To be a radical in Australia today, one must confront a daunting reality. To transform society, we must overcome powerful institutions designed to hold back social change. To do so, we need a mass socialist movement, harnessing our collective power to a project of fundamental social change.

But in most of the world, socialist ideas are marginal to politics; apathy reigns. Many people are dissatisfied with their life, or with society, in one way or another. But few are motivated to do anything about it.

Mainstream political pundits often complain of voter apathy. But activist apathy is the bigger problem. Only 11 percent of Australians have attended a protest in the last three years. And strikes – when activism invades and transforms the workplace, disrupting the very engine-room of capitalism – are rare.

While our side may be passive and disengaged right now, the capitalist class is always carrying out plans to confuse and demoralise the oppressed. Schools teach respect for authority and competition with other students. The realities of working life make many fearful of defying the boss. The capitalist press lies with impunity to promote fear, prejudice and self-doubt.

Disengagement, hopelessness and political conservatism go hand in hand. How can we fight for each other’s rights, when we are often unable to defend our own?

It is natural in such circumstances that people will, to a greater or lesser extent, accept the ideas and prejudices that bombard them every day from the capitalist institutions.

Human nature to blame?

We are sometimes told that racism comes from an ingrained human fear of the “other”, that sexist behaviour is “hard-wired” and inescapable and that people are naturally inclined to individualistic self-interest at the expense of others.

None of these explanations are true. Human beings have only recently come to exhibit the behaviours now upheld as natural and eternal; only 500 years ago, this continent was inhabited by people with an entirely different way of life and, with it, an entirely different set of values, behaviours and norms.

The simplest explanation comes from Karl Marx, who said that “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas”. In our epoch, those ideas – that oppression and discrimination are natural, that war is noble, that workers must accept their subjection – dominate. They can’t completely overwhelm us: for example, 74 percent of Australians believe that big business has too much power, and 55 percent believe that wealth ought to be redistributed. But few believe the claims of socialists that workers can run the world and create a classless society.

Most of us draw our sense of what’s possible from our daily lives – where we experience constant powerlessness – and from the “experts” who reinforce every argument that, one way or another, “mob rule” (i.e. democracy) equals chaos. The ideas of the ruling class dominate simply because of the awesome power of our oppressors: the power of their institutions and their power over our lives.

Radical change is possible

It can be tempting to retreat inward: to focus on perfecting our own private lives, to live and consume ethically, to find a middle class not-for-profit job in which one can do good and get paid for it.

All these solutions amount to accepting the individualism and powerlessness that we are taught from birth, but putting a quasi-radical spin on it. No “ethical” job or “radical” jargon can ever challenge the rule of a class that lives and profits from poverty, oppression, war and social chaos. It is unsurprising that these non-solutions are encouraged with such fervour at capitalist universities – but they offer no way out.

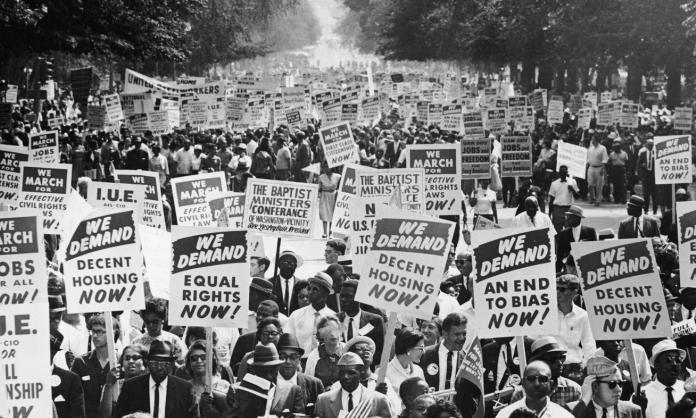

Instead, we must remember how rapidly things can change. Consider the United States in the 1950s: a time of frenzied anti-Communist witch-hunting, when any sympathiser of the left was driven from public life with blackmail and persecution; when Jim Crow segregation reigned throughout the South; and when the individualist ideology of capitalism appeared to have suffocated any hope of a challenge.

