“I reckon it’s never been eradicated, mate … I reckon it’s been a big cover-up, between the government and these companies.” I’m speaking with Dave [not his real name], a coal miner and proud CFMEU member from Moura in central Queensland. We’re talking about the shocking re-emergence on the state’s coalfields of a disease thought long gone – black lung.

In December 2015, Queensland mines minister Anthony Lynham was forced to admit that the incurable and often fatal disease – also known as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis – was back, three decades after government and industry declared it had been wiped out.

In November, three men were diagnosed. At the time of writing, the number of confirmed cases is 14. The miners’ union, the CFMEU, claims to know more than 30 additional victims already. It fears that the number might reach 1,000 before the crisis is over.

Black lung is untreatable. It is also entirely and easily preventable – yet astounding government negligence, combined with the coal companies’ ceaseless drive for profit, has revived a disease many associate with Dickensian England.

At the moment the scandal is centred on Queensland’s mines department. Queensland mines are permitted to operate with higher dust levels than other states, and at twice the level allowed in the US. But despite the risk to workers mining in these conditions, the department’s health screening operations were haphazard and seemingly carried out with a cavalier disinterest in the safety of the workers it was charged with protecting.

By law, mine owners are required routinely to send into the department their workers’ chest X-rays for examination. Some companies never comply with this requirement. There is no evidence that any attempts were made to force compliance.

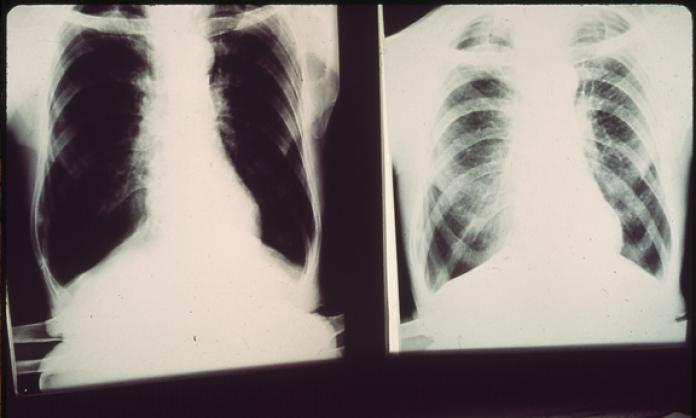

But other companies did send in X-rays, tens of thousands of them. According to CFMEU state mining division president Stephen Smyth, there is an estimated backlog of 80,000 to 100,000 X-rays sitting in the mines department’s Brisbane offices. Some date back decades. The X-rays and associated health assessments are yet to be registered on the department’s database, let alone medically examined.

An independent review of the monitoring and screening system run by the department has found astonishing incompetence and systemic neglect. “Resources to enter data into the database did not increase when the number of health assessments increased during the mining boom”, reported Professor Malcolm Simm, the head of Monash University’s occupational and environmental health division.

The review also found that files are stored across three sites, with no effective system for ensuring that all records for each worker are stored together. Speaking to Medical Republic, a health industry publication, professor Peter Gibson, president of the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, explained that this would make early detection of the disease in workers’ lungs impossible.

“You need to detect very subtle changes and you therefore need to compare things at the moment to what was collected in the past”, he said. “Doctors doing the assessments do not appear to have had access to previous documentation. So it would be impossible for them to detect subtle changes.”

Crucially, the mines department also has no “B readers” – skilled technicians trained to pick up the early warning signs of black lung. Some chest X-rays deemed not to show the disease have now been reassessed in the US, with the disease being identified.

This calamitous system means that miners who have previously received the all-clear may in fact still contract, or already have, the disease. Like Steve Mellor. At 39 he is the youngest man diagnosed with the disease in this recent resurgence. After nine years in the industry, his recently revised records show that he developed black lung in just his second or third year on the job.

But even a short chat with Dave makes clear that the problem extends much further than the state government and deep into the practices of mine managers and the powerful Queensland resources industry.

To get a better handle on the situation underground, I also talk to Ross, who worked at Middlemount in Queensland for several years. I ask if he is surprised by the news that black lung is back. He laughs and says no.

“Carl, fair dinkum mate, if you went on holidays, it’d take you two weeks before you’d stop blowing black snot, and [for] the coal to stop coming out of your eyes and your ears …. You used to always be able to tell underground miners: they’d be fuckin’ black under the eyes like eye shadow and black under the nose.”

“If you want to make an underground coal mine safe, you’re making it unprofitable. I mean, they’re just a dangerous fuckin’ place.”

