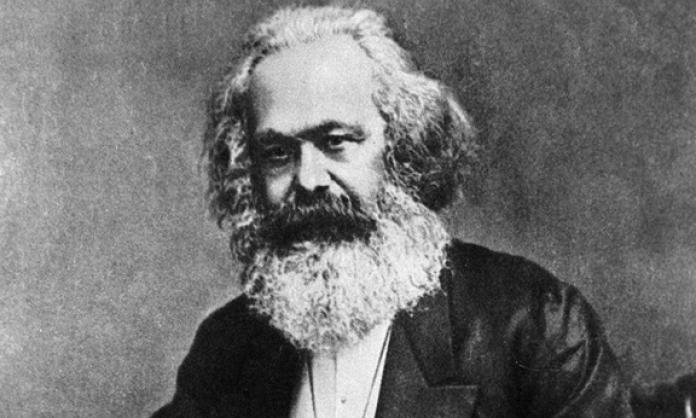

On 5 May 1818, Karl Marx was born into a world on the cusp of a great social transformation.

As he and his lifelong political partner and friend Frederick Engels wrote in the Communist Manifesto in 1848: “The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together”.

If anything, these words undersold the changes that capitalism was only beginning to bring into the world in the first decades of Marx’s life.

When Marx was a child, most of the mechanical energy for a predominantly agricultural society was still provided by oxen, horses and human beings themselves.

Over the course of successive generations to come, the steam engine bound whole continents together by rail, the gasoline combustion engine broke down the divide between urban and rural, and nuclear fuel supplied electricity to hundreds of millions – while nuclear weapons threatened the annihilation of the whole planet.

What might have seemed, from the vantage point of the middle of the 19th century, exaggerated in the Manifesto, almost a dreamscape, today feels commonplace to us.

Many liberals and conservatives will grant that Marx foresaw what few of his contemporaries did. For instance, the Economist magazine once wrote that Marx’s account of the “survival and prosperity of capitalism has never been bettered”.

Of course, to paraphrase Shakespeare, Marx came not to praise capitalism, but to bury it – which is where he parts company with the good editors at the Economist.

Marx was hardly the first critic of society, though, and he was not even the first communist. Jesus of Nazareth was among the many to condemn “rich men” long before Marx.

What makes Marx unique is that he was the first to propose a historically specific path for winning equality that combined defiance of oppression and exploitation with a social force potentially capable of replacing the elite with an equitable and democratic common association – socialism – as opposed to a new ruling class.

Marx’s insights did not come all at once, but accumulated over time as he tested, revised and fought for his ideas over the course of four decades before his death in 1883. For the purposes of this article (although nothing is ever so simple in real life), I will delineate some of Marx’s conclusions as a series of theoretical leaps.

True to the revitalised dialectical method he took over from the German philosopher Hegel, Marx didn’t completely reject or leave behind his previous positions, but radically reconstructed his understanding of social dynamics, based on new knowledge and, critically, political struggle.

Leap one: from critic to radical democrat

Marx began his studies as a student of philosophy in the still unsteady aftermath of the great French Revolution of 1789, immersed in a highfalutin world dominated by the aforementioned Hegel.

Hegel emphasised conflict and transformation – whether societal, cultural, spiritual and intellectual – as opposed to a world shaped or determined by static or immutable God-given truth or truths.

In the end, Hegel made peace with Germany’s autocracy and retired as sort of academic superstar. But some of his students, aptly named “Young Hegelians”, turned his analytical tools to debunking the Christian hierarchy and probing the limits of Germany’s supposedly liberal monarch.

They placed great faith in their role as critics, but often got lost in ideological battles disassociated from real politics, leading Marx to subtitle an early work “A Critique of Critical Criticism” at their expense. While some clipped their wings in order to not run afoul of the authorities, Marx’s combative disposition led him to conclude that “the weapon of criticism cannot, of course, replace criticism by weapons”.

He landed a job in 1842 as editor of a liberal newspaper called the Rheinische Zeitung (Rhineland Times) and set about journalistically savaging laws that prohibited peasants from collecting firewood on the gentry’s estates and limited freedom of the press.

These conflicts taught Marx that society was not made up of autonomous individuals operating under a more (or less) democratic government. Rather, society was divided into classes and ruled over by a political state.

Marx wielded his pen like a sword, but the Prussian police wielded real swords, shutting down the paper in 1843 and sending Marx into exile.

Leap two: a class with radical chains

If he chafed under the power of the ruling class in the Rhineland, Marx came face to face with a radical working class in Paris while living in exile in the winter of 1843-44. This was a movement that terrified the nobility and had, in 1830, helped bring down a king – even if he was replaced by a different king in the end.

Here was a power that Marx came to believe could overturn society, whereas his radical journalism had proven impotent on its own. Here was “a class with radical chains”, as he wrote.

This already sounds like the stirring conclusion of the Communist Manifesto: “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains”. But Marx was, to put it bluntly, still as much of an elitist as his old critical critic friends, writing in one work: “The head of this emancipation is philosophy, its heart the working class”.

In other words, philosophers would ride the working class to victory. That victory might aim to abolish the privileges of the old ruling class and redistribute the wealth, but who would rule over it? Benevolent (socialist) intellectuals?

