On 14 August 1917, readers of the Sydney Morning Herald were treated to the following passage by Mr W.D. Carmalt, the manager of the refreshment rooms at Central Station. He was relating the scandalous behaviour of the young women whom he employed as waitresses:

“For the past few days the girls had been rather out of hand. They were inclined to laugh and jeer at those over them, and discipline was being seriously affected. Acting under instructions, I called them all together this morning. I explained to them that they were there in the public interest, to serve anyone who should come along. [They had refused to serve some scabs.] I then asked those who were willing to abide by that course to stand to one side, and those that were prepared to leave to do so. Thereupon they all put on their hats and coats and marched off, amidst laughter and cheers.”

The behaviour of these young women may have scandalised their manager and the respectable middle class readers of the Herald. It was, however, typical of the behaviour of many workers in Sydney in August 1917. Beginning in the railway workshops of Eveleigh and Randwick, a mass strike had spread through Sydney and the industrial centres of NSW. Within weeks, Melbourne was in its grip and the strike would involve, in the end, workers in every state.

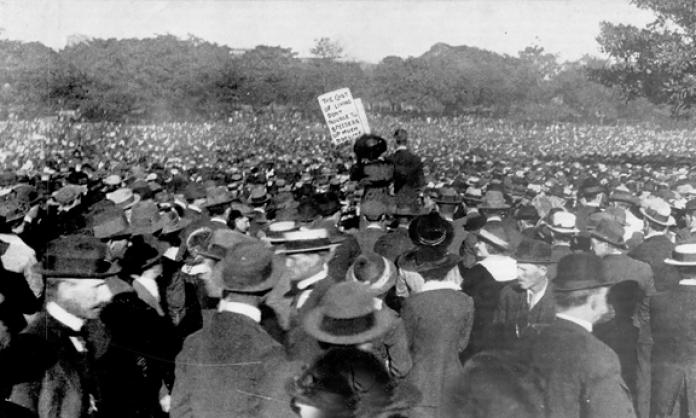

At its height, in late August and early September, 100,000 were on strike. There were daily demonstrations of thousands in Sydney, reaching tens of thousands on Sundays (around 150,000 on one occasion) and 30,000 marched on the federal Parliament in Melbourne under the leadership of Adela Pankhurst of the Victorian Socialist Party. As Pankhurst and her followers battled police in Bourke Street, a panicked backbencher asked the relevant minister whether it was true that the great Irish trade unionist, James Larkin, was on his way to Sydney from San Francisco. Unfortunately the rumour was untrue, but the parliamentarian’s fear is still palpable, even when expressed in the musty pages of old Hansard.

The MP may have had in mind Larkin’s brother Peter, recently jailed along with 11 other leaders of the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World, accused of attempting to burn down commercial buildings in Sydney. The IWW was being crushed by state repression as the strike unfolded, but that didn’t stop the crowds from singing what the Sydney Morning Herald described as a “labour song to the tune of John Brown’s Body”. The song was, of course, the IWW anthem, “Solidarity forever”, penned in the US in 1916 and introduced to Australia by the IWW Song Book.

What were they striking over? For decades, historians have struggled to explain how a strike over a relatively obscure workplace issue in one workplace in Sydney – the introduction of time cards to monitor the work of skilled workers in the railway workshops – could provoke such an explosion of solidarity. The introduction of time cards was a genuine attack, but that doesn’t explain why, to tackle some obvious examples, the waitresses at Central Station or the teenage employees of a soap factory in South Melbourne went on strike.

The best way to understand this strike is through the prism of Rosa Luxembourg’s classic analysis of the mass strikes that occurred in the build-up to the 1905 Russian revolution, and, in particular, how economic and political issues intertwined and alternated as motives for mass action.

The First World War was wreaking havoc on Australian society in 1917. More than 1 percent of the Australian population died in the war, 10,000 alone in the muddy chaos of Passchendaele, which coincided with the strike. The economic impact of the war was almost as great: real wages fell by a staggering 30 percent between 1914 and 1919. Add the political impact of the revolt in Ireland on a country in which 20 percent of the population were Irish Catholic and the result was a profound political crisis.

