The ALP narrowly retained office in the recent Queensland election after saying it would veto Adani’s application for a Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF) loan of $1 billion to construct a rail line from its port in Bowen to the Galilee Basin.

Many believed that the giant Adani coal mine proposal was finished and that the ALP is opposed to it or any other mine in the Galilee Basin.

It’s not true.

The Adani Carmichael mine project has secured a 60-year free endless groundwater agreement from the state government. If operational, the mine would draw more than 12,000 megalitres of groundwater from the Great Artesian Basin every year – 40 percent of the artesian water used for irrigation in Queensland. And a deal approved by the state cabinet in May will deliver infrastructure funding and a royalty holiday for Adani, worth close to $500 million.

Despite the company’s apparent financial squeeze, the environmental and corporate vandal is yet to sell any of its assets, such as the Adani Abbot Point Coal Terminal port just north of Bowen, to keep afloat the prospective mine.

While premier Annastacia Palaszczuk vetoed Adani’s application for a NAIF loan, her cabinet is still considering an application from Aurizon, a commercial rail company, for a similar project to open up the Galilee Basin and enable Adani and other companies with leases in the region, such as Gina Rinehart’s GVK Hancock and Clive Palmer’s Waratah Coal, to operate with even fewer risks and overheads.

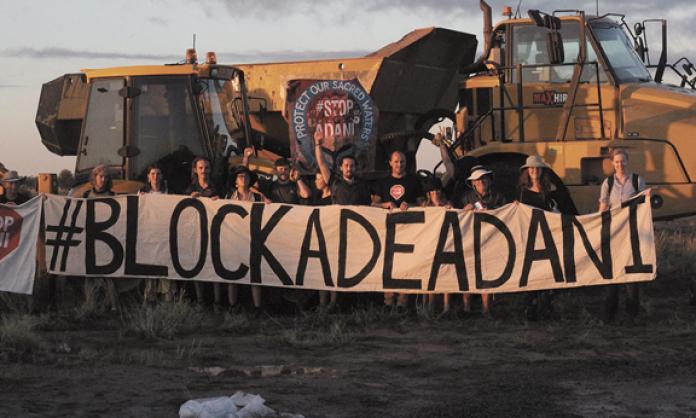

This is why Frontline Action on Coal started 2018 with actions targeting not only Adani, but also Aurizon and the Queensland Labor government. The campaign has continued in the face of intense media and government hysteria.

On 7 January, ALP councillor for the Whitsundays Mike Brunker told the media that protesters “are going to get a clipping”. The Murdoch media also published the address of the camp, and the address of one of the protest leaders, in what appeared an incitement for people to take matters into their own hands against peaceful protesters.

The responses are a testament to the effectiveness and seriousness of FLAC’s actions against Adani and Aurizon. As one camp attendee, Phillip from Melbourne tells Red Flag, “It sounds like that’s bad, but it shows that they’re obviously scared of what we’re doing [and] perceive us as effective”.

The camp

The camp is operated and maintained collectively, and everyone is encouraged to participate in various aspects of its running. Daily agendas are organised through general meetings, and an extensive array of groups allocated tasks organising the camp, ranging from preparations for actions to maintenance of the camp’s amenities.

The camp is well developed, with an open kitchen, working and media spaces, locations suitable for organising anti-coal actions, gardens and various other amenities required for a long campaign.

“You don’t need to be in some type of exclusive activist club”, says Lilli, a student from Sydney. “There is a lot of community building to be done at the camp itself. If you want to come and support the movement, but you’re not in a position to participate in actions for whatever reason, you can just come and help us build infrastructure to make sure that the camp still runs.”

“It’s my first time up here”, Phillip says. “I’ve done some stuff with Stop Adani and GetUp in Melbourne; we’ve done some protests outside the Commonwealth Bank and Westpac when they were talking about the possibility of funding Adani.”

The camp’s participants have a wide range of experience, from first-time participants to activists with a long history of taking action against fossil fuels. Some activists have participated in other direct action campaigns, including anti-coal campaigns in Newcastle, Bentley and the Laird State Forest of New South Wales, allowing them to draw from their extensive experience to aid in the organisation of the camp.

