When Victorians look back on 2016, they will remember the year for two things: the premiership win of perennial football underdogs Western Bulldogs, and the United Firefighters’ Union’s attempt to take over the Country Fire Authority. One was a complete fairy tale, and the other a game of footy.

The flare-up of the CFA dispute is an extraordinary episode in Victoria’s recent political history. It created, by a long distance, the deepest crisis to have confronted Daniel Andrews and the state Labor government he leads. It handed Malcolm Turnbull a major political victory at a time when his victories were rare, and pressure was mounting on his do-nothing leadership style.

The dispute has been a gift to drama-mongering newspaper editors and histrionic conservatives alike. Of the 50 shades of mania driving the public narrative, Derryn Hinch’s description of the Victorian premier as an “out-of-control arsonist” sits near the rational end of the spectrum.

The Herald Sun, desperately trying to foment some type of bush “mutiny”, made multiple declarations of “war” across its front pages. A hastily convened Senate enquiry heard from a panicked volunteer firefighter who pleaded for federal intervention because the dispute, he claimed, was like “bringing back apartheid”.

But it was a post-election appearance by federal employment minister Michaelia Cash on Sky News at which peak hysteria was reached. “This fight is their Ash Wednesday”, she said of the CFA campaign against the union, in an interview with Sky’s political editor David Speers.

Her likening of the dispute to the 1983 bushfires that killed 75 – including a crew of 12 volunteers who were trapped inside their truck when it was consumed by flames – wasn’t an ill-considered overstatement. Far from it. The minister carefully repeated her comparison, more slowly for better effect the second time. “This fight is their Ash Wednesday.”

Despite (or because of) the saturation level coverage of the dispute in the Victorian media during periods of the year, the facts of this dispute have generally been obscured or distorted. What is it about a single industrial campaign involving around 900 workers in one corner of the country that precipitated a hostile intervention from the federal government and brought a state government to the brink of implosion?

A sketch of the dispute

Members of the United Firefighters’ Union started negotiating with the CFA for a new enterprise agreement in the months before the September 2013 expiry of their existing deal. At the time, Liberal premier Denis Napthine headed the Victorian state government.

While the CFA had no intention of conceding to its workers, because it is a statutory authority, it was the government of the day that had the last word on negotiations. The Liberal government was in no rush to sign on to a new deal with unionised firefighters, and talks stalled.

The firies weren’t the only public sector workers having their wage claims frustrated by the government. By the time the 2014 state election rolled around, there were large numbers of disgruntled, well-organised and well-liked groups of workers with a very particular interest in seeing the back of the Liberal government. The Labor opposition blew a few kisses in their direction, the unions took their cue and, in an election-shifting tactic, mobilised an army of firies, paramedics and nurses to campaign against the Liberals.

The culmination of then opposition leader Daniel Andrews’ pre-election courtship of the firefighters was an address to a large union-organised meeting at the Collingwood Town Hall. He vowed to “end the war against them”, bring their dispute to an end and to fund 450 additional firefighters – 350 of them for the CFA. He was greeted by a standing ovation.

Daniel Andrews won office in November 2014. His televised election night victory speech included a pointed acknowledgment of the role the unions and their members played in getting him there. That was more than two years ago.

Patently, the war against firefighters did not end with Labor’s ascendancy to government. Deals were quickly and quietly locked away with the nurses and the paramedics, but the firefighters were left out in the cold. Jane Garrett, the responsible minister, steadfastly backed the CFA board’s refusal to sign a deal, describing the union’s log of claims as “outrageous”.

Said to have been a rising star in Labor’s left faction, Garrett walked away from any assurances given to the firefighters who traipsed around her inner-city electorate of Brunswick to campaign for her in a tightly run race against the Greens.

Throughout 2015, relations between the union and government continued to sour, and progress on an agreement halted. The union launched a public campaign against Daniel Andrews’ broken promises. In December of that year, speaking to Red Flag at a rally against the government, Steve, a firefighter said: “We campaigned for them … we believed that they were going to be different, they have changed from being our friend to now being our adversary”.

