Old England’s in a dreadful state

Wherever we may go;

Thousands of honest working-men

Are brought to grief and woe.

There never was such sad distress

In England before;

Then why should not the rich begin

To help the starving poor.

What will become of England

If things go on this way;

Thousands of honest working men

Are starving day by day!

They cannot get employment,

For bread their children crave,

And hundreds they have died of want

And now lie in the grave.

In many a humble dwelling

Distress does nosw prevail,

For there’s many a family starving

In England and in Wales;

In a land where there is plenty

Of wealth and golden store,

I think it’s time there’s something done

To help the starving poor.

We read that the Welsh miners

Are in dreadful state,

No food nor clothing scarce have they,

No fire in the grate; And many hundred families

To the workhouse they have gone

For shelter for their little ones

From this cold winter storm.

Some have money plenty.

And still they crave for more.

They will not lend a helping hand

To assist the starving poor;

They pass him by just like a dog.

And on him cast a frown.

That’s the way the working men

Of England are kept down.

There’s great distress in Lancashire,

For many miles around;

The masters they’ve done all they can

To crush them to the ground.

Their money is so powerful,

And it destruction buys,

Thank God it cannot purchase life,

Or none but poor would die.

Let us hope our rulers will

Assist the starving poor.

And set the wheel of trade in motion

Which has been done before.

There is plenty of land in England.

Preserved for the game,

And if they would cultivate it,

The trade would mend again.

– HP Such, machine printer and publisher, Union Street, Boro’

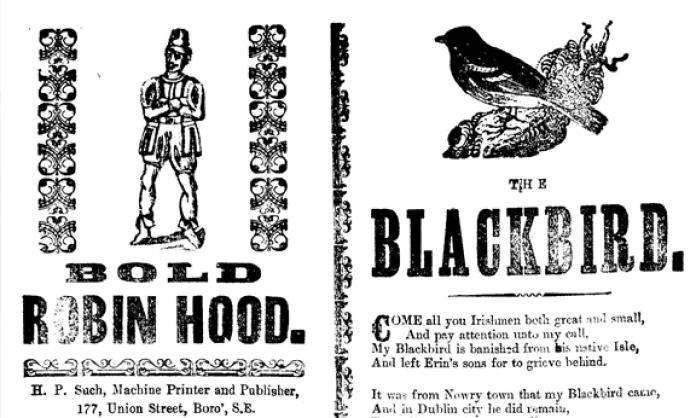

Ballads like this one published in Borough, London, by the famous printer HP Such, had been sold on the streets of the towns and cities from which convicts were transported to Australia from the First Fleet onwards. This street literature was hawked for less than a penny and was sung, or “chaunted” by the seller to a large audience, many of them income poor.

HP Such’s ballad provides us with a sample of the early industrial working class’ emotional and political understanding of the rising empire. Poor wages and famine conditions are contrasted with the wealthy ruling class’ refusal to help: “Hundreds they have died of want and now lie in the grave”. There is famine in Lancashire and “the masters they’ve done all they can to crush them to the ground”. The Welsh miners “are in dreadful state, no food nor clothing scarce have they, no fire in the grate”.

The haughty rulers made the laws that allowed them to enclose the common land as their own – “there is plenty of land in England preserved for the game” – land stolen from towns and villages, resulting in the impoverishment of the poor and the enrichment of the new owners.

Highlighted in the ballad is class war, “war on the workers” writ large. We can clearly see this kind of vernacular verse as agitation for change. The philosophical approach of the composer is clear enough – an exploited community under deadly attack is contemplating what is to be done.

“In a land where there is plenty of wealth and golden store, I think it’s time there’s something done to help the starving poor.” We can find in these ballads assumed rights that are considered more important to the culture than the plethora of laws passed by the rich to protect their ill-gotten wealth.

These assumed rights found expression in food riots involving confiscation and redistribution to the community, in community support for the poaching of game, in the Luddite machine-breaking to preserve employment and in working class song and poetry. Included among the assumed rights are those that Irish rebels claimed through generations of attempts at national liberation, again accompanied by a wealth of song and poetry.

Archives of such vernacular verse are today available online, but two published collections stand out.

In 2000, the Australian folklorist, historian and publisher Hugh Anderson released Farewell to judges and juries – a selection of 140 such “broadside ballads” that related to transportation to the new colony. They document the lives and times of many of the men and women who became the British empire’s forced labour for the first 50 years of the colony.

They are invaluable documents that enable us to understand something of the horror of being exiled to the other side of the globe, never to return or meet family and friends again. They are a voice from below that contends with the vast official documentation of the colonial prison regime.

Another collection of such street ballads, titled A book of scattered leaves, was published in the United States by collector James Hepburn, who selected 120 street ballads that dealt with poverty, famine and the working and living conditions of men and women in the towns and cities of 19th century England.