Over the next year, Marx became familiar with the lively networks of radical and revolutionary workers in Paris and wrestled with the limits of his own thinking. Rather than “philosophers” as the natural leaders and workers the inevitable followers, Marx came to see that politics arises from social struggle, not detached contemplation, no matter how radical.

Thus: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it”.

This is not only a call to action. Just before writing this famous sentence, Marx noted that “it is essential to educator the educator himself” – thus dethroning intellectuals from a privileged perch over the working class.

Instead of thought preceding change – which is the basis of the idea that “In the beginning there was the word” – Marx concluded that “the coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice”.

Leap three: class struggle and revolution

Marx was still not entirely clear about what this “revolutionary practice” might consist of. It was certainly more than writing books or articles – a political movement was needed. But what kind?

In 1845 and 1846, Marx produced an odd and wonderful work called The German Ideology that contains the core ideas later popularised in the Manifesto. Most important for our purposes here, Marx finally hit upon how workers could overcome the intellectual and material power of the ruling class, while simultaneously dealing with their own shit:

“For the production on a mass scale of this communist consciousness, and for the success of the cause itself, the alteration of men on a mass scale is necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and becomes fitted to found society anew.”

Marx had come a long way from battling fellow graduate students over French novels and philosophical treatises. He now saw that the working class was the only social group potentially powerful enough to defeat the forces of order, and that the working class itself would become conscious of its own goals in a living mass movement, a revolution – not through lectures by well-meaning philosophers.

Marx’s understanding of the “muck” rested heavily on his studies of how capitalist exploitation – that is, spending most of your life at work for someone else – gave rise to what he called alienation and a general depreciation of human spirit and cooperative nature.

This is a tremendously useful insight, but at this point, Marx had only an inkling of how capitalism systematically invented and weaponised what we today might call intersectional oppressions.

For his part, Engels’ experience working in his father’s factory in Manchester afforded him sharper insights into sexism, abuse, addiction, disease and racism. Nonetheless, Marx understood enough about how capitalism infuses workers with division, hatred and self-loathing to identify the “muck” as a powerful internal enemy that could not be taught, preached or wished away. It had to be fought.

Leap four: harder than it looks

Within weeks of the Communist Manifesto’s publication, revolutions broke out across Europe, and Marx and Engels hustled back to Germany to take part.

Marx was not so naïve as to believe that socialism was on the agenda. He knew that capitalism was only taking root in the 1840s and, concurrently, the working class remained a relatively small portion of the population.

But Marx and Engels did expect 1848 to sweep away the remnants of feudal political and social structures, while winning democratic rights for working class movements – which would then ride waves of economic growth toward a showdown with the capitalist bosses, whether in the shorter or longer term.

That was the plan. As it turned out, there were two big problems.

First, the emerging capitalists proved to be timid anti-feudalists who found it easier to compromise with monarchs than to conclude democratic alliances with restive and radical working class movements. (Sound familiar?)

And second, it wasn’t a fair fight. In addition to the “muck of ages” and internal divisions, workers faced a centralised, armed, organised enemy in the ruling class state. So long as this state remained whole, it had the power to suppress or absorb any revolutionary challenge.

As Marx explained in 1852, “All revolutions perfected this machine instead of breaking it. The parties that contended in turn for domination regarded the possession of this huge state edifice as the principal spoils of the victor”.

This problem remained unsolved over the next two decades as Marx continued his practical and theoretical activities, including agitating against the Confederacy in the US Civil War, writing his groundbreaking work Capital and helping to found the so-called International Workingmen’s Association – the first attempt at coordinating international working class movements.

Leap five: taking power for ourselves

In 1871, exhausted by a senseless war between Germany and France, workers and the poor in Paris threw out their capitalist government and replaced it with the Paris Commune. For 71 days, the red flag flew over the most famous city in the world.

The Commune granted universal (male) suffrage and placed trade unions, cooperatives and socialist and anarchist political parties and currents in power. The capitalists and their paid politicians fled the city.

German and French rulers knew the real enemy when they saw it and, putting aside their military conflict, conspired to drown the Commune in blood. Thirty thousand died in the fighting and subsequent mass executions.

In the wake of the fighting, Marx and Engels added a note to the Communist Manifesto, warning that the Paris Commune confirmed that the “working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes”.

Instead, workers and the oppressed must not only break up the old ruling class state machine, as Marx argued after the experience of 1848, but they must create their own – a democratic and revolutionary form of government, like the Commune – in order to win.

Easier said than done. But Marx’s method of incorporating new insights in the best conclusions of previous battles gives us an edge. I would argue, an edge without which we have no chance of winning.

Two hundred years is a long time, at least in the epoch of capitalism.

But Marx would recognise Donald Trump for the reactionary he is, and he would celebrate the teachers’ strike wave in West Virginia and Kentucky and Oklahoma and Arizona. He would recognise the terrible human toll of a system based on profits for the few and misery for the many.

He would recognise that radicals must merge with a living mass movement if they want to challenge the powers that be. And he would recognise Egypt and Occupy and Black Lives Matter and #MeToo and the March for Our Lives.

But he would also insist that the only social force capable of moving from protest to power is the global working class.

----------

First published at www.SocialistWorker.org.