paying more and studying longer for the same qualifications.

Most structural changes at universities, including faculty mergers, have led to huge job losses in both administration and teaching. This is because one of the tried and true formulas to increase profitability is getting fewer staff to do more work for less pay. Staff cuts have been pursued regardless of the huge annual profits posted by most universities. For example, in December, the University of Western Australia announced that it would be sacking 300 staff to “cut costs”, despite posting a $90 million surplus.

For the last 30 years, successive governments have defunded university education, but it is hardly as if the university managers are pauperised and helpless. Despite their claims, vice-chancellors do not need to undertake structural changes to stay afloat. In fact, vice-chancellors have been the beneficiaries of the profits flowing from an increasingly corporatised and “for profit” higher education system. Michael Spence, the head of Sydney University, increased his pay by $120,000 in 2015, to $1.3 million a year.

Structural changes won’t solve the problems created by decades of neoliberal economic policy that have turned universities into profit-driven businesses and resulted in lower quality education at a much higher price. Restructures do, however, bring university managers one step closer to their dream of a fully deregulated and privatised education system. Students and staff don’t need structural changes; they need a fully funded public education system that isn’t run for profit.