Towns and cities across Sudan were flooded on 30 June with protesters responding to the call for a “millions march”. It was the largest pro-democracy rally since the 3 June massacre in which the notorious Rapid Support Forces – formerly a militia called the Janjaweed, created to wage a genocidal war in Darfur – crushed a months-long sit-in outside the Sudanese military headquarters in the capital, Khartoum.

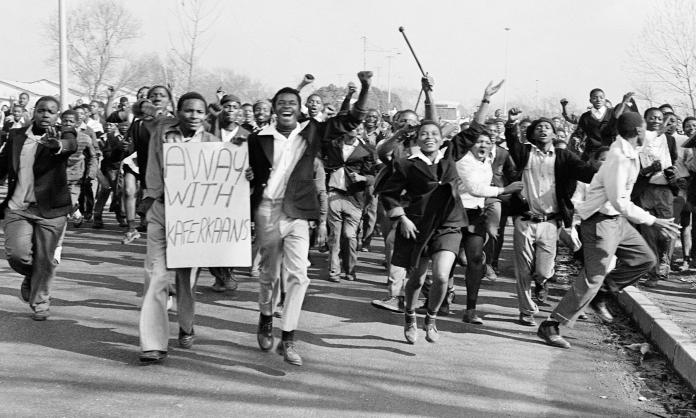

Millions of people from all walks of life once again stared down the barrel of the regime’s guns to demand a democratic transition to civilian rule. In the streets of Khartoum, under military lockdown, they chanted “Madania” – the Arabic word for civilian. They also chanted “Madania” while attempting to cross the White Nile bridge in Sudan’s second largest city, Omdurman, as the Rapid Support Forces opened fire on them. Right across Sudan, they chanted “Selmya” (peaceful) and “Madania”.

The mass protests did not end there. They instead became the impetus for a resurgence of revolutionary activity, protesters engulfing the streets and public places in the days after. The student movement rallied in enormous numbers, and on 4 July high school revolutionary committees in Medani city, 186 kilometres south of Khartoum, led a massive demonstration to the regional Ministry of Education to demand a fully civilian-led government. Students in Sennar City did the same, spurring evening protests in solidarity with the students. All over Sudan these scenes replayed day and night.

Internationally, the Sudanese diaspora and supporters demonstrated their solidarity with the renewed struggle, staging rallies and protests on 30 June. With pressure mounting against the Transitional Military Council, the backbone of a 30-year dictatorship still in power after protesters ousted its leader Omar al-Bashir in April, the leadership of the uprising called for another wave of civil disobedience. The Alliance for Freedom and Change announced, via the Sudanese Professionals Association, plans for a general strike on 14 July, to be preceded by mass protests on 13 July.

No sooner had the ink dried on those plans than a dramatic about-turn took place. On 5 July the leaders of the Alliance for Freedom and Change announced they were entering into a power sharing deal with the military junta. They agreed to establish a joint sovereign council made up of 11 members – five military, five civilian and one “compromise” member. For the first 21 months of the agreement, the military will rule, followed by 18 months of civilian rule, after which there will be elections. That is, if things progress that far.

By any measure, the deal is terrible. It betrays the central, unwavering demand of the revolutionary uprising – to overthrow the regime and transition to a democratic, civilian government. The army generals, the security apparatus and the militias of the Sudanese military state, are the counter-revolution. They have spent months savagely crushing a revolutionary movement for democracy. They could not have been clearer, in both words and deeds, about their opposition to democracy and civilian rule. Yet for nearly two years they will stay in power under this agreement.

What happened to make people who, just days before, had been calling for civil disobedience capitulate to the regime?

Enormous pressure has been exerted by outside forces for a deal that would leave the military in control. The regional forces of counter-revolution and linchpins of reaction – Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – have been key. Both governments have pledged billions of dollars to the Sudanese regime recently and, urged on by Western diplomats eager to see a compromise between protesters and the military, took advantage of fractures within the revolution’s leadership to convince the Transitional Military Council to agree to a power sharing deal.

For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and the Western powers that back them, the crushing of revolutionary uprisings is important for maintaining their own despotic rule. For now, though, they’ve been persuaded to convince the generals in Sudan that a pragmatic deal with a fracturing revolutionary leadership will better facilitate the continuation of their rule.

Liberals in the Alliance for Freedom and Change have tailed the counter-revolutionary generals much more openly in recent months. Members of the Communist Party, some leaders of the Sudanese Professionals Association and many neighbourhood resistance committees have opposed any compromise. Many of them were arrested prior to and during the massive 30 June protests. The power sharing deal was brokered at a moment when the revolutionary masses were re-energised and united around the demand for a civilian government. It was at this moment that the class collaborationist politics of bourgeois liberal forces in the leadership capitulated to the Transitional Military Council, its regional backers and Western intermediaries.

Crucially, there have been ongoing protests rejecting the deal. Localised resistance committees in major towns are leading efforts to organise against the compromise and continue grassroots resistance. Waleed Omar, a resistance committee leader in Omdurman, explains, “We haven’t been consulted and we haven’t been represented so we are against it. We don’t care about these political agreements and these compromises. We are preparing for a new wave of protests and we will show them the will of the nation”.

A translated statement from 7 July from the Alliance of the Resistance Committees of Al-Barrari (Lions of Al Barrari) argued, “The agreement of the dawn of the fifth of July is not the highest aspirations of the Sudanese street, nor that for which lives were sacrificed or for which blood was shed and souls lost. The continuation of the grassroots resistance committees in neighbourhoods and the continuation of the youth movement, organisation and awareness, is the real popular guarantor of the success of the revolution, the valve of its safety and its compass to achieving freedom, peace and justice”.

In Port Sudan, where wharf workers have been leading strikes in the past months, resistance committees issued similar statements. These local organs of power, especially where they involve the organised working class, are key to the continuation and further radicalisation of the revolutionary movement. Their main slogan in the wake of the compromise deal is “Victory or Egypt”, reflecting an understanding of not only the threat of counter-revolution but also the risk that liberals will betray the revolution from within.

The Sudanese revolution faces many challenges. Its enemy is not only a savage military dictatorship desperate to hold on to power, but also a range of wealthy and despotic regional players and their anti-democratic Western partners. This is also why the revolution is so important. Its existence and its success symbolise what is needed from one corner of the globe to another – revolution to overthrow the despots who rule everywhere.