Over the years, advances in technology – and, more importantly, hard-fought battles by workers to unionise and win safer working conditions – have reduced the number of workers dying in catastrophic mine disasters like explosions and cave-ins.

But if coal mines are not properly ventilated and watered to keep the dust down, if dust levels are not regularly measured, if workers are not equipped with appropriate protective equipment and if their lungs are not routinely X-rayed to detect the early signs of the disease – then inhaled coal dust can slowly build up to the point where it permanently scars their lungs (fibrosis) or gradually kills the lung tissue (necrosis). The effects range from shortness of breath to permanent need for a respirator to breathe, and eventually death.

In Australia, there is no national standard for recording and controlling dust levels. In Queensland, the industry self-regulates dust monitoring in the mines. Mines minister Lynham admitted in January that eight of Queensland’s 14 underground coal mines had been operating with dust levels above legal limits.

According to Ross, it’s the day-to-day shortcuts and oversights of management that lead to overexposure to dust. He’s convinced that if they really had their hearts in keeping dust levels down, they could do it. “It’s not easy but it’s not hard … they’d just have to increase ventilation.

“When you’re in the main ventilation shaft, it’s all good. But when you go off into the side sections where the ventilation isn’t so good, that’s where you’ll get the dust and all that crap.”

Dave agrees. The mine in Moura where he works is open cut. Above-ground miners are not protected from permanent lung damage caused by dust particles. In fact, they also face the danger of silicosis, a disease similar to black lung, but caused by exposure to silica, which comes from the rock that open cut miners drill through.

Many workers at Moura drive enclosed vehicles. Contrary to comments in the Brisbane Times recently from Queensland Resources Council chief executive Michael Roche – whose truck driving credentials are yet to be confirmed by Red Flag – that open cut miners “are not running around open-cut mines exposed to dust”, Dave says that coal dust often gets into their cabs. It would take only basic maintenance to ensure their safety, but that would cost money and time, neither of which mine owners are disposed to spend on anything other than coal production.

“I’ve told them they need to upgrade all the door rubbers … and make sure all the cabin pressurisers are working, instead of half dodgying them up and half making them work. We’ve got water trucks [to keep down dust on the roads], but a lot of them are broken down sometimes, and the truckies keep driving in the dust all the time.” Despite being in the front line of danger, Dave’s biggest worry is about the community in the townships around the mine.

“The worst thing with these mines is … like fair enough, we work in it every day of the week. But mate, we’ve got winds here that blow dust all over these towns, day in, day out. What about the kids? I know Moura’s pretty bad with asthma. But it’s only because of the dust out of the mine. Have any of the kids been checked?”

It’s a frightening question, but neither of us knows the answer. I ask Dave about his own health. How often has he been X-rayed? I’m stunned to find out that open cut workers aren’t required by law to be tested. The union is fighting to change this.

“I’ve been in the industry nearly 20 years and I’ve been done twice … [one] in 2002 and I got one done about three weeks ago.”

I ask him if he got the all clear. There’s a long silence.

“I still haven’t asked for the results. You don’t want that burden over your head, you know? For them to say ‘You’ve got black lung’. I’ve got a wife and two kids, they’re 12 and 9.

“Mate, there’s a lot of blokes like me, I’m telling you. They don’t want to know.”

The sombre mood is broken when Dave talks about what the union has been doing.

“We’ve been doing lots of campaigns. We did marches in front of parliament house, in Brisbane … there was about 20 of us from Moura that went.”

I ask him if industrial activity is on the cards. Dave hasn’t been on strike in about 10 years, but he reckons there’s never been a better time for it. He’s spoken to a few others at his work, and heard murmurings from a neighbouring union lodge.

“Yeah mate, let’s just walk out. Give them a week straight up, just to think about things. Pull the whole lot of us out, the whole lot of Queensland.”

Here’s hoping they fight and win. I’m heartened by Dave’s keen sense of justice. He tells me about the string of disasters in Moura which led to the end of underground mining there. The last was in 1994, when an explosion took the lives of 11 miners. The bodies of those men remained entombed in the sealed mine.

“After them disasters in Moura, mate, none of them managers got jailed either. If we don’t start putting some of these blokes behind bars – which they need doing – they’re going to keep going.”

The CFMEU is continuing to fight for stricter monitoring and controls on dust levels inside mines; qualified B readers in the mines department; the clearing of the current backlog of X-rays; and the extension of screenings to retrenched and retired workers and the broader community in mining towns. More information can be found at the CFMEU’s campaign website www.dusttodust.org.au.