A strike wave had begun in response to this crisis in early 1916, and in that year 1 million workers went on strike, mostly successfully. Even the police in Melbourne had unionised, after a secret meeting organised by Irish Catholic policemen held in the Women Peace Army’s Guild Hall (in the same month as an IWW meeting on Ireland had been scheduled in the same venue – cancelled by the arrest of the main speaker, Peter Larkin).

The attack on the railway workers was itself caused by the war – the NSW railways had been built with borrowed money, and a wartime surge in interest rates placed the service in debt. The strike began as a rank and file revolt – there were no union officials present at the meeting that voted to strike – and it spread in the same manner. One by one, groups of workers joined in rather than being seen to cooperate with scab labour. It spread first to the rest of the railway service, though a third, mostly in rural areas of NSW, remained at work.

The key was when the coal miners joined in. Coal fuelled the industrial economy – like oil today. Being asked to handle coal that might have been hewed or transported by scabs was the excuse to strike – for wharfies and seamen up and down the east coast, for carters and drivers working the waterfronts of Sydney and Melbourne and for workers in a range of factories in Melbourne and Sydney.

When, in late August, a group of union officials were arrested for conspiracy to start a strike they had actually done their best to stop, the Broken Hill miners joined the strike. They had won a strike in 1916 and, as they produced most of the lead used for munitions by the Allies, the government had made sure it had massive stockpiles of lead ore.

But the ore had to be smelted in Port Pirie, and a strike at the smelter was narrowly averted when the skilled unions enforced a secret ballot. The wharfies at Port Pirie, however, refused to unload coal for the smelter and, despite their union threatening them with expulsion and the government decreeing Port Pirie a military zone and organising shipments by rail from Port Lincoln, the smelter nearly ran out of coal, which would have deprived the Allied war machine of a critical raw material.

The Wonthaggi coal miners, who supplied a third of the coal for the Victorian Railways, also joined in protest at the arrests. The Victorian Railways, unlike their NSW counterparts, had no great stocks of coal in reserve and were afraid to use NSW coal for fear of provoking a walkout by Victorian railway workers. To keep the state operating, Victoria was forced to introduce tight rationing; thousands of workers were laid off. In September, in Melbourne’s streets, darkened by the absence of lighting, men and women, who had turned out to defend Adela Pankhurst’s right to free speech, rioted, smashing the windows of shops and of factories such as Dunlop in Port Melbourne, which were running with scab labour.

For all of this enthusiasm, however, the strike had a core weakness. One-third of the NSW railway workforce never joined the strike, and both federal and state governments mobilised on an unprecedented scale to defeat it. In the context of war, scabbing was portrayed as a patriotic duty, and, in addition to the usual desperate men who could be persuaded to betray their class for an income, an army of “volunteers” from the middle class and from rural areas was recruited. They were put up at the SCG and later, to the amusement of many, at Taronga Zoo.

The universities and the elite private schools in Melbourne and Sydney provided recruits. There were even attempts to get some of the private school boys to operate a coal mine in the Hunter Valley, though they weren’t that successful in mining any coal.

The rural recruits, however, possessed more skills. Farmers’ sons could unload a ship, or drive a horse and cart to and from the docks. Typical was a stock and station agent, and nephew of a conservative member of parliament, who shot dead a picketing worker while driving a cart from the Sydney waterfront. He was acquitted eventually, and left to the Mitchell Library a scrapbook full of letters of support from his middle class admirers. Typical is a letter from a headmaster in Sydney who believed he had been “too lenient”. Another anonymous admirer from Melbourne complained: “What with that damned Mannix [archbishop of Melbourne and opponent of the war], and a judge giving preference to unionists, we might as well give the country back to the blacks”.

A more serious problem with the strike was the nature of its leadership. Most of the striking workers walked out without an official call but, once having done so, left the conduct of the strike to officials who were at best reluctant, and in many cases determined to end the strike at the first opportunity. Picketing was for the most part discouraged, though there were random acts of violence such as sabotage of railway lines, and one scab engineer was shot while driving a train through the mining district north of Wollongong. A clumsy attempt to frame two miners for this (the police claimed to have found incriminating bullets wrapped in an IWW song sheet in a search of one of their homes) collapsed when it was proved they were in Sydney at the time of the shooting.