And then consider the same United States in the late 1960s: the land of Black Power and the Black Panthers; riots and uprisings in major cities across the country; a revived revolutionary socialist movement; and the world-shaking movement against the Vietnam War. It was the same country, with the same social system. But the ideas and behaviours of millions had changed: they had become radicalised.

How does this change come about, and where does it lead? Capitalism lays the basis for it, with its recurrent crises. They can take many forms: a war, an economic crash, a breakdown of political institutions and more. The atrocity of imperialist war brought about the global radicalisation of the 1960s, and the Russian revolution 50 years earlier. Economic and political crises brought about the 2011 Arab revolutions and Occupy movement in countries previously characterised by years of relative political calm. The very insanity of capitalism – built into the foundations of the system – is its own undoing.

Struggle changes people

Crisis does not guarantee the emergence of a new radical politics. This happens only if the oppressed begin to take collective action against their own oppression. In the process of fighting for our basic rights – whether it is the right not to starve, the right to vote or the right not to be killed in war – we are all forced to confront immediate practical questions, which raise enormous political questions.

How can we encourage more to join us? How do we organise? How can we overcome attacks from the police and the courts? Who are our real allies and who are our enemies? Can our problems be satisfied with a new government – or do we need more fundamental change? If a radical change is needed, how can it be accomplished?

All these questions confront any great social movement. And those who take part in it – although they may initially be unaware of broader political questions, uninterested in theory or motivated by narrow concerns – must consider their answers carefully. This is why protests and social movements are so important to revolutionaries. In them, people can learn more in a month than they can in a lifetime of passivity.

“The real education of the masses can never be separated from their independent political and especially revolutionary struggle”, wrote the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin. “Only struggle educates the exploited class.”

Marxists often reduce this insight to two crucial words: struggle educates.

For the working class, struggle can educate us to do more. Workers’ struggle relies on strength in numbers: a strike, unlike a protest, can only be truly effective if a majority of workers take part. For this reason, solidarity is the watchword of workers in struggle. And effective solidarity must transcend boundaries of nation, race, sex and sexuality. Effective struggle requires and teaches us to overcome our prejudices – and vice versa. That is why the trade unions with the best experience of fighting for wages and conditions are also those that have the proudest history of fighting for political and social justice.

From resistance to revolution

Workers’ struggle also relies on organisation. If strikes spread, for example, they have to be coordinated to ensure that we all stay on strike, or go back to work, together. The class has to have consistent demands and coordinated decision making. In mass strikes and great struggles, the working class invented institutions known as workers’ councils, in which its tremendous power to reshape society was given authority.

No workers’ council will be constituted by an act of parliament, because the existence of such councils threatens capitalist rule. They can be built only from the education provided by struggle. Councils of workers provide our class with an experience totally unlike our day-to-day lives under capitalism: the experience of exploited people learning to reorganise society collectively. Russian Marxists were among the first to recognise this as the best path beyond capitalism, and to call for such councils to take power. When apathy breaks down in a crisis, it can point towards workers’ power – and revolution.

“Revolution is necessary”, wrote Karl Marx, “not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew”.

The muck of ages is the filth we are taught by our existence as oppressed people in a class society. It is the muck of racism, sexism, nationalism and war. But it is also the muck of apathy, of misery, and the belief that we must be ruled by others, that elites must exist and human desire and potential must be restrained. It is our training to obey the dictates of the system.

There is no guarantee that a crisis will end in us cleansing ourselves of the muck of ages and creating a new world. Many times, crisis just causes more misery.

That is why it is vital for those who want to see a better world to organise now, so that we can help turn anger into resistance, fight alongside those learning in struggle, build stronger organisations, prove in action that a better world is possible and prepare for the struggles to come.