The ancient continent where the convicts were exiled had long been a land of vibrant poetry and song, which constituted the ceremonial lives of the Indigenous custodians. Unbroken generations of multilingual Aborigines were brought up in language and ceremonial culture – as all humans had been in the thousands of years before the written word. Not that this vibrant artistic and self-sufficient civilisation meant much to the invaders, whose mission was imperial conquest and theft under the classical guise of delivering civilisation to the ungodly – a quest that would create for British rulers the world’s most extensive empire to that point.

Convicts’ concern

It should come as no surprise that an early example of convict poetry, “The exile of Erin”, was published in the Sydney Gazette in 1828, posted to the editor from the agricultural penal settlement at the foot of the Blue Mountains, “the plains of Emu”, as the emotional ballad has it.

Early Australian newspapers are full of song and poetry, much of it composed by their local readers. I have based much of my research on discoveries I have made by delving into this archive and drawing on more than 150 newspaper titles. In the process I have discovered hidden material, now published in my PhD thesis titled “Australian working songs and poems – a rebel heritage”.

The Irish convict Francis MacNamara, a coal miner transported to Botany Bay in 1832, soon gained fame among his fellow prisoners for his extempore verse. He reflects on the convict system under which he experienced the most brutal punishment, including a secondary transportation to Port Arthur. Not surprisingly, his poetry speaks of tyranny and injustice.

One of his early compositions is “Labouring with the hoe”, which undoubtedly alludes to his experience of being assigned to John Jones on arrival. He details the injustice of his own transportation and forcefully proclaims the nature of his punishment in chains as akin to slavery.

Despised rejected and oppressed

In tattered rags I’m clad

What anguish fills my aching breast

And drives me almost mad

When I hear the settler’s threatening voice

Say Arise to labour go!

Take scourging convict for your choice

Or work the labouring hoe

Growing weary from compulsive toil

Beneath the noontide sun

While drops of sweat bedew the soil

My task remains undone

I’m flogged for wilful negligence

Or the tyrant calls it so

Oh what a doleful recompense

For labouring with the hoe …

You generous sons of Erin’s isle

Whose heart for glory burns

Pity a wretched exile

Who his long-lost country mourns

Restore me heaven to liberty

Whilst I lie here below

Untie this clue of bondage

And release me from the hoe!

His most famous and longest verse was “A convict’s tour to hell” – a hilarious description of all the tyrants he met in the prison system ending up in hell … a place where convicts were not allowed:

You prisoners all of New South Wales,

Who frequent watch houses and gaols

A story to you I will tell

‘Tis of a convict’s tour to hell.

The first person the poet meets on his way to hell is the ferryman Charon, who gladly rows him across for free on account of his prestige. The second is the recently departed Pope, who is in charge of “Limbo, or the Middle State”. He won’t allow the poet to stay, saying:

This place was made for Priests and Popes

’Tis a world of our own invention

But friend I’ve not the least intention

To admit such a foolish elf

Who scarce knows how to bless himself …

Frank then bid the Pope farewell

And hurried to that place called Hell

Moving on to “that place called hell”, Frank catches the attention of the devil

When the Devil came, pray what’s your will?

Alas cried the Poet I’ve come to dwell

With you and share your fate in Hell

Says Satan that can’t be, I’m sure

For I detest and hate the poor

And none shall in my kingdom stand

Except the grandees of the land.

The devil urges the poet to take a tour of hell before he moves off to heaven

Hark do you hear this dreadful yelling

It issues from Doctor Wardell’s dwelling

And all those fiery seats and chairs

Are fitted up for Dukes and Mayors

And nobles of Judicial orders

Barristers, Lawyers and Recorders

Here I beheld legions of traitors

Hangmen gaolers and flagellators

Commandants, Constables and Spies

Informers and Overseers likewise

In flames of brimstone they were toiling

Doctor Wardell is the famous Sydney lawyer who is commemorated with a marble plaque in St James Church on the South Wall. Oddly enough, the English convict John Jenkins, who was hanged for the murder of Wardell, is in heaven, as the poet discovers when he finally meets St Peter:

Cried Peter, where’s your certificate

Or if you have not one to show

Pray who in Heaven do you know?

Well I know Brave Donohue

Young Troy and Jenkins too

And many others whom floggers mangled

And lastly were by Jack Ketch strangled

Peter, says Jesus, let Frank in

For he is thoroughly purged from sin

And although in convict’s habit dressed

Here he shall be a welcome guest.

Feted as he is in heaven, the poet finally wakes up to find his adventure was but a dream. It’s hard not to imagine the sheer pleasure convicts would have enjoyed on hearing this great poem, and hear it we know they did, since they memorised it or parts of it well enough for 19th century collectors to copy it down and piece it together.

It was not published until 1890, slipped in as it were with a scurrilous verse by the poet Henry Kendall. Today we have what is considered to be the original handwritten version of this masterpiece dating from 1839, which now resides in the Mitchell Library in Sydney.

We also have a growing understanding that the early working class can be better understood when attention is paid to the wealth of popular poetry and songs that reveal the concerns and passions that accompany their development.

Mark Gregory’s research into early working class poetry and song can be found at www.works.bepress.com/markgregory.