No attempt was made to spread the strike to strategically vulnerable areas. And at the first opportunity, on 9 September 1917, the Defence Committee (the body of officials charged with leading the strike) called it off on terms that amounted to total capitulation. The Herald described the reaction of the strikers to the news:

“A huge crowd of men assembled shortly after 1 o’clock yesterday [Sunday, 10 September] outside the Trades Hall and carried a resolution, ‘That the workers and the trades unions of this country have no more confidence in the strike executive’. The gathering arose in extraordinary circumstances. One of the men was writing in chalk, in large block letters, on the wall of the building, an announcement of a mass meeting to be held in the Domain on the following afternoon, at 3 o’clock. Of the big crowd around him – it was growing in force every minute – some protested. ‘Let it be this afternoon’, they cried. It was this incident which gave rise to the further proceedings.

“It was stated in the course of speeches that the men were on the eve of a great victory, and if the trades unionists remained stalwart they would win. ‘Another fortnight’, said one speaker, ‘and we have got them. Are we going back?’ (‘No.’) … The crowd was so great that it spread itself along Goulburn-street practically from Sussex-street to the Trades Hall. A number of men, headed by one of the union banners, pushed their way through the crowd, and the men who were assembled were urged by one and another to join the procession and proceed to the Domain in order to discuss the position further.”

Mass meeting after mass meeting rejected the sell-out, but the officials refused to accept this. The result was a messy return to work as the less militant used the official position as an excuse to return. Eventually, as the militants were isolated, they were forced to accept defeat, and after two weeks the strike was over. Except, that is, for those workers who had been replaced by scabs. Two of the biggest pits in the Hunter were staffed entirely by scabs recruited in rural Victoria, and the rest of the field held out for a month in solidarity with their displaced comrades. The waterfronts of Sydney and Melbourne were also flooded with scabs who had set up scab unions. The wharfies were faced with the bitter choice of remaining on strike rather than accept standing in line behind scabs every day at the pick-up. When the Melbourne men returned in December, the strike was finally over.

Billy Hughes was emboldened by this major defeat of the trade unions (and by the crushing of the IWW) to call a second conscription referendum, but its defeat was the first indication that the government’s victory was not as straightforward as it might have thought. It would learn in the next 18 months how rapidly a seeming victory in the class war can be turned around.

As coal miners returned from fighting on the Western Front, some of them found themselves working beside scabs in the Hunter Valley pits. It’s dark down a coal mine, and after 12 months, the Hunter was free of scabs. A campaign of intimidation, which involved, among other things, returned servicemen throwing scabs into the Yarra, eventually cleared the Melbourne waterfront of scabs as well.

The most spectacular example was Fremantle, where a strike in 1917 had been broken, borrowing the tactics adopted in the eastern states and a scab union set up. Here an alliance of wharfies and returned soldiers confronted 800 bayonet-wielding police. The police killed one wharfie, but when the officer in charge noticed how many of the diggers had armed themselves, he began to have second thoughts. As it happened, at that moment a troopship arrived and a semaphore from the returned men was answered with an offer of armed assistance from the troops. It wasn’t needed, as the police beat a hasty retreat and wouldn’t return to Fremantle for another three months.

In 1919, there was the biggest wave of strikes in Australia’s history, spearheaded by groups who had all shared in the defeat of 1917: the coal miners, the Broken Hill miners and the seamen. The latter had reacted to the defeat by replacing their right wing officials with a team headed by Tom Walsh, a founding member of the Communist Party. The only significant group not to share in this quick revival was the one group of workers who hadn’t struck uniformly – the NSW railway workers, though even there the association of men who never scabbed (the “lillywhites”) was at the core of a more prolonged fight to re-establish a fighting union.

The Great Strike was a product of the most severe crisis yet faced by Australian capitalism, a combination of a devastating imperial war and an economic crisis that slashed the living standards of the working class by a third. It helped solidify a layer of militant workers with an attraction to revolutionary politics that would, for a time, be cohered organisationally in the form of the Communist Party.

As well as its historic significance, the strike is also a classic example of how it is usually better to fight and lose than to submit.