Zelda D’Aprano, famous for chaining herself to the railings of the Commonwealth Building in Melbourne in 1969 to demand equal pay for women, died on 21 February, aged 90.

Zelda was born into a working class Jewish family in Carlton in 1928. Following her mother’s example, she became a member of the Communist Party. Initially, she worked in factories and later for the Meat Industry Union.

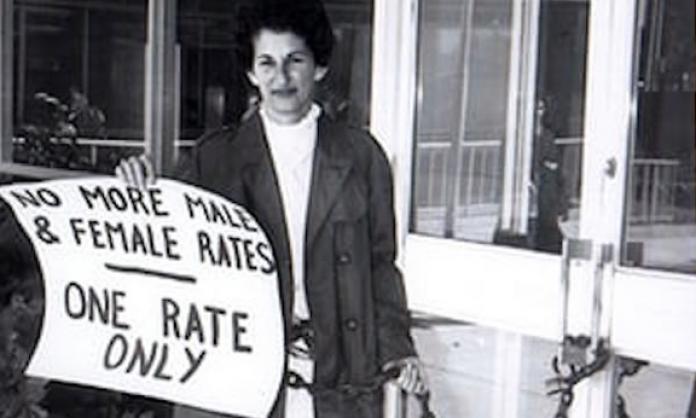

The meat industry was a test case for the equal pay campaign. She and other unionists were present at the Arbitration Commission ruling that the minimum wage would continue to be set at different rates for men and women.

Four male judges decided not to grant “equal pay for work of equal value” but only “equal pay for equal work” to the few women who did the same work as men in male-dominated occupations. Female-dominated industries such as nursing missed out, and only about 5 percent of women got equal pay.

“There we were, the poor women, all sitting in Court like a lot of cows in the sale yards, while all the men out front presented arguments as to how much we were worth”, Zelda later wrote. “I felt humiliated, belittled and degraded, not for myself but for all women.”

So on 21 October 1969, Zelda chained herself to the railing, until she was removed by police. “We decided I would chain myself [there], because the government should set the example. Private industry won’t do anything if the government won’t.”

Zelda’s action occurred against a background of mass mobilisation. In 1968, there was mass action worldwide. In Australia in 1969, strike action defeated the penal powers used against unions for decades. In this context, it is not so surprising that Zelda chose direct action.

Ten days later, on 31 October, she was joined by Alva Geikie and Thelma Solomon. The three women chained themselves across the doors of the Arbitration Court.

The events drew enormous attention to the campaign, and led to Zelda and others establishing a Women’s Action Committee (WAC) in early 1970, a group very important in the lead-up to the emergence of the women’s liberation movement.

“The type of women’s organisation we envisaged was a militant organisation, for we recognised that women were not going to achieve anything unless they were prepared to fight”, Zelda wrote. “We had passed the stage of caring about a ‘lady-like’ image because women had for too long been polite and lady-like and were still being ignored.”

Over the next few years, there were several highly successful WAC protests. In the “equality ride” on a Melbourne tram in 1970, a group of equal pay campaigners, including Zelda and Bon Hull, refused to pay more than 75 percent of the adult tram fare to protest that working women received 75 percent of male wages.

Zelda never had an easy ride. She was always up front, not afraid of conflict or disagreement, and called a spade a spade. She was a thorn in the side of many people.

Recognising the need for a support group during the chaining action, she asked her trade unionist employers at Trades Hall for some women to take an hour off work to be there. They refused.

When she wrote a private letter to one of the Communist leaders of the union that employed her, complaining about how he had snubbed her and other women during a social occasion, she was fired.

She also attracted the attention of ASIO.

By 1971, the features of the new women’s liberation movement were becoming clear. In May, the first trade union-sponsored community consultation on child care was held. In August, the Women’s Action Committee sponsored a national conference on Women in the Workforce and Trade Unions. There was also a demonstration against the Miss Teenage Quest.

A pro-abortion demonstration in Melbourne in November, a brave action as the word “abortion” was almost taboo, attracted 500 people, a significant achievement. But the Melbourne Herald buried it in an inside paragraph with “Dozens of barefoot women took part in an abortion law reform march in the city today”.

Zelda, Thelma, Alva and Bon all enthusiastically joined the women’s liberation movement. Their presence, and that of other older women from the Communist Party and the trade unions, including my mother Rose Stone, helped ensure that the movement had a close relationship with and understanding of working women.

While we did not always see eye to eye politically, I regard Zelda and this generation of militant women activists as inspiring and admirable. With Zelda’s death we are nearing the end of an era. It is very appropriate that Melbourne Trades Hall flew its flag at half mast.