As 2015 drew to a close, looking for a way out, the government sought the intervention of the Fair Work Commission. In June, in the middle of the federal election campaign, the commission handed down its recommendations for settlement and came down largely on the side of the union. The CFA was apoplectic.

The deal, it claimed, would hand operational control of the organisation to the union and devastate the state’s thousands of CFA volunteers. Writing in the Herald Sun, Jeff Kennett described the proposed agreement as “an attack on the very fabric of our being”. Kennett’s statement was characteristically hyperbolic, but he was swimming with a huge and deranged tide of reactionary sentiment.

The decision of the “independent umpire”, though, offered the government a path to end the conflict while avoiding the appearance that it had caved into what the media labelled as “excessive union demands”. But Garrett and the CFA board refused to budge and instead fortified their positions. The government was wedged and pressure mounted.

The Murdoch press – followed dutifully by Fairfax – then kicked off a frenzied campaign against the union, waged firefighters and the government. For 19 days in the month of June, coverage of the “union takeover” was stamped across the front page of the Herald Sun. The newspaper distributed “Back the CFA” bumper stickers by the tens of thousands.

The state Liberal party launched a front group – Hands off the CFA – which produced placards and leaflets for volunteer brigades. It was campaign that was gift wrapped for delivery to the federal party. According to a report on Crikey, News Corp reporters on the federal election campaign trail were instructed to ask Bill Shorten daily about the dispute.

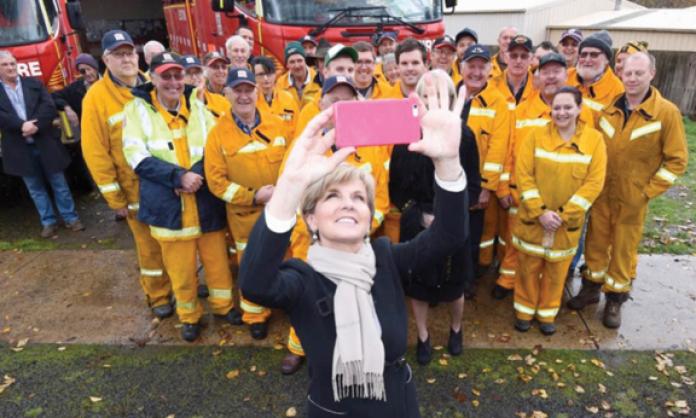

Before the month was out, the stand-off with Garrett had ended with her resignation from cabinet, the entire CFA board had been sacked, and Malcolm-Money Bags-Turnbull was marching around the Victorian bush addressing rallies of angry volunteers and pledging to protect them from union control if returned to government.

At its core, this is an ordinary industrial dispute. The firefighters did what thousands of groups of workers across the country do every year. They drafted a log of claims. They bargained with the boss through their union and aimed to have the claims they could win reflected in a legally binding agreement that set their wages and conditions. Their demands were typical: a wage increase, various entitlements, safety standards, consultation about equipment and protective clothing and conditions such as minimum numbers at fires.

This is the basic grind of Australia’s industrial relations system. It’s a bit of push and shove carried out within narrow legal parameters that are monitored by the Fair Work Commission. Annually, the commission approves an average of 6,500 such collective agreements.

Of the thousands of agreements churned through the system each year, rarely would one make the news. Rarer still are claims of a “union takeover”. Yet, every one of the thousands of agreements on the books is a product of the very same fight playing out between career firefighters and the CFA – a struggle for control.

When and how workers do their job; how many breaks they take; what entitlements they receive; how much they are paid; whether they work weekends, evenings; what equipment they use and the clothes they wear – these are questions of control. On a daily basis, these are the small battlegrounds over which workers and bosses fight in workplaces across the country. This is class struggle at its most basic. It’s why workers get organised. It’s what keeps union officials in a job.

