Over the last few weeks, hundreds of thousands of students walked onto university campuses for the first time. They were met with banners, websites and presentations welcoming them to august public institutions where collaboration and reasoned discussion are key.

But contrary to their marketing material, universities are captive to the same profit motive and grubby managerialism as private business. While increasing fees for students and awarding themselves salaries averaging more than $800,000 per year, Australia’s university vice-chancellors are busy driving down the pay and conditions of their employees.

Vice-chancellors across the country are currently in negotiations with the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) for new enterprise agreements that set employment conditions at each university. On the cards for academics is a ramping up of “productivity” – longer teaching hours and pressure to meet increasing research output targets. Non-academic staff face having their conditions reduced to the level of non-union private sector workers.

At the forefront of this offensive is Murdoch University in WA. Led by vice-chancellor Eeva Leinonen, Murdoch applied to the Fair Work Commission in December to terminate the existing enterprise agreement covering staff. If the university wins the case, it will be able to put all of its employees on minimum award conditions.

A statement issued by NTEU general secretary Graeme McCulloch highlights how much is at stake: “[M]anagement, if it chooses, [will have] the capacity to demolish working conditions including the possibility of reducing wages by 25 to 39 percent; cutting redundancy entitlements by one third for academics and 80 percent for professional staff; removing all academic workload regulation; ending rights to academic and intellectual freedom; and eliminating employer provided parental leave”.

While Leinonen has used shock and awe, other vice-chancellors are trying to win hearts and minds to get through the same agenda. At Deakin and Melbourne universities, management released entirely new “agreements” accompanied by a slick marketing campaign before even beginning negotiations with the union.

At Deakin the proposed agreement would increase academic teaching loads by 80 percent – requiring academic staff to teach every trimester while removing a number of workload protections. Melbourne University is dividing academic and general staff by having two separate agreements. The general staff agreement replaces pay increments based upon time of service with “performance pay”. A competitive performance pay scheme will divide workers, exacerbate gender pay inequity and drive down wages overall.

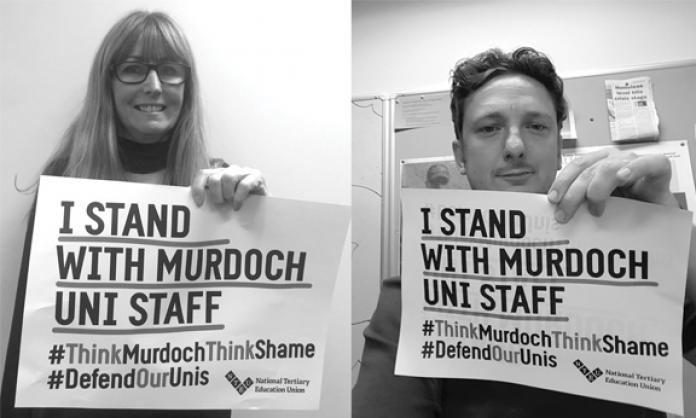

These attacks have shaken up union members but have not yet stirred serious discussion about mounting an industrial fight-back. To date the NTEU has relied upon arguments at the bargaining table, legal action, public relations and social media campaigns to respond to the management offensive. But in spite of legal action and a nationwide campaign of letter writing by union members, Leinonen has not backed down. Other vice-chancellors are drawing confidence from this.

Vice-chancellors have no reason to take the NTEU seriously at the bargaining table unless the union can credibly threaten serious and effective industrial action by members. Nothing short of a sustained campaign of strikes, pickets and protests on campuses across the country will achieve this. Building such a campaign is no small task, but it is possible.

The Murdoch NTEU branch called its first strike in years in December. Despite its being held just weeks before Christmas and with relatively little building work, there was an overwhelming response from members. Initially called as a half-day stoppage, the protest escalated into a 24-hour strike with 100 union members standing on picket lines. As a one-off action, this strike alone cannot win the campaign. But there is recent history of university staff taking things further and winning.

In 2013, the Sydney University NTEU branch beat back major attacks and won gains through a sustained campaign of industrial action. This involved a wide layer of union members building a series of strike days. The strikes combined traditional industrial tactics – stop-works, picket lines and IT workers shutting down networks – with support from student activists who roamed around campus disrupting and shutting down classes. The combined efforts of staff and students turned the campus into a ghost town at the height of semester – a major humiliation for the university.

While other campuses have not pulled off actions like that at Sydney University, now is as good a time as any to try. Millions around the world, including thousands of university staff and students in Australia, are currently engaged in protests against Donald Trump. The power of collective action is being demonstrated by a movement that has put the world’s most powerful and arrogant man on the back foot. Knowing this, NTEU members should go out with confidence that we can recruit to the union, strike and beat the shabby little autocrats who run our universities.