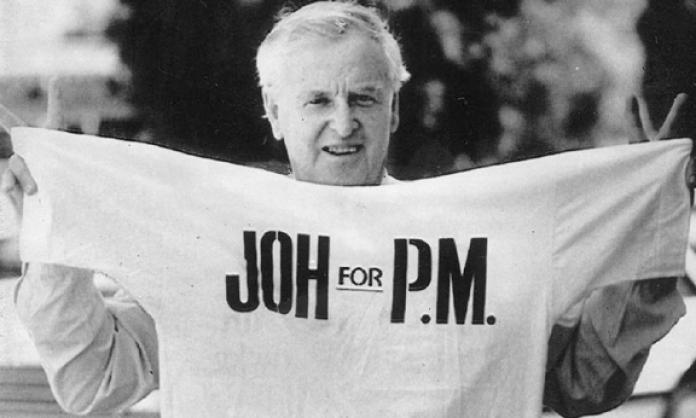

Queensland is considered more conservative and backward than the southern states. Queensland “difference” has been used to explain the long period of conservative National Party rule from the 1950s under the extreme right wing premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, the foul Liberal National Party Islamophobe George Christensen and the careers of populists like Bob Katter and Clive Palmer.

While there is nothing uniquely Queensland about racist and conservative politics in Australia, Queensland is different. It is a state with distinct political traditions flowing from its unique history of economic development.

A key consequence of a regionalised and decentralised economy with low rates of industrialisation has been a weaker Queensland capitalist class. For most of the 20th century, interstate and foreign companies dominated the state’s economy. With less of a big local capitalist class to drive investment and economic expansion, governance and state politics were concerned to promote capitalist development.

Today this impulse is expressed in the slavish and bipartisan commitment to the mining sector and paving the way for corporations like Adani to establish their operations in the state.

Not only this, but the centrality of Queensland’s primary industries and the regionalist nature of its economic development also provided part of the historic basis for intense and enduring racism, with state-sponsored clearing of Aboriginal land, first for grazing and later for large scale mining projects requiring the most vile and brutal dispossession and genocide.

Queensland’s economic development also shaped the establishment parties and politics in marked ways. The regional cities grew up initially around ports to service the primary industries. Cities like Cairns, Townsville and Mackay became the centre of Queensland politics and economy, overshadowing Brisbane.

Despite the capital being larger than any single regional city, Brisbane never became the place where most of the state’s population lived, and it is still the case that most of Queensland’s population, some 51 percent, lives outside it. By comparison, 65 percent of the NSW population lives in greater Sydney, and Melbourne is home to 76 percent of Victoria’s population.

State government policy was written in Brisbane, but with a focus on regional development. This explains why the Country/National parties historically have been stronger than the Liberals in Queensland. It also helps to explain how the Labor Party developed more country, populist sensibilities than its southern equivalents. Its early base was among seasonal and itinerant shearers, meatworkers, sugar workers and transport, port and railways workers, but also among small farmers in the sugar industry.

The working class was not only more regional but also less industrialised, and therefore more monocultural than the southern states, where manufacturing led to higher concentrations of migrant workers. The labour movement was also dominated by the Australian Workers Union, with a union leadership that favoured arbitration over strikes and was preoccupied to keep Labor in government.

Yet concentrations of regional workers, far from Brisbane and the reach of AWU officialdom and parliamentarians, and under the influence of syndicalism and the Industrial Workers of the World, set the scene for vibrant outbreaks of militant trade unionism and resistance, earning the state the moniker of “the Red North” by World War One and bringing workers into conflict with state Labor governments that ruled virtually uninterrupted from 1915 to 1957.

At one time, it would have been laughable to suggest that Queensland workers were conservative, loyal nationalists. Queensland was dubbed a site of “latent rebellion” and Bolshevism by prime minster Hughes, who had been pelted with eggs by workers during his 1917 pro-conscription tour of Queensland.

In the 1930s, Communist Party militants led explosive strikes among AWU-organised sugar workers, which united white and southern European migrant workers. In 1944, Fred Paterson, Australia’s only ever Communist MP, was elected to the seat of Bowen, between Mackay and Townsville.

The regionalised nature of Queensland’s economic development can explain seeming contradictions in the history of state politics – the radical working class traditions alongside a state labour movement dominated by a conservative ALP-AWU alliance, for example.

Another contradiction is that between the longest period of continuous Labor government in Australia into the 1950s, followed by a long period of Country/National Party government, made notorious by Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s social conservatism, concessions to big mining corporations, racism and assaults on land rights and civil liberties.

Since the 1970s, and especially in the last few decades, there have been important economic developments that reshaped electoral politics. The once thriving regional centres are in decline, the long term result of changes to agriculture, of mechanisation and modern mining techniques requiring fewer permanent workers.

These shifts, along with the rise of south-east Queensland, tourism and the Brisbane services sector, have undermined the regional cities, eroding public services and infrastructure. Politicians have campaigned on these themes, which has helped drive a right wing populist vote in former National Party strongholds.

Despite these evolutions, the characteristics that gave Queensland its distinctive political character have to a significant extent endured from colonisation to the present. Regionalism over time helped lay the basis for a more populist ALP, and later consolidated the Nationals’ dominance.

Added to this, Queensland has a long history of racism, derived from voracious measures to clear the land for primary industry, which dominated the economy from colonisation, and a working class that, despite its impressive capacity for militancy and radical political traditions, has been fragmented and has suffered from its decentralised and regional nature.

These factors have laid the basis for more conservative, yet volatile, state politics.