The CFA though is no ordinary employer. If an organisation could be said to have a mindset, the CFA’s would be described as suspicious and defensive. It is obsessively hierarchical and has carefully sought to replicate a military-like organisational structure. Control, for the CFA, is not a managerial aspiration; it is a reason for being.

Like any boss, the management of the CFA aims to wrest more control than it hands over to organised workers. But the protection of managerial prerogative is not a cause to which employers have ever succeeded in rallying public support. Reframing the dispute as being between unions thugs and hero volunteers ensured that the CFA could wage a proxy war for its managerial prerogative through its volunteer base.

The CFA had good reason to assume that it would find support among the volunteers. This is a social force ripe for mobilisation against a union cause – farmers and rural business owners. Though they are of course not a singular bloc, what is known about the social group that Turnbull describes as the “very best of us” points to the sensibleness of the CFA strategy.

A rare CFA survey, taken from a sample of brigades in 2007, found that a quarter of volunteers live on a farm, and nearly half are business owners (compared with 15 percent in the rest of the population). Again, nearly half work in the agriculture, forestry and fishing industry (compared with 3 percent of the rest of the population). While it would be expected that some in this number are workers, not farmers or business owners, the agriculture, forestry and fishing industry is one of the most poorly unionised sections of the workforce (3 percent compared to the average across all industries and sectors). It is reasonable to guess that class consciousness does not run high among many workers who volunteer in the CFA.

The CFA – behind the myth

Today, the CFA has around 1,200 brigades across rural and regional Victoria and a wide suburban ring taking in major population and industrial centres such as Frankston, Dandenong, Melton and Cranbourne. According to the CFA’s own figures, about 98 percent of its brigades are solely volunteer-based. There are 32 CFA stations that are staffed by paid firefighters and volunteers – the so-called “integrated stations”. These stations are located in the regional and suburban centres which fall within the CFA catchment.

The organisation claims 55,000 volunteers (35,000 of them operational), and about 2,400 paid staff (about 900 operational). According to its reports, around a third of paid CFA staff also serve as volunteers.

The reality, if not the rhetoric, of the CFA is that it is an overwhelmingly urban organisation. To take the last figures readily available, in 2010, nearly 75 percent of the 27,000 odd incidents to which CFA crews responded were what the CFA classified as “urban incidents”. The same year’s figures also show that more than half of CFA brigades “turned out” fewer than 10 times a year. In any given year between 30-40 percent of CFA volunteers will not “turn out” even once.

Taken together, the figures paint a very different picture to the “bush spirit” image publicly stoked by the organisation. The CFA’s integrated stations form its highly active urban centre. Though a fraction of the total brigade numbers, they are responsible for most of what the organisation does. Then, there is the numerical majority, the volunteer-only country and bush brigades which are isolated and largely not active, or only occasionally so.

The design of the CFA is the legacy of more than a century of empire building and sectional agitation between insurance companies, municipal councils, farmers and business owners. The history of the development of the fire services in Victoria is long, complex and riddled with fierce rivalries. It is marked by unending contestation about the composition of the services. From the beginning, furious disputes have been waged about who pays and how, whether firefighters are waged or volunteer and who fights which fires where.

The goal has always been a service that protects the relevant economic interests while creating the smallest possible financial impost on the owners of those interests. Throughout that history, the use of volunteers has been a key battle fought among rural communities, the union and the CFA. The honourable and courageous volunteer butting up against the mercenary waged firefighter is a trope with a long back story. It was studiously rolled out again in this dispute.

It was in 1854, at a meeting in the Victorian town of Geelong, that an American, J.R. Bailey, started the process that ended nearly a century later in the establishment of this firefighting icon of the Australian bush spirit. In recognition of the risk to the town of fire and the apparent “paucity of means” possessed by the insurance companies to prevent the damage, Bailey moved for the creation of a volunteer fire brigade in Geelong.

