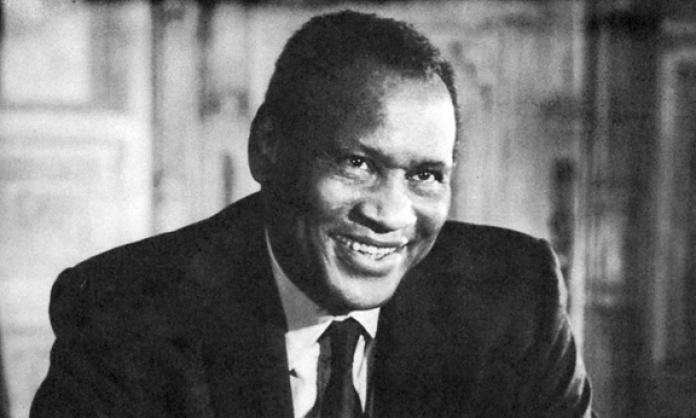

On 12 June 1956, Paul Robeson faced the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) as part of an investigation into the use of passports “in the furtherance of the objectives of the Communist conspiracy”. Things did not go quite as the committee intended.

In round after round of “verbal fencing”, Robeson not only refused to answer questions, but also countered the attacks of chairman Francis E. Walter, an “overt white supremacist”.

At the peak of the confrontation, Walter asked Robeson why he didn’t leave the US and go live in Russia. As Jeff Sparrow recounts in No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson, the world-famous performer responded with “one of the most ringing answers given to interrogators” throughout HUAC’s campaign:

“‘Because my father was a slave’, Paul said, ‘and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?’”

It was. So clear that Walter moved to adjourn, muttering, “I’ve endured all of this that I can”. Robeson won that verbal battle, but years of confinement, denial of a passport and being “locked inside a nation that considered him a traitor and a threat” took their toll. It would be two more years before the Supreme Court ruled that “the secretary of state could not deny a passport on the basis of a citizen’s political beliefs”.

No Way But This traces the milestones of Robeson’s extraordinary life, beginning with his rise from obscurity as the son of a former slave to become a prize-winning scholar and football star, then to global fame as a renowned singer and actor. Sparrow also charts the development of Robeson’s political consciousness and activism – from his early awareness and anger at the racism that permeated every aspect of his life in the US, to his embrace of radical left politics and working class solidarity.

Retracing Robeson’s footsteps through North Carolina and Harlem, the theatres of London where Robeson performed Othello to standing ovations, the mining villages of Wales, the battlegrounds of Spain, the relics of Stalin’s Russia and even the scaffolding of the Sydney Opera House, Sparrow meets a cast of real-life characters who keep the memory of Robeson alive and calls forth the ghost of the man himself.

The effect of this hybrid storytelling is remarkably intimate and revealing. “Paul”, as Sparrow refers to Robeson, becomes much more than just a hidden, half-forgotten figure of history. Instead, his defining characteristics of determination, commitment, compassion and defiance start to make this character appear as flesh and blood – someone we urgently need to know, a man whose principles and actions resonate today as we face the immediate challenges of standing up to racism and reaction everywhere.

Sparrow writes of Robeson’s support for the Welsh labour movement after a chance encounter with protesting miners from the Rhondda Valley (solidarity that would later be reciprocated by thousands of miners when Robeson’s US passport was cancelled), as well as his support for the civil rights movement and the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War.

Sparrow also refutes some of the criticism of Robeson’s wife Essie, who is sometimes painted as “ruthless, grasping and ambitious”. He points out that “Essie’s steel would be a key factor in Paul’s success”; that she refused, when hauled before McCarthy’s committee, to disavow either Robeson or the left wing causes they both supported; and that Essie, while “not militant by temperament”, was so deeply affected by what she saw when travelling with Robeson through war-torn Spain that “she identified wholly with the Spanish cause”.

In the final chapters, Sparrow deals with Robeson’s decline into physical and mental illness, and his dogged refusal to recognise the Soviet Union as anything but a “land free of prejudice and exploitation”. Partly, Sparrow explains, Robeson’s own experience of visiting the USSR shaped his attitude: “In Moscow he’d first walked in human dignity; in Moscow, he’d been persuaded racism could be abolished”. (He remained oblivious to Stalin’s brutal repression of ethnic minorities.)

But Robeson’s intransigence was also fuelled by his determination not to “besmirch the vision that had inspired him and all the people like him – the conviction that a better society was an immediate possibility”. The tragedy of Robeson’s personal decline and his disastrous refusal to acknowledge the crimes of the USSR do not, as Sparrow argues, negate his achievements or his political courage at other turning points in his life.

Perhaps the moment in No Way But This that best illuminates Robeson’s spirit and character is Sparrow’s description of the archival video footage of Robeson’s impromptu performance of “Ol’ Man River” (with his own, defiant revisions to the lyrics) to Sydney Opera House construction workers in 1960.

“In 1960, construction workers were not respectable. Concert halls did not cater to labourers, whom few considered deserving of fine music or sophisticated entertainments … [B]y transforming – if only for a lunch hour – their worksite into the musical venue it would eventually become, Robeson makes a statement characteristic of his life and career. You aren’t, he says to them, simply tools for others; you’re not beasts, suitable only for hoisting and carrying, even if that’s the role you’ve been allotted. You’re entitled to culture, to music and art and all of life’s good things – and one day you shall have them.

“By the time the last resonant notes have died away, some of those on the scaffolding are weeping.”

Robeson’s character, art, principled politics and legacy of extraordinary courage all come vividly to life in No Way But This. There are many worthy books about the life of Paul Robeson, but this is one not to be missed.