Justin Akers Chacón is a Professor of US History and Chicano studies at San Diego City College and the author of Radicals in the Barrio and No One is Illegal. He is a member of the Coalition to Close the Concentration Camps in the San Diego-Tijuana border region. He spoke to Red Flag’s Nahui Ludekens.

----------

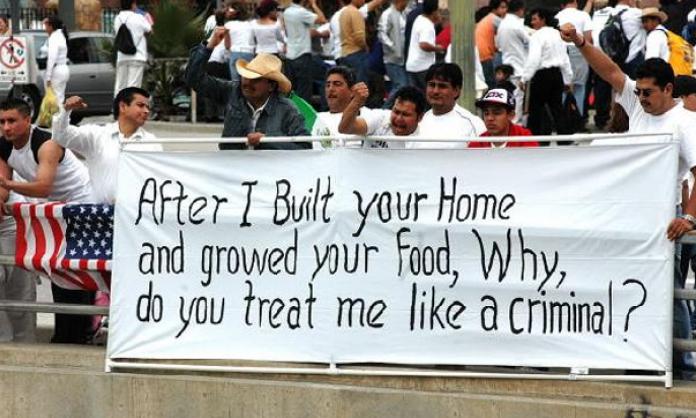

“Nosotros no cruzamos la frontera, ésta nos cruzó a nosotros” (“We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us”) is a slogan that is enjoying a revival today in the movements against Trump’s border policies. Where does it come from?

I first heard that slogan in the immigrant rights movement in 2005–06, at a time when we began to see large rallies primarily led by working class people: Mexicans, Central Americans, but also Caribbean people. It reflects something embedded in the popular memory: that much of the south-west of the US used to be part of Mexico. That land was taken by force through war, which led to the borders literally being redrawn around thousands of Mexicans. I would say that this popular memory is deeply woven into Mexican national consciousness as part of a broader understanding of the role of US imperialism in Mexican history.

When people are forced to migrate to find work, especially when they cross national borders, they become more aware that there are no national borders for capital. So it’s also like they are saying that the borders of capital crossed us, even if it’s not expressly stated that way. The slogan kind of embeds these ideas and an understanding of the forces at work.

How did Mexican-American migrants help develop the American left and the first struggles for civil rights?

Firstly, it’s important to appreciate that Mexicans across the border entered into the ranks of the US working class – as railroad workers, as miners, as agricultural workers – with a rich tradition of radical organising stemming from their experience of the Mexican revolution.

By the 1930s, we begin to see the rise of the Communist Party (CP) in the US. For all of its contradictions, it embraces the orientation that Black communities and Mexican communities needed to be organised as part of the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movement.

This orientation allows Mexican migrants and people from Black communities to organise together. Some of the first great battles for civil rights take place in these communities in the 1930s. The 1960s are almost always characterised as the beginning of the civil rights movement, but they were really the second wave of struggles that originated in the 1930s – struggles that began with working class people.

Another element that’s important to understand is that by the late 1930s the CP had played a significant role in organising the Congress of Industrial Organisations (CIO), which was the industrial movement that developed out of the American Federation of Labor. In 1937 the CIO was expelled from the federation, so it began to form its own unions. The CIO unions had an anti-racist orientation and begin to organise migrant workers.

In Texas, the convergence of the CP, the Mexican community and the CIO saw the formation of the agricultural workers unions that organised pecan shellers – who were primarily women – into the first agricultural industrial union.

Mexican communists were then able to marshal the power of that industrial movement to help support fights against racial segregation and for housing rights. Through the convergence of these campaigns we see the start of the fight against racial oppression and segregation in barrios across the country. Here in San Diego, for example, the CP, CIO and Latino radicals organised against KKK violence against migrants on the border.

Luisa Moreno was an important working class radical in the civil rights movement. Can you tell us more about her?

Luisa Moreno was a Guatemalan woman who started off as a garment worker in New York. Through this work she came into contact with Puerto Rican socialists. Her introduction to socialist ideas was through the garment factory at which she worked, which was organised by the CP.

