1968 has become known as the year of the student. Across the world, campuses were aflame with political activity. Students challenged university administrations and demanded student control over student life; they railed against racism and inequality in their own countries and fought imperial barbarity in Vietnam.

In some countries, the student movement connected with radicalising workers, and the seemingly stable foundations of capitalist rule were shaken. Regimes and governments, from the openly authoritarian to the nominally democratic, felt under threat and sometimes responded with deadly force.

These experiences led millions of young people across the world to identify as revolutionaries.

University life

The growth in student numbers and the transformation of universities from training grounds for the privileged elite into institutions of mass education created fertile ground for revolt. Young people were being brought together in vast numbers in ways they hadn’t been before. A rebellious youth culture, hostile to the staid conservatism of an older generation, was developing.

The state of the university sector also pushed students along a radical path. Many new universities were created: often bare bones operations, underfunded, sterile and desolate. Poet and participant in the French uprisings Angelo Quattrocchi described Nanterre University in the suburbs of Paris in this way:

“[A]round the campus, still the Arab and Portuguese shantytown … Chimneys, council houses, wasteland. On the walls, written by a spray pistol: URBANITY, CLEANLINESS, SEXUALITY.

“Twelve thousand students. Fifteen hundred live in residence. The rooms are good and sterilized: big glass windows overlooking the Arab barracks. No visits by ‘foreigners’ allowed, you can’t add or change furniture. You cannot cook. No politics on the premises.

“On the external walls: HERE FREEDOM STOPS.”

The new universities trained workers for an evolving economy. While the ideology of the university as an institution of “higher learning” remained, they were increasingly called upon, in the words of Clark Kerr (chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley), to “merge activities with industry as never before”.

This contradiction enraged students across the world. Education should be about more than merely workplace training, it should expand consciousness, they argued. At Hornsey College, England, for instance, students occupied for six weeks against government “reforms” meant to enforce specialisation and academic qualifications on art students.

They took over the administration building and canteen and took on cooking and cleaning responsibilities. They dismantled partitions designed to keep students and staff separate and used general assemblies of hundreds to discuss the daily running of the campus and ways to radically transform education.

One occupier, Val Remy, said: “Nobody told anybody what to do; people discovered talents they’d never known they had. We wanted to prove we could run the college without bureaucratic administration. It was absolutely exhilarating, liberating”.

At the older universities, and in countries where the university system remained antiquated, students pushed against rigid traditionalism. They refused to defer to the authority of the professors. Their iconoclasm knew no bounds.

At Frankfurt University in Germany, radical students became increasingly frustrated with the political quiescence of academics such as leftist social theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. They accused them of being “critical in theory, conformist in practice”.

Students from the revolutionary Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) held “go-ins” at the lectures of politically exposed professors, to challenge them to discussion with the students. At one infamous “go-in”, the lecture theatre seats were strewn with leaflets declaring “Adorno as an institution is dead”.

University administrations, unhappy with the developing radicalism, attempted to ban, expel or otherwise discipline student leaders. This prompted further outrage and increased militancy.

At the London School of Economics, authorities installed steel gates to prevent occupations. In no time, students took to the gates with sledgehammers and picks. One student, Rachel Dyne, recalled: “It was a euphoric feeling, I felt a great sense of power. We were doing something authentic, we resented the gates, felt they were transforming the place more or less into a prison. Taking them down was a way of challenging authority”.

Vietnam

The situation in universities prepared the ground for a radicalisation, but from 1965 in Western Europe, the USA and Australia, the Vietnam war became an increasingly dominant political question for young people.

In the US, the Black and working class populations were against the war from early on. They were the first drafted, the first maimed, the first killed. But while hostility to the war was deep and widespread, the anti-war movement coalesced on campuses.

The ongoing brutality of the war shocked students – strafed villages and cold-blooded murder were caught live on camera. French student Nelly Finkielsztejn captured the moral outrage of the time:

“Napalm, bombings, mass graves, executions – the fury of military and economic might against a small population of a different race – that was the Vietnam war for me. It was intolerable. That’s why we went out into the streets chanting Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Minh!”

During 1968, there were increasingly dramatic student protests against the war. The Tet offensive in January proved that the Vietnamese could breach the defences of the US military. Tet punctured the veneer of US impenetrability and proved to be a lightning rod for students across the world. Tariq Ali, a British Vietnam Solidarity Campaign leader, asked, “If poor peasants could do it, well why not people in Western Europe?”

In February, an International Vietnam Conference was organised in West Berlin. It was attended by 6,000 representatives of international youth groups, along with artists, writers and intellectuals. The hall was decorated with Vietnamese National Liberation Front flags, pictures of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Ernst Thälmann and slogans from Karl Marx, Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh. The mood was electric; 15,000 marched at the conclusion of the conference.

Students supported draft resisters. In Australia, the first national Draft Resisters Conference was held at the La Mama theatre in Carlton in 1968. The conference instituted the first large “Don’t Register” campaign, urging 20-year-old males to refuse to register for national service. This was hugely controversial.

In the USA mass protests regularly shut down draft centres. The US SDS linked up with anti-war soldier organisations and toured members of the Vietnam Veterans against the War around campuses to speak about their experiences.

