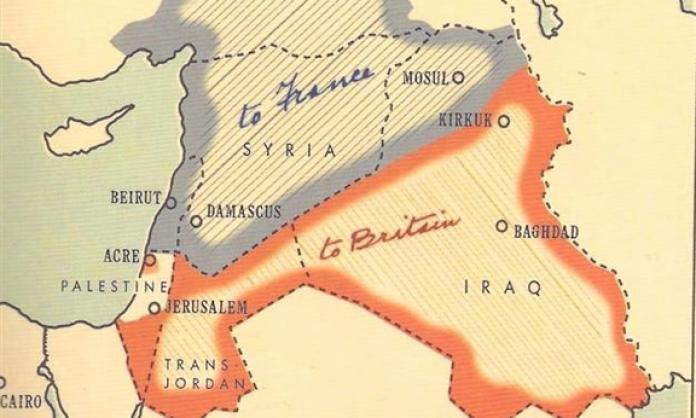

“I should like to draw a line from the ‘e’ in Acre to the last ‘k’ in Kirkuk.” British colonel Mark Sykes was stooped, finger poised, over a map of the Middle East. Over his shoulder stood French diplomat François Georges-Picot. The year was 1915. They were discussing a secret agreement that would divide the Middle East between the Western powers. By the end of the meeting, the contours of the next century’s imperial battles had been drawn.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement was signed the following year and finessed over the subsequent decade. It constructed the modern Middle East out of the detritus of the Ottoman Empire. Parts of Syria and the bulk of what is now Lebanon came under French control; Britain took southern and central Mesopotamia (present day Iraq). Palestine was governed by an international administration. The rest of Syria, northern Iraq and Jordan gained nominal Arab leaderships – but in reality they were under the thumb of imperial powers.

Sykes-Picot created countries where there had been none, establishing imperial European domination and fostering divisions among the indigenous populations. A British finger tracing a line across a map shaped the lives and fates of millions of people yet to be born.

Imperialism, lies and double-dealing

As European capitalism expanded in the latter part of the 19th century, the major powers began to scramble for control of the rest of the world. They ransacked entire continents for their resources, enslaved populations and created enclaves under their domination. Old empires had to be defeated and new ones forged.

The Middle East became central to this process. Not only is it oil rich, but the region is also one of the most important bridges for trade between Western Europe and Asia. Control over these trading routes was vital to all European powers and the Ottoman Empire, and when diplomatic skirmishes couldn’t solve the inevitable impasses, military conflict took their place.

World War One broke out as a result of the heightened competition between the major capitalist powers. But even within the power blocs that formed during the war, there were tensions and rivalries.

Marx described the ruling class as a “band of warring brothers”. So it was. Britain and France were allies by day, but competitors by night. While Britain was negotiating with the French over the division of the Middle East, it was simultaneously horse trading with various Arab dynasties and the developing Zionist movement. Promises were made and rapidly broken.

The British brokered a deal with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, a self-appointed representative of various Arab nationalities. Hussein was prepared to lead a force against the Ottomans in exchange for the promise of a substantial kingdom after the war. The British readily acceded, accepting the military personnel while promising land that they had already promised to others.

Similar double-dealing was going on with and within the Zionist movement. James Barr, author of A line in the sand, notes: “No sooner than Sykes and Georges-Picot had cooked up this deal the British started thinking about how they might get around it. The British had been wondering about how they might use Zionism – the political campaign to get a Jewish state in Palestine – in their own interest”.

The Zionist movement was a minority of the Jewish population at the time of World War One, but it was gathering force. Its goal was to establish a Jewish homeland, which would give the aspiring Zionist leaders their own state to rule. Having neither guns nor the diplomatic clout to pursue their interests, the Zionists appealed to the imperial powers. They met with the Russians, the Germans, the French and the British.

The British were most open to their proposals. They could see the advantage in building up a colonial population, consisting mainly of European Jews, in the strategic area of Palestine. This population would be thankful for and dependent on the British, and prepared to act in their interests if any threat to their regional dominance emerged. In 1917, the British signed the Balfour Declaration, which indicated their intention to support the establishment of a Zionist state in Palestine.

A spanner in the works

The tsarist Russian Empire had been participating in negotiations over the distribution of territory after the eventual break-up of the Ottoman Empire. But the 1917 Bolshevik-led workers’ revolution threw a spanner in the works. The revolutionary soviet government had a policy of publishing all secret diplomatic documents. It was the early 20th century equivalent of WikiLeaks.