“It behoved the public to take the initial step”, his motion argued, “and then they could go to the government with a good grace and ask them to purchase the necessary equipment”. The Geelong volunteer brigade was made up of local traders and merchants, according to Robert Murray and Kate White’s definitive history of volunteer firefighting in Victoria, State of Fire. Over the next 40 years volunteer brigades – formed with varying degrees of enthusiasm – sprang up in gold field towns and then farming communities around the state.

In Melbourne, a mid-century building boom was growing the city at a rapid rate. Firefighting services, however, were rudimentary and chaotic. Insurance brigades were dominant but had limited effectiveness, fought each other bitterly and were despatched only to fires affecting buildings with insurance. In the outer metropolitan area, where insured buildings were few, dozens of volunteer brigades formed. Businesses also created “volunteer” brigades from their workforce.

In 1890, the basic division that exists still today was established. There would be a Metropolitan Fire Brigade Board to oversee firefighting within 16 kilometres of the city centre. Volunteer metropolitan brigades were disbanded and volunteers offered employment in a new waged-only service. The rest – or more specifically the rest of the state that anybody cared to protect – fell to the newly created Country Fire Brigades Board – a volunteer-based body. “Volunteers” in these brigades were mostly business and land owners, and often their employees. Their concern was fire control in towns. Their business was not bushfires.

After a time, wealthy holiday makers decided that someone ought also to volunteer to preserve their favourite bush retreats. The Melbourne Volunteer Bush Fire Brigade was formed at a meeting in the city called by Nationalist Party (later Liberal Party) parliamentarian H.S Gullett. The bush brigades were created to “protect from the ravages of summer fires the beautiful holiday and recreation areas” of the state. Until then, according to Murray and White’s account, forest fires were controlled by forest commission workers who commandeered and paid wages to timber workers, farm labourers and townspeople when they needed extra hands.

Funding was never willingly given by insurers, governments or councils, and conditions for both groups of firefighters were poor. However, the rivalry between the country and bush brigades was intense. Relations between the two didn’t soften until years after they were joined in 1945, when the Country Fire Authority was born. By then, the UFU presented as a mutual enemy that rural and bush brigades could unite against.

After the war, the CFA endeavoured to fill its officer ranks with returned servicemen and establish a regimented organisational structure. But the union was making important industrial advances for the small number of paid firefighters in the service. This did not sit well with the military-style aspiration of the CFA.

When, in 1969, after years of trying, the UFU won federal registration as a union, the CFA had the decision reversed in a High Court challenge. When the union fought for a federal award to set conditions for waged firefighters across the country, the CFA led the battle against it on behalf of all fire services in the country.

The CFA’s fight against the union has never been limited to the wages for paid firefighters. It has mounted its forces against every attempt to gain additional paid firefighting resources for the country and outer suburban areas. A now infamous example played out during the deadly Ash Wednesday fires, when the CFA refused the assistance of taskforces of off-duty MFB firefighters to help beat back the out-of-control blaze. Historically, as today, it has been the union which has forced the establishment of basic safety standards and extracted money for improved equipment for volunteers and waged firefighters alike.

What now?

The end of this dispute is not anywhere in sight. Turnbull’s first legislative victory after the federal election was to amend the Fair Work Act “to protect” the CFA volunteers. It was a strictly political manouvere. Legal commentators have roundly described the changes as confused. There are debates about whether they are constitutionally valid.

It’s not yet clear what impact, if any, the new laws will have on the proposed enterprise agreement at the heart of this fight. What is clear, however, is that the most dangerous legacy of this dispute is organisational not legal.

The CFA dispute is the first time in a long time that the right has successfully tapped into and cohered a mass force around its virulently anti-worker agenda. Try as they have to nourish it, conservatives have not been able to foster a broad anti-union sentiment in Australia. This dispute provides them with a blueprint for success and an identifies a clear base from which they can build.

For our side, the dispute is a warning. As if fighting a bushfire with a garden hose, the union movement, the left and the state Labor government proved powerless to dampen the reactionary hellfire that for a few weeks entirely engulfed the state. We will need to do a better job next time.