In Japan, students put their bodies on the line to stop the war. When a US aircraft carrier attempted to dock at the Sasebo Naval Base before heading to South Vietnam, hundreds of students battled police to get into the base to stop it.

Many students tried to connect the war with campus issues. Universities often provided crucial research for war industries; students campaigned to have the universities break links with them. In Britain, one of the most significant occupations of 1968 took place at Essex University after a confrontation between students and a scientist who was complicit in the production of the chemicals being used by the US military.

State reaction and militancy

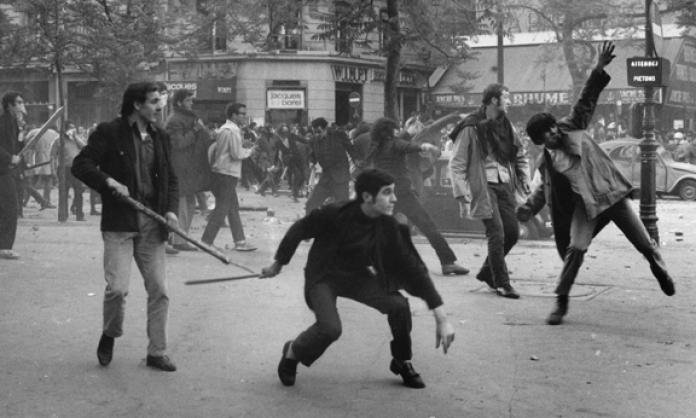

As 1968 wore on and student radicalism deepened, ruling classes became increasingly unsettled. Repression by the police, the universities and the state increased. Fascist violence and right wing vigilantism, often working hand in glove with the authorities, further radicalised many students to the left.

In London, the largest ever anti-Vietnam-war protest was viciously attacked. In Chicago, demonstrations against the Democratic Party convention provoked the Democratic mayor to crack down. One participant, Josh Brown, described events:

“I saw a cop hit a guy over the head and the club break. I turned to my left and saw another cop jab a guy right in the kidneys. And then I turned round and the cop behind me was saying ‘Move, move!’ and I took off and kept going.”

But he found that all the exits and bridges were cut off by National Guardsmen and police. Students were kettled, and in the glare of television lights pummelled, beaten and broken.

After Martin Luther King was killed in April, 174 American cities were engulfed in rage and fire. German student leader Rudi Dutschke was shot by a right wing vigilante in the same month. Tens of thousands of students attacked the headquarters of the right wing publisher Springer Press. They built barricades, set fire to buildings and began, in the words of some student activists, “preparing for civil war”.

In Mexico, authorities were concerned about student rebellion during the Olympic Games and tried to close the vast and radical Autonomous University. Enraged students rebelled and massed in their thousands throughout the city.

On 2 October, a student rally at a central plaza was surrounded by military troops, some carrying machine guns. As students tried to escape, the military opened fire. To this day, the government has refused to release the number of people killed – estimates range from 50 to 500.

The violence awakened students to the underlying brutality of the system. Many drew revolutionary conclusions and realised that, on their own, students could effect minimal change.

Workers and students

The events of France in May 1968 had an impact across the world. That militant student struggle connected with a general strike and brought a conservative government to its knees, transforming the consciousness of many students.

Two days of students battling the police on the streets of Paris prompted workers at a small aviation factory in Nantes, western France, to go on strike. They locked the factory managers in their offices. Three days later, 2 million workers were out all over France; another three days, 9 million.

The largest strike in French history had begun. Workers at industrial plants occupied factories or joined public demonstrations. Millions of French workers joined the actions. Sometimes, the occupations became more radical. Revolutionary students went to the striking enterprises and engaged workers in debate and discussion. Despite the hostility of the conservative trade unions, workers were open to discussions with radical students.

The workers’ actions – the crippling effect that the strike had on the French economy – won students to a world view with the working class at its centre. Nelly Finkielszetjn described it like this:

“The unthinkable had happened! The strikes were like a flame, like everything we had been saying at Nanterre. ‘Fuck hierarchy, authority, this society with its cold, rational, elitist logic! Fuck all the petty bosses and mandarins at the top! Fuck this immutable society that refuses to consider the misery, poverty, inequality and injustice it creates, that divides people according to their origins and skills!’ I had never dreamt such a thing could happen …

“Suddenly they realised that they had to find a new sort of solidarity. That was what was important about May. Not the slogans like ‘Imagination Is Seizing Power’ and the rest, not the poetry and exuberance, but this new found solidarity. That was what May meant to me.”

Many thousands of students across the world were inspired by these events. They hoped for, and sometimes agitated for, a working class response to inequality.

For millions of students, 1968 was a seminal year. Not only were the iniquities of capitalism increasingly exposed, but victorious resistance seemed possible. Thousands of students felt the same as Mike Wallace from Columbia University, who said:

“The usual rules of the game in capitalist society had been set aside. It was phenomenally liberating … At the same time it was a political struggle. It wasn’t just Columbia. There was a fucking war on in Vietnam, and the civil rights movement. These were profound forces that transcend that moment. 1968 cracked the universe open for me. And the fact of getting involved meant that never again was I going to look at something outside with the kind of reflex condemnation or fear. Yes, it was the making of me – or the unmaking.”

It was truly a time of universes cracking open, of tectonic plates shifting and of horizons expanding.