The policy was an attempt to show the workers of the world how little the ruling classes cared for the lives and aspirations of their subjects. It also had the effect of revealing the duplicity of the Entente leaders.

The Zionists thought that too many promises had been made to the Arab rulers and that the British wouldn’t follow through on the Balfour pledge. Eventually, Palestine became a British protectorate – a situation not entirely welcomed by the Zionists and forcefully rejected by the Palestinians.

The Palestinians waged regular and fierce battles against both the British and the Zionist forces from the 1920s through to the establishment of Israel in 1948. Extreme hubris reigned in the chambers of Europe’s imperial rulers. They simply had not accounted for the will of the local populations.

Not only did the rich and powerful Arabs of the region feel slighted by the European imperialists, but the Arab masses had desired genuine independence and were enraged by the British and French betrayal. Fire was added to the fury of the nationalist movements that would develop in the subsequent decades.

In Syria, there was trouble from the beginning of the French mandate in 1919. The potentate, Sharif Faisal, looked like he might start ruling in his own interests, so the French immediately dethroned him.

In Mesopotamia, the British faced a huge local revolt. Syria and parts of Lebanon erupted in major conflagrations in 1925-26. Further waves of nationalist rebellion swept the region after World War Two, and a variety of pan-Arab movements attempted to redraw the map in the late 1950s and early 1960s. By this time, the British and French empires had significantly declined, and anti-colonial movements managed to establish new locally ruled states.

The leaders of the anti-colonial forces quickly became capitalist rulers in their own right, and many of them created brutal regimes of terror over their own populations: the Baathists in Iraq and Syria are a case in point.

During the Cold War, the rivalry between Russia and the US often played out in the Middle East. When the USSR fell, the US remained the dominant Western force in the region, corralling, controlling and collaborating with various butchers and beasts to establish a free-flowing, pro-US capitalism.

When its control was challenged, it brought death and destruction. Such a situation not only benefited the US but also massively enriched a tiny local parasitic minority across the region.

The Arab Spring and the counter-revolution

In 2011, the cauldron of class tensions and hostility to repressive dictatorships exploded into the Arab Spring. Dictators fell as millions of workers and the oppressed hit the squares and the streets, went on strike, burned down police stations and stormed government buildings.

The political situation was transformed. The masses had, to use the Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky’s words, “forcibly entered the realm of history”. The modern Middle East as envisaged by two rigid old colonialists in 1916 now looked like it was being born anew. All the old certainties, all the old borders and boundaries, all the longstanding enmities and sectarian divisions were thrown into the air.

CNN journalist Ben Wedeman described the following experience in February 2011:

“‘Your passports please’, said the young man in civilian clothing toting an AK-47 at the Libyan border. ‘For what?’ responded our driver, Saleh, a burly, bearded man who had picked us up just moments before. ‘There is no government. What is the point?’ He pulled away with a dismissive laugh. On the Libyan side, there were no officials, no passport control, no customs.”

For a brief period, it looked like the situation in the Middle East might be permanently transformed. But the capitalist order was never going to crumble without concerted resistance. The forces of reaction fought back.

In Egypt, the deep state stepped out of the dark with general al-Sisi at its head. The regime is in the process of attempting to crush, not only the rapidly compromising Muslim Brotherhood, but the left and the workers’ movement.

In Bahrain, the regime beheaded the movement, murdering or jailing activists and freedom fighters in their thousands. In Syria, the Assad regime has attempted to bury the revolutionary movement under mortar fire and barrel bombs. Whole cities such as Aleppo have been turned into rubble; millions have been displaced and turned into refugees.

From this firestorm of counter-revolution, forces such as ISIS have emerged that want to destroy the old borders and create a new pan-Islamic state. After ISIS swept across Syria and Iraq in 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced, “This blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy”.

Their vision for the destruction of Sykes-Picot is far from the kind the left would desire. The Arab Spring promised a Middle East where the aspirations of the many are prioritised over those of the few, and where the borders that have stoked tension and national rivalries are destroyed by working class solidarity rather than religious enmity.

If the next century is to provide a better life for the people of the Middle East than the last, then it must not be ISIS, but a new mass rebellion by millions of Syrians, Kurds, Iraqis, Lebanese and Egyptians struggling side by side, that erases the maps drawn by Sykes and Picot 100 years ago.