By the end of the 1970s and in to the early 1980s the Cold War was building. It was an intense period. The Ban the Bomb movement had been strong in the 1960s, as had the women’s movement in the 1970s. And then nuclear weapons started to be brought back in a big way.

I remember the Christmas period of 1982. That year, the first mass Greenham Common action had taken place. Greenham Common was very famous in the 1980s. It was a nuclear missile base in England. Women-only camps were set up around the base and lasted for about two decades. This became a source of inspiration for women and the wider peace movement because of the radical direct action involved and the willingness of participants to take on the nuclear power and nuclear armaments industries.

There was a clear understanding at the time – very strong in Australia – that the uranium industry was not separate from the nuclear arms industry. Those involved in the industry and many politicians tried to make out that they were separate, but we worked really hard to show the links.

In the early 1980s, inspired by Greenham Common, women’s peace groups began to form in Australia. In NSW we had Women’s Action Against Global Violence, in Canberra it was Women’s Action for Nuclear Disarmament. We all had different names and formed in different ways, but we had a common recognition of the big task at hand. I learnt a lot of political lessons through this work.

**********

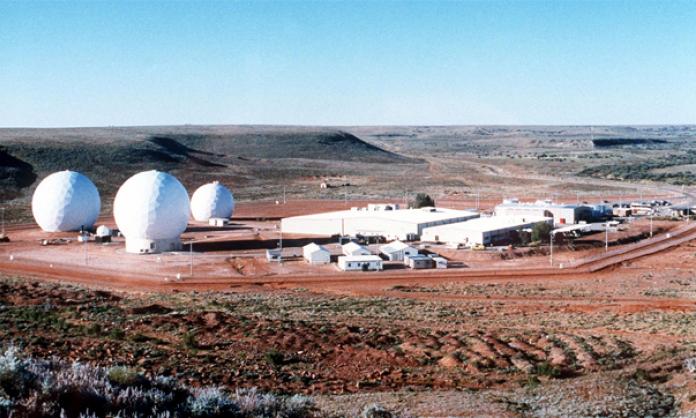

A big meeting was held over Easter in 1983 in Canberra. I was pregnant with my third baby so didn’t get to it, but it was decided there that we were all going to go to Pine Gap. Which, if you don’t know, is a place literally in the centre of Australia. It’s a massive US war and spy base, and it’s very hard to get to.

It was decided to go in November, when it’s extremely hot. I’d organised a lot of things by then, and I remember thinking when I heard of the Canberra decision, “Oh my god, how are we going to pull that off?”. But we pulled it off. It was amazing, between 600 and 800 women got there by plane, car and coach.

People often ask me “How did you do it? You didn't have internet or fax machines, you didn’t have anything. How did you do it?” Well in many ways it was the objective conditions. The fear of nuclear disaster was palpable. I remember breastfeeding late at night and developing a fear of news flashes – and I’m not a very fearful person – but I came to worry when there was a news flash in case it was announcing that nuclear bombs had been dropped and a nuclear war had started. That was what it was like. The threat of nuclear war was real – that’s why we had huge numbers.

In the build-up to the Pine Gap action, we staged what we called die-ins in Sydney. We used a parachute to symbolise a nuclear blast, and women dressed in black would go underneath it and then they would be all contorted as the parachute was pulled away. We would do this in shopping centres, or in Martin Place, and wherever we were, people would stop and be really moved by it. We would give out leaflets at the end. It was a way of getting across to people that the world was under threat, that they were under threat, their future was under threat.

**********

The actions at Pine Gap itself were truly phenomenal. The organising meetings for the day’s events would start at half seven in the morning. Because it was so hot, actions would start early. One of the most spectacular ones was to mark the birthday of Karen Silkwood. Karen worked in the US nuclear industry and became aware of very dangerous practices. She was also a union activist. It’s understood that she was murdered, possibly by the FBI, because she intended to give information to journalists about the industry. Her murder was big news at the time, especially within the progressive movement.

Our campaign started on 11 November, and 13 November was Karen’s birthday. We decided to have a mass action and march on Pine Gap. This is where the women were very courageous. We had found out what laws covered the base – they were special Commonwealth laws which meant you could be fined huge amounts of money and be jailed for a very long time for entering. We had informed everybody about what they might face if they got arrested and what their rights were, and we had legal teams to help.

In the end, 111 women went into Pine Gap that day, led by Aboriginal women. They took down the gate and went in. The next day there was a new gate in place and the women put up a sign saying: “Congratulations boys on your quick erection”. The signs in general were brilliant. When the 111 women were arrested, they all gave their names as Karen Silkwood before being taken into the lockup in Alice Springs.

**********

People often say to me “Well, what did you get out of it? Pine Gap is still there and Women for Survival (the name we came together under for the action) doesn’t exist anymore”. To be frank, the group did cease to exist pretty quickly. We hit this high, and then the next year we had another big action at a base in Western Australia, but within a few months the organisation did not exist.

But it was a lesson for me in terms of what success is when you organise political actions. Many of those women were politicised for the rest of their life. Still today we often introduce ourselves as Pine Gap women. The women involved work in all sorts of areas doing great political work, so the legacy survives in different ways. And the action was successful in terms of politicising people and getting the issue on the agenda.

----------

Edited excerpts from a speech delivered at Marxism 2019 conference, held over Easter 2019. Transcription by Eleanor Morley.