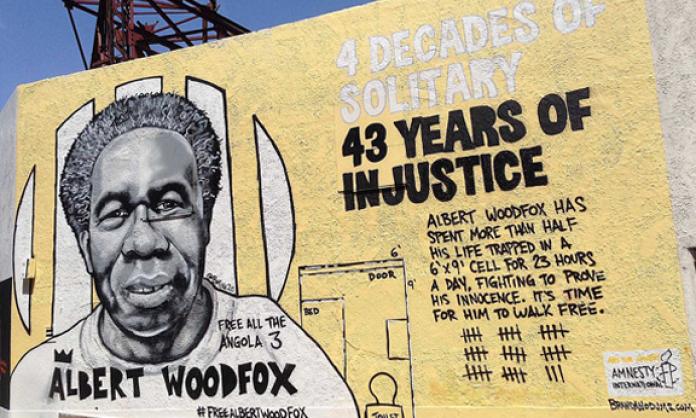

On his 69th birthday, Albert Woodfox was finally released from the notorious Angola state prison in Louisiana. He had been imprisoned for 45 years, 43 of which were spent in solitary confinement – the longest time of any prisoner in the US.

He and another prisoner, Herman Wallace, were convicted in 1972 of killing a prison guard, Brent Miller, in a trial that was a farce. There was no forensic evidence against the two Black men, and the testimony against them by other prisoners was made in exchange for reductions in sentences and other perks. The main witness was granted a pardon and released as a reward for his perjury.

Their real crime was forming a chapter of the Black Panther Party in the prison, and organising against the horrible conditions in Angola. They were later joined by another prisoner, Robert King, and the trio became famous as the Angola Three. All three were in solitary for decades.

He said he read “history books, books on Malcolm X, Dr Martin Luther King, Franz Fanon, James Baldwin – you know just any kind of literature that I could basically get ahold of”.

For many years, Amnesty International and other groups campaigned to free them. King, who spent 29 years in solitary, was released in 2001 when his conviction was overturned. He spent the years after his release campaigning for the release of Woodfox and Wallace.

Wallace, who was held in solitary for 40 years, was freed in 2013 and died of cancer three days later.

The campaign and the facts it brought to light eventually convinced the widow of the slain guard that the two men were innocent. She released a statement last June saying, “I think it’s time the state stop acting like there is any evidence that Albert Woodfox killed Brent”.

Woodfox’s conviction was overturned twice by federal courts, in 1998 and again in 2008, but each time the racist Louisiana authorities retried him and he was again convicted on the discredited “evidence”.

Angola prison is so named because it was erected on the site of a slave plantation called Angola, most of the slaves of which were captured in that African country. It was built in 1901, and throughout the long period of Jim Crow segregation became known as a “hellhole” – especially for Black prisoners. Many were killed by guards.

In 1971, the American Bar Association described the conditions in Angola as “medieval, squalid and horrifying”. These were the conditions that Woodfox, Wallace and the other members of the prison chapter of the Black Panther Party were protesting, which led to the frame-up of Woodfox and Wallace in 1972.

Panther militants

The Black Panthers were originally a Black nationalist group in Oakland, California, set up in 1966 by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, to counter police violence against African Americans.

They began to organise armed patrols, following police to inhibit any misconduct. You can imagine the consternation among the police and government authorities. The first action that gained national attention occurred when a group of Panthers sat in the observation gallery in the state capitol with their (unloaded) guns.

In the context of the burgeoning Black Power movement, the example of the Panthers soon spread nationally, especially among Black youth.

It had become such a force that J. Edgar Hoover, the viciously anticommunist and racist head of the FBI, called the party “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”. He supervised an extensive program of surveillance, infiltration, perjury, police harassment, frame-ups, assassinations and many other tactics to discredit and criminalise the party.

Government repression initially contributed to the growth of the party because killings and arrests of Panthers increased support for the party in the Black community and the political left. Its high point was reached in 1970, with thousands of members and offices in 68 cities.

It also inspired Blacks in the prisons, who organised chapters, largely spontaneously. Woodfox joined the Panthers shortly before his incarceration for armed robbery. People who know him said he was a changed man after joining the Panthers – no longer a criminal but a political activist.

This conversion is reminiscent of Malcolm X’s earlier conversion by the Nation of Islam from a criminal in prison to a militant Black nationalist.

The Angola Three decided that they would cope with solitary by focusing, not on their surroundings and predicament, but on keeping abreast of what was happening in society. Woodfox credits this decision for keeping them sane. Solitary drives many people crazy.

Another factor was that they could read. This “was one of the tools we used to remain focused and to stay connected to the outside world”, Woodfox said in an interview on Democracy Now! after his release. He said he read “history books, books on Malcolm X, Dr Martin Luther King, Franz Fanon, James Baldwin – you know just any kind of literature that I could basically get ahold of”.

Woodfox and King are pursuing a lawsuit against their cruel and unusual punishment. Forty-three years in solitary certainly meets that definition.

I’ll give the last word to Robert King, who was on the same program and talked about what it meant to him that Woodfox was finally freed. King was in the crowd that greeted Woodfox on his release, and said the occasion “was joyous … It was a good thing for the crowd. It was a good thing for me personally.

“It was a victory for justice finally being rendered, if you want to call it justice. Justice delayed of course, justice delayed is justice denied. But nevertheless, it happened … Albert is here now, and he is acclimating himself to his new environment.”