Tess Newport, a 22-year-old student from Melbourne, has participated in some of the direct actions. “I grew up in a small rural community in Victoria”, she says. “I’ve seen first hand the way in which the mining industry rips off workers, communities and the environment. We don’t want jobs in a dying industry – we need jobs for the future.”

Action

Two activists locked themselves onto a barrel full of concrete placed on the Aurizon railway line. This blocked Aurizon coal trains for close to six hours. “You can write letters forever, but at the end of the day, corporate interests are going to win against writing letters to your MP”, Lilli Barto, one protester involved, says. “That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it, but I think that front line action has a really important role to play in providing that urgency and that kind of acute pressure that campaigns like this really need.”

The protest was timed to coincide with a meeting of the state cabinet as it deliberated on providing a NAIF loan to Aurizon. The Queensland government says that the mine will create jobs, despite Adani’s representative in the Queensland Land Court stating under oath that there will be only 1,464 jobs created through the life of the project.

Lilli’s message to the ALP? “Stop pretending that fossil fuel projects are the only way to create regional jobs. I think the regions deserve to be treated better than that. They don’t deserve to get the shitty jobs just because they’re desperate. They deserve to have jobs that are sustainable, that are going to stick around, and that are investing in industries that are going to grow over time.”

FLAC activists escalated the actions, disrupting both Aurizon and Adani collectively for 15 hours, and held up a coal tanker for half a day.

Five FLAC campaigners shut down the Adani Abbot Point Coal Terminal by pulling the safety cord and locking themselves onto the conveyor belt transporting coal to a freighter ship. Despite howls from Adani’s CEO of operations that the protesters were endangering workers’ lives and engaging in violent behaviour, their actions were peaceful.

The port is heavily automated, and only six or seven workers maintain and operate the machinery. There were no workers in that section of the port.

One activist who locked on is Nic Avery from Sydney. “Because the port is owned by Adani, and because it is such a strategic piece of infrastructure for extraction in the Bowen and Galilee Basin, it is particularly significant that we show that people are prepared to take direct action there”, he says.

“These actions cause very large disruption to Adani’s operations, and are extremely effective in derailing their attempt to profit from environmental destruction. I can only imagine that this sort of thing will continue until mining is ruled out in the Galilee Basin.”

The activists lock on by placing their forearms into large metal cylinders and chaining their hands together inside. It takes police hours to remove each protester.

“To know that we had shut down a process of extraction which stretches hundreds of kilometres into the coal mines in the Bowen Basin was a phenomenal feeling. It’s difficult to express it in words. I won’t lie, though: being locked on was also very difficult, physically uncomfortable and mentally challenging.

“We oppose the government and the coal industry’s joint push to extinguish Indigenous land rights. Adani’s dirty coal project has no consent. The traditional owners have said no, climate scientists have said no, and we are here on the front lines to say no.”

Just as the last protester was taken away by police from Abbot Point at 5:30am, Aurizon received a phone call that another action was in place and they had best shut down the trains again. Natalie Berry, a 20-year-old student from Sydney, was in a cot suspended from a tree, the only rope supporting her tied to the tracks 20 metres below. It wasn’t until mid-afternoon that she was taken down; as the only crew qualified to bring her down safely had to be flown up from Brisbane.

Where to next?

The FLAC camp is determined to continue the fight against any new coal. Anyone interested in attending will find a camp full of people, young and the young-at-heart, new activists and old hands, all dedicated to stopping Adani and doing what they can to prevent further climate change.

One of the significant challenges for the activists directly involved in the protests is fines, which can total several thousand dollars. Those who support the actions of FLAC but cannot attend the camp can find fundraiser pages at Chuffed.org.

As in any significant campaign, protests in the capital cities are also important. The Franklin Dam dispute in 1983 had dozens of people engaging in direct action at the site while thousands of people rallied in Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart.

If we are to put a halt to Adani and any new coal projects, it will take a serious effort by thousands of people across the country prepared to get organised, take action and mobilise. If the passion and determination found at the FLAC camp are anything to go by, we’re well on the way.