She played a key role in organising an agricultural workers union, the United Cannery Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America, which became one of the largest unions in the US. It organised some farm workers but mostly packing and cannery workers.

My great-grandmother worked in a citrus packing plant bagging citrus fruits and putting them in boxes. A lot of women worked in these sorts of industries. Their union became a very interesting one. At its height, it represented more than one million people and organised primarily Mexican and African-American women in the South. It was one of the most radical unions because it advocated for some of the first contracts that abolished pay differentials between white, black and Mexican workers. It also won some of the first contracts that abolished pay differentials between men and women. They had conditions like paid childcare and maternity leave written in contracts, and this was in the late 1930s to 1950s! It was one of the first unions to push to have all employee materials in Spanish and English, including the contracts, so the workers could read them during the negotiations. This is where a lot of the civil rights activism really begins.

Luisa Moreno was instrumental as a leading force and was one of the first radicals and thinkers who understood how immigration policies and borders were used to divide workers based on nationality. She argued for the unions to organise against immigration restrictions and organise undocumented workers. Moreno was central to organising the first national civil rights campaign movement for Latinos in the US, called the Spanish-Speaking People’s Congress. They were able to build chapters around the country linked to the CIO locals. They also did organising work in the barrios: everything from rent control to racist policing. They were the first forces in the US to argue for what we call “ethnic studies education”. They advocated for this in the early 1930s and 1940s, so this is really the foundation of the civil rights movements coming directly from working class people and starting that historic process.

How have attitudes to immigration policies and national divisions in the working class movement changed from Luisa Moreno’s day?

Our immigration and border policies grow out of patterns of capitalist accumulation. The specificities change according to the needs of US capitalism. This helps to explain why they change and even become contradictory at times.

The specific experience of Mexican migrants is a useful starting point from which to better understand these patterns. As I argue in my first book, No One is Illegal, the Mexican working class is the “other US working class” because of its significance at every stage of US modern development, from the second half of the nineteenth century to today.

Look at the border infrastructure itself: in 1924 the border patrol is created. This is a time when there’s a large number of migrant workers in the US south-west, working predominantly in mines, agriculture and railroads. The job of the border patrol is to regulate the migrant population, specifically by deporting unemployed workers, which is why its creation coincides with the criminalisation of Mexicans in the US. This makes it easier for the capitalists to carry out their deliberate process of staggering agricultural production as much as possible in order to move labour from region to region to harvest the crops, and then forcibly move them out in the off season.

In this way, the immigration enforcement system develops according to the needs of capital and the capitalists’ desire for an exploitable workforce. The border patrol takes on a dual function: to both regulate labour and target workers when they try to form unions or speak up for their rights. At every phase of capitalist development in the US since the late 1800s, the immigration system in large part has been shaped by the dependence on Mexican labour and the desire to better exploit it. Now we see how that machinery is being used and expanded against Central American workers.

In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act made it illegal to hire undocumented migrants. This led to discrimination against workers who appeared foreign, resulting in greater unemployment for undocumented workers. It wasn’t until the 2000s that the CIO officially took a position of supporting the right to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and joined unions challenging the AFL, which had a very “old, white craft union” mentality. This only happened because communists and socialists argued for it within the labour movement and because so much of the working class are people of colour and immigrants.

The reason why this is so central to understanding the class dimensions of US society is because every major victory for the union movement in this country, every period of growth and expansion, has come when the union movement incorporated people of colour and immigrants, and when it has been led by immigrants who challenge the rest of the labour movement.

Immigrant repression is the repression of unions. It’s a direct class war. Unfortunately, the labour movement has largely withdrawn from the fight on this issue, even if they haven’t changed their official position.

Their withdrawal from the fight, and the open class attack on the immigrant working class, means a weakening and decline of the union movement as a whole. Immigrants are not declassed or some kind of marginal force. They are at the centre of the working class, and the future of the migrant workforce is the future of the union movement.