For decades, the people of Yemen have suffered the moral and material indignities of foreign intervention, elite corruption and the social and economic underdevelopment that comes with them. Even before the conflict escalated to its current state, Yemen was the poorest country in the Middle East. In 2014, it ranked lower per capita than Palestine and Syria on a purchasing price adjusted basis.

Yemen’s people have long relied on remittances from migrant workers in the Gulf and south Asian regions. Yet even this meagre source of funding dried up as the Saudis imposed a strangling blockade on the country.

There are numerous reports of desperately needed medical supplies being held up for months outside Yemeni ports, even after the UN has certified that they contain no weapons. Many others are never allowed through the blockade.

Up to 7 million people are at risk of starving, the World Food Organisation estimating that 150,000 children may die of malnourishment in the next few months. Compounding this disaster is the fastest growing cholera epidemic in history, which UN sources believe has infected almost 1 million people.

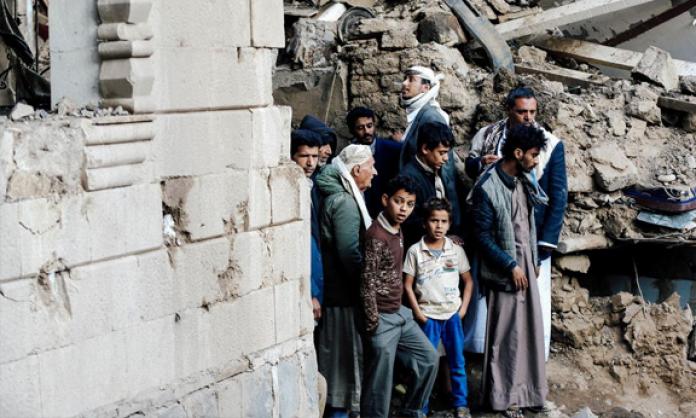

Meanwhile, the military onslaught continues. Saudi Arabia has dropped thousands of bombs on the impoverished nation, decimating what little infrastructure and industry existed. In the south, ground troops funded and backed by the United Arab Emirates continue their attacks on Houthi, al-Qaeda and civilian targets.

Building an anti-war consciousness – and hopefully a movement – against this largely invisible war is a challenge. But it is also an absolute duty.

This is especially the case in the West, which is deeply involved in the conflict both officially and unofficially. When the Saudis began open warfare in March 2015, the British government backed it enthusiastically, no doubt driven in part by the $1 billion in arms sales announced immediately afterwards. Predictably, this weaponry has been used on Yemeni civilians, including cluster bombs banned by the UN.

Trump is even more passionate about his love for the Saudi war machine. Earlier this year, he signed off on a weapons deal he claimed was worth US$110 billion, with another $240 billion to come over the next decade. As part of its broad logistical support for the war, the US has provided in-flight refuelling to Saudi warplanes, allowing them to extend the reach of their destructive bombing.

While Australian foreign minister Julie Bishop has been more measured, guided by Australia’s relatively close relationship with Iran, she nonetheless provided an implied defence one month after the war began, citing “president Hadi’s request for protection and the military action taken in response by Saudi Arabia”.

Australian ex-soldiers and generals have played a substantial role as mercenaries on the Saudi side of the conflict, a fact that has received no critical attention in the mainstream media, in contrast to the enormous coverage given those joining other militias in the Middle East. Australia has also imposed sanctions on Yemen, contributing to the humanitarian catastrophe.

We must demand an immediate end to the war on Yemen, an investigation into war crimes committed or supported by the West and its allies and massive reparations to put the country on its feet. Without this support, it is difficult to see how Yemen will recover from the barbarity inflicted on it by the Saudis and their cynical supporters in the US and Australian ruling classes.